Lawyers who are highly productive financially are known as Rainmakers.

Lawyers who are highly productive financially are known as Rainmakers.

In the good ol’ days, a typical country lawyer might have just sat around his office reading the paper, taking a case or two here and there, whatever came along, without too much stress or unreasonably high financial expectations.

That’s the kind of life I thought I was setting myself up for, back in 1990, when I decided to settle in Kanab — a small town on the Utah/Arizona border — the diverse practice and relatively kicked-back lifestyle of a country lawyer, in a quiet, rural community.

But those aspirations ended up being relatively short-lived. Times have changed. In this day and age, regardless of how good an attorney may be (especially in a small town), his/her success as an attorney will be judged by the general public almost exclusively by all the obvious signs of financial success, based largely on all the outward manifestations — big houses, expensive cars, fancy clothes, and lots of toys.

In my opinion, that reality is magnified in Utah, where regardless of predominant Christian religious doctrine to the contrary, affluence and the desire for it, is one of the biggest driving forces behind the underlying culture. Under local circumstances, with rare exceptions, regardless of all the other pressures a young lawyer might feel, none of those pressures exceed the pressure to simply produce — financially — or make rain, as lawyers call it.

In my opinion, that reality is magnified in Utah, where regardless of predominant Christian religious doctrine to the contrary, affluence and the desire for it, is one of the biggest driving forces behind the underlying culture. Under local circumstances, with rare exceptions, regardless of all the other pressures a young lawyer might feel, none of those pressures exceed the pressure to simply produce — financially — or make rain, as lawyers call it.

In one of my earliest and most serious discussions with Terry Spencer, after we opened the Kanab branch office of Armstrong & Spencer, Attorneys at Law, he wanted to make sure I clearly understood what was expected. After discussing the status of the office, a couple of specific cases, and how things were going generally, Terry laid it out on the table:

“Mac, you’ll come to find that 90% of what we end up talking about is money.”

He really wasn’t telling me anything I didn’t already know. Between going to law school and having worked at three different law firms, including Armstrong & Spencer for over a year prior to law school, I had gotten to know enough lawyers that I had pretty much been able to figure out what makes them tick and what makes their world go round. But after climbing up on the soapbox, TS went on to preach a pretty good, unforgettable sermon:

“In a private law practice like ours, essentially everything has financial implications, and boils down to the issue of money. It’s a little different for us than it is for, say, a county attorney like Tim Stankey. . . . Our reputations as lawyers; our images in the community; how we perform; whether we win or lose; how many cases and what kinds of clients we have, all have financial implications. . . . You can be as idealistic or philosophical about it as you want. . . . Helping people, resolving problems, public service, yada, yada, yada . . . . But the bottom line is it all boils down to money. It’s the financial reality of life. Or the financial reality of the

good life, I suppose. . . . . Money is like the rain that makes the grass grow. . . . You’re a farm boy, so you should understand that. The more rain we get, the better the grass grows; everything is green, and the world is a great place to be. If there’s not enough rain, the grass stops growing. What grass there is wilts and turns brown. When there’s not enough to go around, everything starts to stress, and it’s a problem. . . . that’s the way it is around here too.”

I nodded to convey my understanding of what he was saying.

“As you know, we’ve had quite a few associates come and go over the years. They usually seem to have some challenges and struggles in the revenue department and pulling their own weight, financially. Sometimes it almost seems like we need to start a cloud seeding program for associates,” he said with a chuckle, “but we’ve known you for quite a while now; we’ve got a lot of confidence in you and your ability to get a good start and pull your own weight and then some. . . You’re young, smart, energetic, capable and willing to work hard, so just get out there and make rain while the sun shines!”

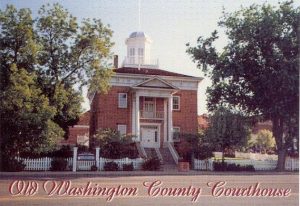

Despite already having a good, basic understanding of this reality, it still sounded like quite a charge. Kanab had a real checkered past with attorneys. Southern Utah legal communities can be interesting, and  sometimes a little hard to figure out. Unlike the explosive growth of the St. George and Washington County legal community, for instance, that had grown even faster than the population of the area itself (in the past 25 years, the legal community had grown from about 20 lawyers to close to 120), up to that point, Cedar City, on the other hand, had experienced a completely different scenario. Despite substantial growth in the Cedar City and the Iron County populations, the size of the corresponding legal community had remained relatively static (in about a 30 year period, there had always been about 20 lawyers in Iron County — not the same 20; some died, others retired, some became judges, some moved away, others moved in, but the relative size of the legal community itself had experienced little change).

sometimes a little hard to figure out. Unlike the explosive growth of the St. George and Washington County legal community, for instance, that had grown even faster than the population of the area itself (in the past 25 years, the legal community had grown from about 20 lawyers to close to 120), up to that point, Cedar City, on the other hand, had experienced a completely different scenario. Despite substantial growth in the Cedar City and the Iron County populations, the size of the corresponding legal community had remained relatively static (in about a 30 year period, there had always been about 20 lawyers in Iron County — not the same 20; some died, others retired, some became judges, some moved away, others moved in, but the relative size of the legal community itself had experienced little change).

Historically, Kane County’s legal community had been nothing short of volatile. In fact, there had been long periods of time when there hadn’t even been any attorneys in Kane County. If Kanab hadn’t been the county seat, like Fredonia, its twin-town across the border, in Arizona, Kanab may have never had an attorney. But even though Kanab is the Kane County seat, and has been since the inception of statehood, most attorneys who ever tried to make a go of it, practicing law in the small, isolated community on the skirts of the Arizona Strip, starved out and moved on.

For years, this forced anyone who needed legal services, including Kane County, Kanab City, and all the little towns around, to go elsewhere for legal counsel, thus explaining the long tenure of Darrel Snow, a sharp St. George attorney, as legal counsel for Kanab City, and Keith Pendleton and/or his partner, Stan Young, from Richfield, to fill in, off and on, for years, as county or district attorneys covering Kane County.

Things finally started to stabilize in the Kane County legal community when Paula Heaton Hamblin, a hometown girl made good and went to law school. She returned in about 1980. Despite stellar law school credentials that probably could have taken her just about anywhere, Paula Heaton was born and raised in Kanab, the daughter of hearty pioneer stock, and when she came home, she got married, and settled down for good. For the better part of a decade, Paula was the Kane County legal community. After several terms as Kane County Attorney, however, she was appointed Kane County Justice Court Judge, leaving yet another void in the county attorney’s office, which maverick attorney Tim Stankey seemed ready, willing and anxious to fill.

As a heavy drinker, smoker and unconventional non-conformist in a predominantly Mormon community, focusing primarily on criminal defense work, Stankey was almost the exact opposite of Paula Hamblin, and had been a black sheep attorney in St. George for a number of years. Apparently, by the time Judge Hamblin took the local bench, Stankey was ready to essentially seek exile, as the Kane County Attorney. So for several years, Stankey was the only actively practicing attorney in Kanab, and, as the community had grown, from all appearances, he had his hands full.

By the time I was halfway through law school, sizing up Kanab’s prospective professional opportunities, although Darrel Snow was still the city attorney, besides Judge Paula Hamblin, who wasn’t really practicing, there were actually two practicing attorneys in Kane County: Tim Stankey and Marsha Alexander.

By the time I was halfway through law school, sizing up Kanab’s prospective professional opportunities, although Darrel Snow was still the city attorney, besides Judge Paula Hamblin, who wasn’t really practicing, there were actually two practicing attorneys in Kane County: Tim Stankey and Marsha Alexander.

Marsha was another black sheep in the very small flock of black sheep that made up the Kane County legal community. She was one of the plural, polygamous wives of Joseph Alexander, and lived with the Alexander Clan in Big Water. Unlike the fundamentalists who continued to practice so-called “Mormon-style” polygamy according to the dictates of their own church in Colorado City, Arizona and Hildale, Utah (twin communities located on the Utah/Arizona Border, which were jointly referred to, locally, as “Short Creek” or “The Creek”), Alexanders practiced a completely different brand of plural marriage. Theirs’ seemed to be a more new-age, free and open style of polygamy, than the Short Creek variety. It didn’t seem to have anything to do with fundamental Mormonism, and they certainly didn’t look and act like the Short Creek polygamists.

I don’t know how many wives Joe Alexander had over time, and/or how he pulled it off, and I never did completely grasp his apparent appeal to the female gender, but as a general rule, in contrast to most Short Creek wives, Joe’s wives were typically a lot more assertive, well-educated, seemingly capable, and self-expressed (not to mention attractive) women. One was a real estate agent. Another was an accountant. One was the town clerk. And Marsha, or “Shay” as she had come to like to be called, was an attorney. Shay Alexander was the Big Water Town Attorney, had been the Kane County Public Defender when she wasn’t feuding with Tim Stankey, and was currently serving as the Kanab City Public Defender.

The current status of the Kane County legal community was probably one of the primary reasons for my decision to give Kanab a try, not to mention being able to talk Terry Spencer and Chance Armstrong into backing me.

I was looking for a good professional opportunity in a small rural community. The way I had it figured (and I couldn’t detect any divine response to the contrary), Kanab had already experienced quite a bit of growth and was bound to grow some more. There had to be a significant, unmet demand for private legal services in Kane County, and very little competition for the available work. Tim Stankey and Shay Alexander obviously weren’t handling it all. The entire county was growing, and obviously, Kanab City, Kane County and their residents had a number of legal needs that weren’t being met by resident attorneys. Although many of the locals continued to maintain that any attorney who attempted to rely solely on a private practice to survive in Kane County would end up starving out just like all the predecessors; we all (Chance Armstrong, Terry Spencer, and myself) viewed it to be a great business/professional opportunity, ripe for the picking by the right person, and we simply hoped that person would be me.

Watch for more in the Range Wars & Legal Tales series — by Mancos MacLeod

Lawyers are Supposed to be Golfers

Water Lawyer: Whiskey’s for Drinking; Water’s for Fighting

Welcome to the Neighborhood of Sharp Knives and Rogue Stallions

You may also like

-

Between Fences and Firearms, Part 2 — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Between Fences and Firearms — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Kangaroo Court — Range Wars and Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Cow Lawyer — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Real People for Clients — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod