As I was trying to get rolling making rain as a country lawyer, I met Chet and Maggie Rawlins the Spring of ‘92. They definitely weren’t golfers (See Lawyers are Supposed to be Golfers). I’d been out of law school almost a year. I had been practicing law in Kanab since the previous August, just after taking the bar exam, and had been admitted to the Utah bar in October.

As I was trying to get rolling making rain as a country lawyer, I met Chet and Maggie Rawlins the Spring of ‘92. They definitely weren’t golfers (See Lawyers are Supposed to be Golfers). I’d been out of law school almost a year. I had been practicing law in Kanab since the previous August, just after taking the bar exam, and had been admitted to the Utah bar in October.

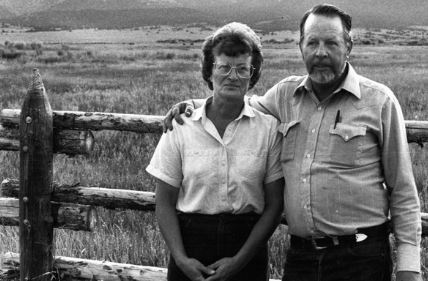

They had made an appointment to come see me about one of several legal problems they were experiencing at the time, that they wanted to discuss with an attorney. When they came in, I couldn’t quite tell how old Chet was, but I figured him to be about 65 (turns out it was more like 75). Maggie’s age was likewise something of a mystery, but she looked about 35. They were kind of a mis-matched pair, age-wise. Obviously, he could have been her father or even grandfather.

But based on their appearance, I was able to size them up pretty quick. I had grown up in a western agricultural family, around more than a few ranchers, cowboys, and horsemen. I knew what real ones were supposed to look like, and I could tell they were the real McCoy.

I could tell at a glance, from the look of his brown face, and tall, lanky body, with long bowed legs, and  weathered brown, big-knuckled hands, that Chet would be real, what true cowboys call “forked,” (which contrary to how it may sound, is one of the highest compliments that can be paid to a true horseback cowboy). He was slim and well-kept. He had on a big black hat; plain, pearl snap shirt with the top button buttoned; and a well worn leather belt with a plain, tarnished, looping, diamond-shaped copper buckle. No fancy, platter-sized silver trophy buckle. Instead of wranglers, he wore Levi’s, with a single cuff rolled at the bottom, over the top of high-heeled riding boots. Having been around a few real good, old-style, ranch cowboys in my life, I could see that Chet Rawlins wasn’t some fancy, schmancy rodeo cowboy wannabe. I could tell, just looking at him that he was made to sit a horse. Just sitting there, straight as an arrow, I could clearly envision him horseback, astride a worthy mount.

weathered brown, big-knuckled hands, that Chet would be real, what true cowboys call “forked,” (which contrary to how it may sound, is one of the highest compliments that can be paid to a true horseback cowboy). He was slim and well-kept. He had on a big black hat; plain, pearl snap shirt with the top button buttoned; and a well worn leather belt with a plain, tarnished, looping, diamond-shaped copper buckle. No fancy, platter-sized silver trophy buckle. Instead of wranglers, he wore Levi’s, with a single cuff rolled at the bottom, over the top of high-heeled riding boots. Having been around a few real good, old-style, ranch cowboys in my life, I could see that Chet Rawlins wasn’t some fancy, schmancy rodeo cowboy wannabe. I could tell, just looking at him that he was made to sit a horse. Just sitting there, straight as an arrow, I could clearly envision him horseback, astride a worthy mount.

Maggie cut a little different image. She was short and shapely. Slender waist circled by a buckstiched belt with her name stamped in back, and a good-sized silver buckle in front. She had on tight wrangler jeans over riding boots. Her face was soft and pretty, but her hands were hard and calloused. She was a looker; an attractive woman by any standard. She looked plenty forked too, although not quite as obviously so as Chet did (I guess maybe only more years and miles in the saddle can produce the more obvious look). Obviously a cowgirl, she was also the talker of the two.

Maggie cut a little different image. She was short and shapely. Slender waist circled by a buckstiched belt with her name stamped in back, and a good-sized silver buckle in front. She had on tight wrangler jeans over riding boots. Her face was soft and pretty, but her hands were hard and calloused. She was a looker; an attractive woman by any standard. She looked plenty forked too, although not quite as obviously so as Chet did (I guess maybe only more years and miles in the saddle can produce the more obvious look). Obviously a cowgirl, she was also the talker of the two.

I had actually expected to see more people like them around Kanab, but to my disappointment, in almost a year that I had been in practice, they were the first and most unequivocal real ranch cowboys that I had actually met so far.

After shaking hands all around and exchanging introductions and pleasantries, Maggie got right down to the matter at hand:

“D’you know Mel Harkiss?” she blurted.

“Yeah. . . yeah, I know Harkiss,” I responded.

Harkiss was something of a developer and promoter around town, with various projects in the works. Real estate-wise, Harkiss seemed to be one of the biggest movers and shakers in Kanab. He had three main projects that I was aware of. Ironically, he had been one of the major promoters and developers of the golf course in Kanab, and owned an undeveloped subdivision that surrounded it, which had been the center of a considerable amount of controversy in the community.

In addition, along with other partners, Harkiss had developed the Vermillion Ranchos Subdivision, a large, multi-phase housing development, across the creek, southwest of Kanab city proper, parts of which were tucked right up under the shadows of the redrock, vermillion cliffs that surrounded most of the town. For a variety of reasons, many of which seemed to point straight at Harkiss, the “Ranchos,” as the subdivision was most often referred to, had likewise become a veritable hotbed of controversy.

The controversies associated with the Ranchos, which seemed to cover just about everything about the subdivision, focused particularly on the roads, the quality of their construction, and the special improvement district that had been used to pay for them. Despite all the controversy, however, the Ranchos had been annexed into the city, and over time had actually grown to the point that its size and population almost seemed to dwarf the rest of the town. It had become almost like a separate residential community, with nothing but houses, roads and a church. When we first moved to Kanab, because of the controversies surrounding the subdivision, there was a real schism between people in the old part of town, and people who resided in the Ranchos subdivision. Most of the residents of the Ranchos were transplants, move-ins, or newcomers who had recently settled in Kanab, and had a little different mindset than the old-timers. Many of the newcomers who bought lots and built houses in the subdivision ended up being dissatisfied about a myriad of things, and wanted the city to do something about it. Most of the old-timers, who lived in the old part of town, were convinced that the subdivision was going to end up bleeding the city dry.

Harkiss had also developed Elk Creek Ranch, which had, at one time, been a pretty nice little working cattle ranch about 40 miles from Kanab, by chopping it up into 10 and 20 acre ranchettes, and maintaining kind of a dude ranch operation there. And, not surprisingly, it, too, had its own fair share of controversy.

“D’you do any legal work for Harkiss?” was Maggie’s next question.

“No. . . no, I’ve never represented him.”

When I first moved to Kanab, Harkiss’ public reputation was something I was both keenly aware of, and more than a little gun shy about. It seemed like almost everything he had touched or had anything to do with had become a big source of controversy.

After my arrival, Harkiss had tried to retain me a time or two, but as willing as I seemed to be to take on just about anything, I had seen enough of his tarnished reputation to conclude that in terms of local political correctness, it might be pure suicide to get too tangled up with Mel Harkiss. Controversy can be a great opportunity for lawyers — unless it backfires. So I always declined his overtures.

On that score, I had taken part of my cue from Saul Beaumont, another Kanab notable at the time, who was likewise a real estate investor and small-scale developer in his own right. “Tall Saul,” as he was known, was a mountain of a man, and unlike Harkiss, a real plain talker. With steel gray hair, he was getting on towards middle age, and looked like he probably had more than his fair share of miles. In addition to being real tall, he had broad shoulders, big hands and feet. He looked and talked like the kind of guy you’d hate to meet in a dark alley; the kind of guy that could probably take-on several normal men. But actually credibility and integrity were his highest objectives.

On that score, I had taken part of my cue from Saul Beaumont, another Kanab notable at the time, who was likewise a real estate investor and small-scale developer in his own right. “Tall Saul,” as he was known, was a mountain of a man, and unlike Harkiss, a real plain talker. With steel gray hair, he was getting on towards middle age, and looked like he probably had more than his fair share of miles. In addition to being real tall, he had broad shoulders, big hands and feet. He looked and talked like the kind of guy you’d hate to meet in a dark alley; the kind of guy that could probably take-on several normal men. But actually credibility and integrity were his highest objectives.

Saul had a real estate license, with an office at Century 21 Realty, right next door to mine, where, along with managing his own extensive real estate holdings, he pretty much just did his own thing. I had done a little legal work for Saul, and we had gotten to be pretty good friends.

One day I’d heard through the grapevine, but had a hard time believing, based on our previous discussions, that Tall Saul was making some kind of deal with Harkiss. So the next time I saw him, I hit him up about it. When I asked him, Saul looked at me real strange; burst out laughing, then roared: “I don’t care what happens . . . I don’t care if hell freezes completely over, but I will never, ever . . . mark my word on this . . . you can take it to the bank . . . I will never do business with Mel Harkiss!”

I guess that pretty much put that rumor to rest, and right or wrong, more or less summed up my own policy about getting tangled up with Harkiss.

I guess that pretty much put that rumor to rest, and right or wrong, more or less summed up my own policy about getting tangled up with Harkiss.

“What d’you think of Harkiss?” Maggie asked.

Now that was a harder question. I had consciously avoided any real personal or professional involvement with him, so I didn’t really have any personal basis on which to pass any sort of judgment.

“I guess I haven’t had enough to do with him to really be able to form much of an opinion,” I responded. “But I know what a lot of other people think, and it doesn’t seem to be very good.”

“Well, we’ve got a little problem with Harkiss that we kinda wanted to discuss with you, so we just wanted to know where you’re comin’ from,” Maggie said as she handed me a letter. “We got this letter from Richard Galliston, one of Harkiss’ attorneys from St. George, and we just wanted to talk to you, and see what you thought of it. . . . Can I kinda tell you what happened while you’re lookin’ at it?”

One thing I had learned early on in practice is that there are always at least two sides to every story, and sometimes more, depending on how many different parties are involved. Because Harkiss had had his high-powered St. George attorney write Rawlinses a letter, based on what I’d seen and heard so far, I suspected there would be a big difference in the respective stories in this case, so I nodded affirmatively.

That was my start with Chet and Maggie Rawlins — but it was just the start. I quickly came to learn that they were, at least temporarily, “legal lightning rods,” and because of their assortment of legal “challenges,” I had the opportunity to get to know them quite well over the course of the next few months — before Chet died — and I ended up going on to work with Maggie for years to come.