(An excerpt from one Chapter of Todd Macfarlane’s Memoir Manuscript, Making Rain Where the Sun Shines — Lawyers are Supposed to be Golfers — Paying My Dues as a Country Lawyer, written in 2000 under the pen name Mancos MacLeod (names were changed throughout the manuscript to protect the innocent, . . . or guilty, as the case may be), about real events that happened in 1992 — well before Macfarlane ultimately ended up settling in Kanosh. SEE The Sound of Freedom — Why We Moved to Millard County. This account describes just the first of 25 years worth of experience in the trenches of Western water wars, ultimately including Pole Canyon and the Central Utah Water Project — the primary reason Todd was recruited to participate in Pole Canyon was based on thorny water issues, and Todd’s extensive experience in water fights).

As the undeniable lifeblood of Southern Utah, and perpetual bone of contention, almost right from the outset, I got the chance to make a lot of rain out of water.

As the undeniable lifeblood of Southern Utah, and perpetual bone of contention, almost right from the outset, I got the chance to make a lot of rain out of water.

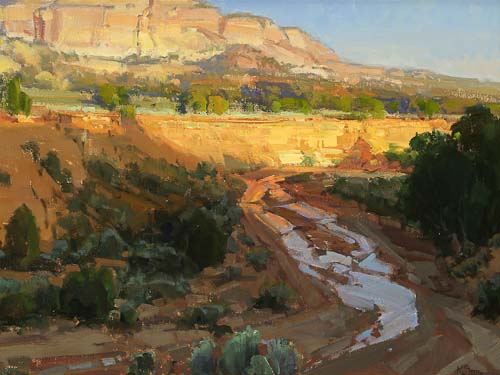

Like most communities and civilization in Southern Utah, the settlement of Kanab coincided with proximity to water. Kanab Creek, which runs along what had once been the western boundary of a small frontier outpost, on the edge of the wild Arizona Strip country, provided a water source for early settlers to dip drinking water, and divert larger amounts for irrigation. In fact the town’s name, like many place names in the area, comes from the Southern Paiute Indian word for “willow,” or place of the willow, which in this area, invariably grow around water, and in Kanab’s case, grew in abundance along the creek.

When it was first settled, Kanab was at the outer reaches of Mormon Zion, almost completely isolated by distance and geography from most of the rest of the kingdom. Despite or perhaps because of its isolation, however, it had to serve as the commercial hub for a vast area of largely uninhabited country, clear to the Colorado River. Consequently, almost from the outset, Kanab became a bustling little cow town, just inside the Utah state line. Its quieter Arizona counterpart, Fredonia, was also located along the banks of Kanab Creek, just south of the border. Kanab and Fredonia were the last two vestiges of civilization before entering the vast Arizona Strip, a massive chunk of land connected to Arizona only by arbitrary political boundaries, but physically separated by the Grand Canyon, one of the greatest natural barriers on Earth.

When it was first settled, Kanab was at the outer reaches of Mormon Zion, almost completely isolated by distance and geography from most of the rest of the kingdom. Despite or perhaps because of its isolation, however, it had to serve as the commercial hub for a vast area of largely uninhabited country, clear to the Colorado River. Consequently, almost from the outset, Kanab became a bustling little cow town, just inside the Utah state line. Its quieter Arizona counterpart, Fredonia, was also located along the banks of Kanab Creek, just south of the border. Kanab and Fredonia were the last two vestiges of civilization before entering the vast Arizona Strip, a massive chunk of land connected to Arizona only by arbitrary political boundaries, but physically separated by the Grand Canyon, one of the greatest natural barriers on Earth.

The Arizona Strip is some five million acres of ancient forests, high desert and deep canyons, with virtually no live water; which because of the lack of water, essentially remains a vast, uninhabited frontier, clear to this day. Remarkably (particularly when supported by favorable weather patterns), the Arizona Strip had, at one time, been home for a handful of thrifty settlers, and a thriving, far-flung natural resource and production-based economy. Yet today, over a hundred years later, despite a number of scattered ranching operations, the Strip has no surviving interior communities and very little settlement, except around the edges.

Although Kanab and Fredonia, at one time almost twin communities along the creek just across the border from each other on the Utah/Arizona state line, have always been quite similar in some ways, in other ways, there is and always has been at least one very critical difference. In an arid region whose growth and development is completely dependent upon very limited water resources, Fredonia has always been the underdog, forced, according to a crude, but apropos expression in the local vernacular (with minor revisions), to “suck the hind quarter,” so to speak, of what little “Utah” water finds its way across the border, after Kanab and other upstream users had their fill. Because it had essentially no in-state water resources, even the vast majority of Fredonia’s limited culinary water supply at the time came from springs in Utah.

* * * * * *

By the time I arrived in 1991, the glory days of Kanab’s greatest claim to fame — the Western movie industry  — had long since faded. For a time, Kanab was dubbed, and undoubtedly deserved the title: Little Hollywood. A number of great classical westerns, including How the West was Won, Stagecoach, Fort Apache, and many John Wayne movies were filmed in and around Kanab. In fact, the old Gunsmoke movie set still stood in Johnson Canyon, and the “Paria” movie set stood for many years, before being dismantled, to be restored and partially reassembled at the site. With its mild climate and classic western scenery, as long as westerns were popular, Kanab was a movie-making hot spot. When the western movie market shriveled, so did Little Hollywood.

— had long since faded. For a time, Kanab was dubbed, and undoubtedly deserved the title: Little Hollywood. A number of great classical westerns, including How the West was Won, Stagecoach, Fort Apache, and many John Wayne movies were filmed in and around Kanab. In fact, the old Gunsmoke movie set still stood in Johnson Canyon, and the “Paria” movie set stood for many years, before being dismantled, to be restored and partially reassembled at the site. With its mild climate and classic western scenery, as long as westerns were popular, Kanab was a movie-making hot spot. When the western movie market shriveled, so did Little Hollywood.

Whatever Kanab had or hadn’t ever been at one time, by the time I arrived to tackle the world, there were only remnants of the magical glory days of the movie industry, and it seemed like all the natural resource and production-based industries, including ranching, logging and mining were destined to follow the same demise. By then, the economy was starting to make a strong shift from production to service, and the main industry had become tourism. Despite it’s own inherent natural beauty, however, Kanab, all by itself, apparently didn’t have quite enough pizzaz to attract all the tourists necessary to support an entire economy, but it did serve as a great stop-over for tourists visiting the surrounding national parks. On Summer evenings you could walk downtown, along Kanab’s bustling center street, and hardly ever hear English spoken. Camera toting tourists, clad in shorts and sandals, would be jabbering almost every language found around the globe, but mostly French, German, Italian, Japanese and Korean (depending primarily on whose currency exchange rate was strongest against the U.S. Dollar at the time).

Along with Kanab’s historic isolation, loss of the once thriving western movie industry, and increasing environmental pressures and regulation that seemed to threaten (and eventually kill) virtually all natural resource-based industry; in high, dry, desert country, one of the single most limiting factors in Kane County’s future was its water supply. Nothing, including jibberish jabbering foreign tourists, could survive and thrive without it.

Despite having historically followed the typical boom/bust cycles of the West, many of Kane County’s finest citizens were still convinced that all the permanent, long-term growth, development and prosperity, that had historically eluded Kanab, were finally just around the corner. Although Kanab Creek’s simple existence and proximity had been sufficient to build a thrifty little pioneer settlement around, it wasn’t even close to adequate for a thriving, and hopefully technologically advanced, cosmopolitan metropolis whose economy was quickly shifting to tourism, recreation and residential retirement, to provide a long-term economic toe-hold in the “new economy” of the 21st Century.

Consequently, for quite some time, doing something about Kane County’s limited water resources had me burning the candle at both ends. One of those early mornings, about 6:30 a.m. I’d already been at the office for about an hour and a half, working on correspondence and going over paperwork, when I heard the outside office door open and close. It seemed pretty unusual for that time of morning. Then Orrin Patterson’s head popped around the corner into my door frame. “Looks like you must be a morning person too,” he said, standing there in running clothes, with sweat streaming down his face, as he walked over and plopped down in one of my client chairs.

“Yeah, sometimes things get so crazy during the day that I have a hard time getting much done. It seems like if I really want to get anything accomplished, this is the best time of day to do it; sometimes it seems like the day just goes down hill after 8:00 a.m.”

“If that isn’t the truth,” he said. “So it sounds like you’ve got plenty of work.”

“Yeah, it’s actually been pretty crazy, but we do at least have plenty to do.”

“Well that’s a good sign; better that than the other way around; you must be doing a good job.”

“I’d like to hope so,” I said.

Orrin, a well-seasoned attorney from Delta, Utah, with the law firm of Fatheringham & Patterson, was in town for a court hearing to create the Kane County Water Conservancy District, a project we’d been working on together for about a year. Anyone who had anything to do with water and water law in Southern Utah had heard of Orrin’s partner, Thurl Fatheringham (arguably second only to Ed Clyde in Utah water law circles), made famous, and reputedly very wealthy, by the original IPP (Intermountain Power Project) water deals in Millard County.

I first met Thurl at a water meeting about six months after arriving in Kanab. Several months earlier, almost on the eve of my arrival, Tom Robinson invited me to go to a meeting. At the time, Tom was the principal of Kanab Elementary School (and later Kane County School District Superintendent), a week-end farmer/rancher, and president of the Kanab Irrigation Company. I had just started to get to know him and we were becoming friends. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss long-term water planning in Millard County. Because water law was something I had quite a bit of interest in, and Tom thought maybe they could use a local attorney to help out in the process, I agreed to go. I came to wonder what I had gotten myself into.

At the conclusion of the meeting the ad hoc group elected Tom Robinson to chair a task force to create a county-wide water conservancy district. Tom said that he wouldn’t feel comfortable doing it unless I would be willing to serve as co-chair. By the time we left the meeting an ad hoc Kane County Water Conservancy Task Force had been set-up for the purpose of organizing a county-wide water conservancy district, and Tom and I had been appointed co-chairmen of the task force.

The main concern(s) at the time centered around protecting Kane County’s limited water resources against increasing claims by very demanding out-of-state, downstream water users like Las Vegas and Los Angeles, and even in-state downstream users like St. George and Delta.

In that respect, Utah’s “first in time and first in right, use it or lose it” water policies simply reflected the practical reality of water use in the West. If Kanab, Kane County, or even the State of Utah, for that matter, didn’t use every drop of water available, someone else would, all based on the priority system of first in time, first in right. And once they started using it and became dependent upon it, or even if they didn’t, but had more resources and political clout to fight over it, even despite increasing future needs and demands of upstream users where the water originated, it could get really contentious, and senior priority would be the tool for sorting it all out. Delta itself was a good case in point.

In that respect, Utah’s “first in time and first in right, use it or lose it” water policies simply reflected the practical reality of water use in the West. If Kanab, Kane County, or even the State of Utah, for that matter, didn’t use every drop of water available, someone else would, all based on the priority system of first in time, first in right. And once they started using it and became dependent upon it, or even if they didn’t, but had more resources and political clout to fight over it, even despite increasing future needs and demands of upstream users where the water originated, it could get really contentious, and senior priority would be the tool for sorting it all out. Delta itself was a good case in point.

Looking at a map, Delta, Utah, 200 miles to the northwest, would appear to be an unlikely downstream user, especially from the vantage point of Kane County, but the geographic reality is that a big chunk of South/Central Utah is geographically part of the Great Basin, and the vast majority of water in Southwestern Utah runs north, in the Sevier River, to Delta, leaving much of Southern Utah, particularly including Cedar City and Iron County, high and dry (because the vast majority of water on Cedar Mountain runs off the east side, into the Sevier River).

The determining factor as to whether a specific piece of country is in the Great Basin or not is where it’s water flows. If it flows into the basin, instead of out and ultimately to the ocean, then regardless of other factors like location, proximity, or how it may look on a map, it’s part of the Great Basin. Kane and Garfield Counties sit right astraddle the shoulder dividing the Great Basin from the Colorado Plateau. Some of the streams in both counties are tributaries to the Sevier River, flowing “into” the Basin, while others, like the Escalante, Paria and Virgin Rivers, along with Kanab Creek, are tributary to the Colorado River, which obviously flows “out,” ultimately to the Pacific Ocean.

The determining factor as to whether a specific piece of country is in the Great Basin or not is where it’s water flows. If it flows into the basin, instead of out and ultimately to the ocean, then regardless of other factors like location, proximity, or how it may look on a map, it’s part of the Great Basin. Kane and Garfield Counties sit right astraddle the shoulder dividing the Great Basin from the Colorado Plateau. Some of the streams in both counties are tributaries to the Sevier River, flowing “into” the Basin, while others, like the Escalante, Paria and Virgin Rivers, along with Kanab Creek, are tributary to the Colorado River, which obviously flows “out,” ultimately to the Pacific Ocean.

There must have been something sinister about the way the bottom of ancient Lake Bonneville was shaped, forming essentially the entirety of Utah’s portion of the Great Basin, that in turn shaped the modern landscape to create a drainage like the Sevier River that essentially steals water from Iron, Kane, Garfield, Piute, Sevier and Sanpete Counties and delivers it like manna from Heaven, to Delta, a small but vibrant farming community, located right on the outskirts of Utah’s West Desert.

There must have been something sinister about the way the bottom of ancient Lake Bonneville was shaped, forming essentially the entirety of Utah’s portion of the Great Basin, that in turn shaped the modern landscape to create a drainage like the Sevier River that essentially steals water from Iron, Kane, Garfield, Piute, Sevier and Sanpete Counties and delivers it like manna from Heaven, to Delta, a small but vibrant farming community, located right on the outskirts of Utah’s West Desert.

Delta received its name from the broad, fertile, Sevier River Delta, where apparently centuries of rich sediment had been deposited, leaving thousands of acres of prime farm land, before the river sank helplessly and uselessly into the dry, alkaline pit now known as (Dry) Sevier Lake, which was obviously one of the lowest spots in ancient Lake Bonneville, considerably farther south of the present Great Salt Lake. Talk about an instance of mother nature robbing from the rich and giving to the poor.

I had invited Thurl, and his law partners, Orrin, and his son Robert to come to the meeting and explain the benefits, process and ramifications of creating a county-wide water conservancy district, and talk about hiring them to help us set one up.

With all due respect to Thurl Fatheringham and crew, their presence to talk about water protection and conservation in “upstream” Kane County, epitomized the mercenary, hired-gun nature of the modern legal profession. For many years, first Thurl and then his colleagues, including Orrin and Robert, had been making a very good living practicing law in backwater Delta, primarily by protecting Sevier River water rights against threats and possible encroachments from upstream on the river.

Although that part of Millard County was settled much later than many of the upstream communities, somehow Delta got a jump on a majority of the water rights in the river. Under Utah’s “first in time, first in right” water policy, Delta apparently was either the first to divert and/or make filings to use a majority of the water, which, despite later, increasing needs and demands of upstream users, prevented them from taking water until Delta’s share had been satisfied. Then Delta went to work on storage, acquiring prime reservoir sites, and becoming the moving force in developing a series of large storage reservoirs along the river. Consequently, until only recent years, when agriculture has started slipping as the main industrial and cultural mainstay in south/central Utah, giving way to tourism, recreation, development and other lighter-weight, service industries as the new foundation for the local economy, as kingpin on the river, Delta had been a hiss and a by-word among water users all along the Sevier River Drainage for many years.

Although that part of Millard County was settled much later than many of the upstream communities, somehow Delta got a jump on a majority of the water rights in the river. Under Utah’s “first in time, first in right” water policy, Delta apparently was either the first to divert and/or make filings to use a majority of the water, which, despite later, increasing needs and demands of upstream users, prevented them from taking water until Delta’s share had been satisfied. Then Delta went to work on storage, acquiring prime reservoir sites, and becoming the moving force in developing a series of large storage reservoirs along the river. Consequently, until only recent years, when agriculture has started slipping as the main industrial and cultural mainstay in south/central Utah, giving way to tourism, recreation, development and other lighter-weight, service industries as the new foundation for the local economy, as kingpin on the river, Delta had been a hiss and a by-word among water users all along the Sevier River Drainage for many years.

It is a well-known truth that in a desert water can cause contention. Because of this well-known reality, Mark Twain once quipped, “Whiskey’s for drinking; water’s for fighting.” It is also well known that although Delta is at the end of the stream on the Sevier River, it has long been known as both a tyrant and a bully. Consequently, Delta has long enjoyed a healthy dislike by almost all upstream users and communities. Having spent most of my life in the Sevier River Basin, I had been well-aware of these realities from the time I was a fairly young kid, simply from listening to area farmers and ranchers talk about water.

It is a well-known truth that in a desert water can cause contention. Because of this well-known reality, Mark Twain once quipped, “Whiskey’s for drinking; water’s for fighting.” It is also well known that although Delta is at the end of the stream on the Sevier River, it has long been known as both a tyrant and a bully. Consequently, Delta has long enjoyed a healthy dislike by almost all upstream users and communities. Having spent most of my life in the Sevier River Basin, I had been well-aware of these realities from the time I was a fairly young kid, simply from listening to area farmers and ranchers talk about water.

That may help explain everyone else’s apparent attitude toward Delta, but what I could never quite understand was the deep divisions and well-known bitter in-county rivalry between east and west Millard County — Fillmore and Delta — because the Fillmore area, which is typically referred to by locals as the “East” side, is not included in the main Sevier River drainage. In-county rivalries are not uncommon in Utah — especially in high school sports. When I was growing up, there was a big rivalry between North and South Sanpete (Manti). But I’m not really aware of any other such in-county rivalries that extended much beyond high school sports. Not so in Millard County. In Millard the deep division and rivalry permeates everything.

But, if I were to guess, at this point I would say the ongoing animosity and conflict have little direct connection to water. Unlike everyone else in the Sevier River Drainage, Delta and Fillmore don’t even really compete for the same water. So, water doesn’t seem to quite explain why Delta has always looked down its nose at Fillmore,and treated the East Side as second class, bastard cousins. And likewise, the so-called East Side has historically disliked Delta just as much as everyone else in the Sevier River Drainage. Just plain old jealousy, I suppose. At this point, I would say the top three reasons for ongoing conflict are money, political power, and control. And of course those three all tie together. With all that water, and seemingly a more progressive, “can-do” attitude from the beginning, Delta became more prosperous — especially after IPP (Intermountain Power Project) moved in, and with water came money and with more money came more and more political power. And there’s always that age-old, natural propensity to exercise dominion and control wherever possible. It is no secret that the Delta area enjoys a more vibrant economy and tax base than the Fillmore area. No doubt both IPP and a lot more water have something to do with that. It’s not necessarily Delta’s fault. It’s just the way it is, and often the natural progression of things under such circumstances. From what I understand, however, it was long before IPP even arrived that Delta and the so-called “West-Side” began viewing and treating Fillmore and the “East-Side” as distinctly second class. Growing up in the 1970s I had good friends from the Millard County West side, including at least one friend who was a generation older than me, who said it had been that way as long as they could remember.

But, if I were to guess, at this point I would say the ongoing animosity and conflict have little direct connection to water. Unlike everyone else in the Sevier River Drainage, Delta and Fillmore don’t even really compete for the same water. So, water doesn’t seem to quite explain why Delta has always looked down its nose at Fillmore,and treated the East Side as second class, bastard cousins. And likewise, the so-called East Side has historically disliked Delta just as much as everyone else in the Sevier River Drainage. Just plain old jealousy, I suppose. At this point, I would say the top three reasons for ongoing conflict are money, political power, and control. And of course those three all tie together. With all that water, and seemingly a more progressive, “can-do” attitude from the beginning, Delta became more prosperous — especially after IPP (Intermountain Power Project) moved in, and with water came money and with more money came more and more political power. And there’s always that age-old, natural propensity to exercise dominion and control wherever possible. It is no secret that the Delta area enjoys a more vibrant economy and tax base than the Fillmore area. No doubt both IPP and a lot more water have something to do with that. It’s not necessarily Delta’s fault. It’s just the way it is, and often the natural progression of things under such circumstances. From what I understand, however, it was long before IPP even arrived that Delta and the so-called “West-Side” began viewing and treating Fillmore and the “East-Side” as distinctly second class. Growing up in the 1970s I had good friends from the Millard County West side, including at least one friend who was a generation older than me, who said it had been that way as long as they could remember.

Given the track record and realities in the Sevier River Drainage, it seemed a little bit ironic to have Fatheringham & Patterson telling us how to protect Kane County’s water and water rights from downstream users. Obviously, they knew their business very well, but it was a bit like having the fox guard the henhouse (Kane County was probably about the only upstream county where they could have gotten away with it, and if Kane County had had any bigger stake or interest in the Sevier River, it probably never would have happened even there).

Given the track record and realities in the Sevier River Drainage, it seemed a little bit ironic to have Fatheringham & Patterson telling us how to protect Kane County’s water and water rights from downstream users. Obviously, they knew their business very well, but it was a bit like having the fox guard the henhouse (Kane County was probably about the only upstream county where they could have gotten away with it, and if Kane County had had any bigger stake or interest in the Sevier River, it probably never would have happened even there).

In Southwest Utah, the Virgin River, although just a trickle compared to the Sevier River, with its various tributaries, is the only significant stream that runs south, keeping some water in the southwest corner of the state, watering part of Kane County, and essentially all of Washington County, before terminating into the Colorado River at Lake Meade. Both the East Fork and the North Fork of the Virgin River originate in Kane County.

In the Virgin River Drainage, however, St. George occupies a role somewhat similar to Delta in the Sevier River Drainage: it gets most of the water. But there are several variations of an old saying in the water business that apply to Kane County. The version which I first heard recited by Merrill Heaton, a rancher from Alton, was that “it’s better to be the lowliest deacon at the head of the ditch (which both Alton and Kane County, respectively, were), than to be the loftiest high priest at the end of the ditch.” I heard the other version, which really seemed to hit the proverbial nail on the head, from another prominent farmer in Southern Utah: “a simple stealing right at the head of the ditch can be more valuable than a full water right at the end of the ditch.”

In any event, although the actual amount of water involved is fairly insignificant, Kane County occupies a position at the head of the ditch in both the Sevier and Virgin River Drainages, as well as Kanab Creek (which has only local significance), and was finally in the process of deciding that it was time to do something about it.

Still, even though I and my law office staff would be doing most of the leg work, hiring more experienced heavy-hitters like Fatheringham & Patterson, to help-out and oversee the process seemed like a good idea to me. But there was only one catch. Nobody, including Fatheringham & Patterson, and myself, would get paid anything until the district was finally established and actually got some revenue to pay its bills. And even then, in the spirit of public service, I had agreed to donate 50% of the value of any time I spent on the project, on a pro bono (free) basis. While Fatheringham & Patterson could command over $120/hour for their time, my standard billing rate, starting out at that time, was $80/hour. That meant the district was getting my time for about $40/hour. It seemed like an obvious bargain for the county, by any standard.

Still, even though I and my law office staff would be doing most of the leg work, hiring more experienced heavy-hitters like Fatheringham & Patterson, to help-out and oversee the process seemed like a good idea to me. But there was only one catch. Nobody, including Fatheringham & Patterson, and myself, would get paid anything until the district was finally established and actually got some revenue to pay its bills. And even then, in the spirit of public service, I had agreed to donate 50% of the value of any time I spent on the project, on a pro bono (free) basis. While Fatheringham & Patterson could command over $120/hour for their time, my standard billing rate, starting out at that time, was $80/hour. That meant the district was getting my time for about $40/hour. It seemed like an obvious bargain for the county, by any standard.

Bargain or not, Kane County Commissioner Al Pompum pitched a fit. He didn’t want me to have anything to do with the district. Like me, Pompum was a “move-in,” but literally was a wolf in sheep’s clothing who had somehow managed to get elected as county commissioner, and then essentially became a one-man wrecking ball for the county.

I had locked horns with Commissioners Pompum, Don Lowe, and Garth Madsen when I first arrived in Kanab, over their termination of OraJean Hamblin, as the Kane County Travel and Tourism Director (which is another story that will have to wait for another day). More recently, I had locked horns even more seriously with the county over its campaign (ramrodded by Pompum and Lowe) to claim and essentially steal all unbranded cattle on Fifty-mile Mountain from Chet and Maggie Rawlins.

Pompum, who became the ring leader, was a California transplant, who along with everything else he purported to know, had a lot of ideas about how to change and improve Kane County (he and Kenneth McCoy had roughly equivalent personalities, temperaments and objectives, and would have made a pair to choose from). Pompum pretended to be a cowboy, and although he had originally “be-friended” Chet and Maggie Rawlins by giving them an outlaw horse that had dumped him off a cliff, breaking his neck (with friends like that, who needs enemies?), when they hadn’t been in a position to pay him anything for the horse, he set out to do everything possible to put them out of the cattle business.

Although Commissioner Pompum never forgot or forgave me for the pounding we gave the county in the OraJean Hamblin case, luckily, Commissioner Lowe didn’t get re-elected, and Commissioner Madsen didn’t take it quite as hard. So, once the Hamblin case was over, like newly elected commissioner, Henry Chamberlain, Commissioner Madsen became an ardent supporter of the water conservancy district. In fact, through his daughter(s)-in-law and granddaughters, Commissioner Madsen actually coordinated and provided some of the work force necessary for the labor-intensive task of putting together information packets that had to stuffed in envelopes and sent out to anyone who owned property in Kane County (some 10,000+ different parcels), in order to meet the legal requirements to establish the district.

Although drafting and review of the necessary documents was primarily Fatheringham & Patterson’s responsibility, we had to research every property owner in the entire county, take the paperwork Fatheringham & Patterson had drafted, make any necessary revisions, copy it, and put together and send out a packet of information, including a ballot, to vote for or against creation of the water conservancy district, by certified mail, return receipt requested, to each and every person who had any ownership interest of record in property in the entire county.

One of the things I had learned as the executive editor of the Utah Law Review is that hopefully you can pay enough attention to detail, but you can never pay too much attention to detail. In fact, I had adopted a little saying to that effect, and repeated it often to remind myself and my staff about just how exacting the practice of law can be: “hopefully we can pay enough attention to detail, but we can never pay too much,” I reminded them over and over again, as we sought to do things right.

Between my first year clerking for Armstrong & Spencer in Cedar City; the second year at O’Malley, Savanaugh, Quinn & Taylor, in Ithaca, New York; two summers at Clayton, Billings & Templeton, during law school; not to mention my law school experience, including my stint as executive editor of the Utah Law Review; I did feel like I had some pretty good foundational understanding about what it meant to try to “do things right.”

Despite having set up shop in a small, isolated, rural community like Kanab, Utah, I still wanted to try to practice law at the highest, most professional level possible, under the circumstances, and have our office be as professional, and always turn out the best, most professional legal work product possible.

And that is one of the reasons I recommended hiring Fatheringham & Patterson, and why I appreciated working with them — because they, too, seemed to have high standards of professionalism and work quality, and I had a great deal of respect and admiration for the way they practiced law. Plus, with a practice as isolated as mine was, it was always nice to have professional company, so to speak, and someone to talk to. In addition to having access to Terry Spencer and Chance Armstrong in our own firm, by working with the attorneys at Fatheringham & Patterson to create the water conservancy district, Orrin Patterson and Robert Fatheringham became some of my mentors and friends in the practice of law. With their able guidance and assistance we jumped through all the necessary hoops to get the water conservancy district off the ground in Kane County, and on solid footing.

And that is one of the reasons I recommended hiring Fatheringham & Patterson, and why I appreciated working with them — because they, too, seemed to have high standards of professionalism and work quality, and I had a great deal of respect and admiration for the way they practiced law. Plus, with a practice as isolated as mine was, it was always nice to have professional company, so to speak, and someone to talk to. In addition to having access to Terry Spencer and Chance Armstrong in our own firm, by working with the attorneys at Fatheringham & Patterson to create the water conservancy district, Orrin Patterson and Robert Fatheringham became some of my mentors and friends in the practice of law. With their able guidance and assistance we jumped through all the necessary hoops to get the water conservancy district off the ground in Kane County, and on solid footing.

(For more on this subject SEE Johnson Canyon Water Prophet).