According to Oregon rancher, Keith Nantz, here’s what most people don’t understand: The Obama Administration has pushed the Western ranching industry to the brink. The Ammon Bundy-led seizure of a federal wildlife refuge thrust Oregon’s ranchers into the spotlight. Being a rancher was always challenging. And it has become increasingly difficult under the Obama administration.

Most of the time, those regulations are written by people with no agriculture experience, and little understanding of what it takes to produce our nation’s food. . . These decisions are being made by people who are four to five generations removed from food production.

My name is Keith Nantz. I’m an Oregon rancher. I grew up in a ranching community in northeast Oregon. Even as a kid, I knew I wanted to be a rancher. After eight years as a firefighter, I’d saved enough to start my own business. I wanted to work on the land, raising delicious, wholesome beef for our growing population.

My name is Keith Nantz. I’m an Oregon rancher. I grew up in a ranching community in northeast Oregon. Even as a kid, I knew I wanted to be a rancher. After eight years as a firefighter, I’d saved enough to start my own business. I wanted to work on the land, raising delicious, wholesome beef for our growing population.

For almost a decade, I’ve done just that. Most days, I’m up before the sun rises. I spend my mornings tending to my horses, dogs and livestock. In the winter, when it’s bitter cold, I’m outside with my cattle, making sure their water isn’t frozen and that they’re properly fed. In the summer, I often work 15-hour days, cultivating my crops and tending to the animals. In the afternoons, I’m in my office, reaching out to customers and handling the ranch’s business side. Over the course of a given day, I act as a vet, a mechanic, an agronomist and accountant.

I love the work, but it’s grueling. As a rancher, I’m always one bad year away from financial disaster. Every purchase I make — from new cows ($2,000 each) to a new piece of equipment worth hundreds of thousands of dollars — is a major investment. And my ranch operates on very slim margins, so I have to be savvy to make ends meet.

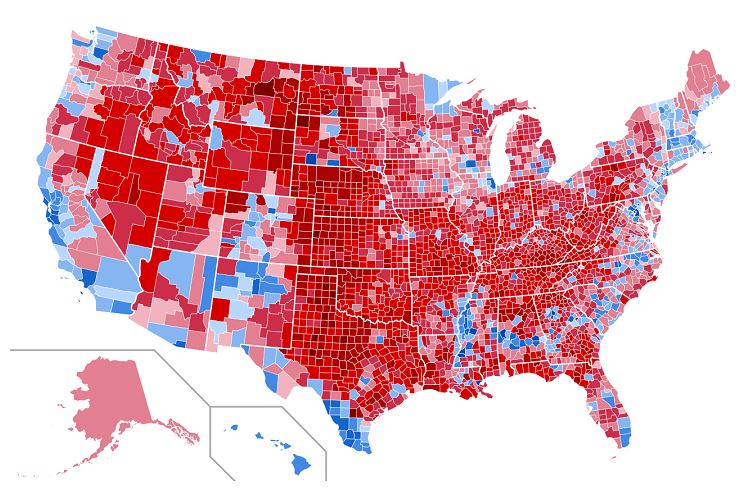

Money isn’t the only challenge. Raising cattle requires a lot of land, much more than most ranchers can afford to own outright. I lease about a third of the space I use from private owners. But most ranchers aren’t so lucky. The federal government controls a huge amount of land in the west (more than 50 percent in some states, like Oregon), and many ranchers must [utilize] that space to create a sustainable operation.

The Ammon Bundy-led seizure of a federal wildlife refuge thrust Oregon’s ranchers into the spotlight. While I don’t agree with the occupiers’ tactics, I sympathize with their position. Being a rancher was always challenging. And it has become increasingly difficult under the Obama administration.

Utilizing federal land requires ranchers to follow an unfair, complicated and constantly evolving set of rules. For example, a federal government agency might decide that it wants to limit the number of days a rancher can graze their cattle to protect a certain endangered plant or animal species, or they might unilaterally decide that ranchers can’t use as much water as they need because of a fight over water rights. Or they might take over land that once belonged to the state or private individuals, imposing an entirely new set of restrictions.

I saw this play out firsthand when the federal government considered listing the sage grouse, a chicken-like bird, as endangered. That regulation would have shrunk the amount of land where ranchers could graze cattle, putting many out of business and decimating the industry. To avoid this, ranchers like myself and local officials spent months meeting with federal officials looking for compromise. We ultimately found [some degree of] middle ground. But we already have an enormous workload in our daily lives. The pressure of having to drop everything to lobby against a rule (which happens more often than you’d think) is a tremendous burden.

Most of the time, those regulations are written by people with no agriculture experience, and little understanding of what it takes to produce our nation’s food. The agencies that control these lands can add burdensome regulations at any time. Often, they will begin aggressively enforcing them before ranchers have a chance to adjust.

This forces us to either find new grazing land, reduce the size of our herd or sell out completely. In rural communities, this can have a catastrophic effect on the local economy and environment. Ranching is a billion-dollar industry in Oregon. Overall, agriculture accounts for 15 percent of the state’s economic activity and 12 percent of the state’s employment. The income of a local farm generates double the money for the local economy as a supermarket’s income in the same area, according to the London-based New Economics Foundation.

This forces us to either find new grazing land, reduce the size of our herd or sell out completely. In rural communities, this can have a catastrophic effect on the local economy and environment. Ranching is a billion-dollar industry in Oregon. Overall, agriculture accounts for 15 percent of the state’s economic activity and 12 percent of the state’s employment. The income of a local farm generates double the money for the local economy as a supermarket’s income in the same area, according to the London-based New Economics Foundation.

The siege on our industry has only increased under the Obama administration. Officials are effectively regulating us out of business by enforcing a string of unprecedented environmental restrictions. In Malhuer county (next to Harney county, where the current standoff is taking place), the Obama administration is considering a measure that will turn 2.5 million acres of federal land into a “national monument,” a move that would severely restrict grazing. These restrictions would cause a huge economic downturn for those communities.

These decisions are being made by people who are four to five generations removed from food production. The rule-makers don’t quite understand our industry, and are being spurred on by extreme environmentalist groups asking for unreasonable policy changes.

It’s not that I don’t care what the environmental community wants. In every part of my business, I try to find a balance between economics, mother nature and our culture. I know that if we don’t treat our land properly, we will go out of business by our own hands. It is of utmost importance for us to be true conservationists if we want to continue producing the most nutritious and safest protein in the world.

But all too often, I’m not given the autonomy to do so. I’m given rules, not a conversation about how ranchers and government officials and environmentalists might be able to work together. That’s an approach that fails everyone.

Keith Nantz is ranch manager at Dillon Land and Cattle in Maupin, Ore.

RANGE / RANGEFIRE! — Addressing Issues Facing the West / Spreading America’s Cowboy Spirit Beyond the Outback