The past few years have been very eventful on the Western “public lands” front. I put quotation marks around the term/phrase “Public Lands” because according to my evolving understanding, the true and correct definition of “public lands” are lands open to entry and settlement (i.e., there has been no prior entry or settlement), and upon which there are no prior rights or claims. In a nutshell, what this means is that public lands are those lands and resources upon which no one has made any kind of claim. But regardless of the proper terminology and reference regarding these lands, there is no question about the term “Debate.” A very lively debate, akin to the original Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate, is now raging in the West over jurisdiction, control and management of the so-called “public lands,” claimed by the Federal Government..

The past few years have been very eventful on the Western “public lands” front. I put quotation marks around the term/phrase “Public Lands” because according to my evolving understanding, the true and correct definition of “public lands” are lands open to entry and settlement (i.e., there has been no prior entry or settlement), and upon which there are no prior rights or claims. In a nutshell, what this means is that public lands are those lands and resources upon which no one has made any kind of claim. But regardless of the proper terminology and reference regarding these lands, there is no question about the term “Debate.” A very lively debate, akin to the original Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate, is now raging in the West over jurisdiction, control and management of the so-called “public lands,” claimed by the Federal Government..

Not even counting Bunkerville and the whole Bundy situation, over the course of the last 2-3 years, and especially the past year, this debate has been ratcheted up several notches, with major MSM and social media debate, and ongoing live protests, including sustained protests about treatment of Dwight and Steven Hammond, the resulting Oregon Stand-off, including the Malheur Occupation and associated trial(s), the prosecution and trial of San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman, ongoing protests about the Bears Ears and Gold Butte National Monument designations, and continuing concerns about the possibility of an Owhyee Canyonlands National Monument as well.

In at least one prior piece in our Realities that Nobody Wants to Talk About series, we touched on some of this. In this piece we are going to take a realistic look at Utah’s role in the whole discussion and debate. We’re also going to talk about one element or component of the discussion that seems to be a major sticking point.

But before addressing that sticking point, let’s look at Utah’s ongoing role in the discussion.

Although the federal lands transfer proposal is just one aspect of the overall public lands discussion/debate (which is clearly a somewhat complex equation, with many moving parts), it is well-known that Utah has taken the lead regarding the federal land transfer movement, passing state legislation in support of that proposal back in 2012, followed by additional legislation in 2016 outlining how it would manage federal lands if/when they are transferred. Utah also created what it calls the “Public Lands Policy Coordinating Office” (PLPCO), and the so-called “Constitutional Defense Council” (CDC), and hired former national BLM director, Kathleen Clarke to run with these efforts. All this was viewed to be a very bold move in assuming some sort of mantle of leadership in this movement.

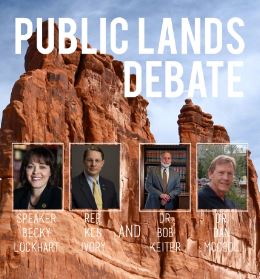

From 2012 to 2016, with Utah State Legislator Ken Ivory and the Utah-based American Lands Council leading the charge, the federal land transfer movement seemed to be gaining steady traction and momentum. Many rural counties were completely on board, and moving strongly in that direction, with other Western states getting on board or showing significant interest. During that time period Ken Ivory, and then Utah House Speaker Becky Lockhart participated in a series of well-publicized public debates through-out the state of Utah advocating the land transfer proposal. Even the Bundy Standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada in 2014 seemed to add substance to the movement by providing yet another clear example of federal overreach and heavy-handedness. Despite Cliven Bundy’s oft-perceived indiscretions with respect to refusal to pay federal “grazing fees,” many Utah elected officials and political leaders joined the chorus condemning the Federal Government’s heavy-handed approach in Bunkerville. And between 2014 and 2016, Utah legislator (and retired BLM employee) Mike Noel led the charge on drafting and sponsoring the Utah Public Lands Management Act, which enjoyed broad legislative support in 2016, and passed with flying colors. And the Utah State legislature also approved allocation of substantial sums of money ($4.5MM initially, and ultimately up to $14MM) to litigate the federal transfer issue. There is no question, no other Western state has been as active or played as big a leadership role in the whole discussion.

From 2012 to 2016, with Utah State Legislator Ken Ivory and the Utah-based American Lands Council leading the charge, the federal land transfer movement seemed to be gaining steady traction and momentum. Many rural counties were completely on board, and moving strongly in that direction, with other Western states getting on board or showing significant interest. During that time period Ken Ivory, and then Utah House Speaker Becky Lockhart participated in a series of well-publicized public debates through-out the state of Utah advocating the land transfer proposal. Even the Bundy Standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada in 2014 seemed to add substance to the movement by providing yet another clear example of federal overreach and heavy-handedness. Despite Cliven Bundy’s oft-perceived indiscretions with respect to refusal to pay federal “grazing fees,” many Utah elected officials and political leaders joined the chorus condemning the Federal Government’s heavy-handed approach in Bunkerville. And between 2014 and 2016, Utah legislator (and retired BLM employee) Mike Noel led the charge on drafting and sponsoring the Utah Public Lands Management Act, which enjoyed broad legislative support in 2016, and passed with flying colors. And the Utah State legislature also approved allocation of substantial sums of money ($4.5MM initially, and ultimately up to $14MM) to litigate the federal transfer issue. There is no question, no other Western state has been as active or played as big a leadership role in the whole discussion.

But unfortunately, just as the whole discussion and debate were reaching fever pitch with the Oregon Standoff, and prolonged protests regarding proposed National Monument designations, in 2016 momentum for the movement started meeting serious resistance, and it started losing traction. While it was well known that it would have been a virtual impossibility under a Hillary Clinton Administration, when Donald Trump was surprisingly/miraculously elected, there had been genuine hope that he might get on board to make it happen. Amazingly, in ongoing roller-coaster-like developments, Trump’s appointment of Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke as Secretary of the Interior has pretty much dashed that hope. But that’s certainly not the only issue that needs serious attention, including that sticking point that we’re going to be talking about

The first major set-back in the land transfer effort, however, resulted from the media firestorm surrounding the Malheur Occupation and Oregon Stand-off in early 2016. Other than a general feeling of dissatisfaction with federal land and resource management, there was really no actual, direct connection between the so-called “Oregon Standoff,” and the federal land transfer movement. But despite the lack of any actual connection between the two, in the Mainstream Media narrative and rhetoric that ensued, fueled by an opportunistic environmental agenda, the Malheur Occupation and the federal lands transfer movement became connected in many peoples’ minds. In the distorted, label-rich media feeding frenzy, they were both characterized as “land grabs.” And in the process the transfer movement was dealt a significant blow that it has been attempting to recover from ever since.

The first major set-back in the land transfer effort, however, resulted from the media firestorm surrounding the Malheur Occupation and Oregon Stand-off in early 2016. Other than a general feeling of dissatisfaction with federal land and resource management, there was really no actual, direct connection between the so-called “Oregon Standoff,” and the federal land transfer movement. But despite the lack of any actual connection between the two, in the Mainstream Media narrative and rhetoric that ensued, fueled by an opportunistic environmental agenda, the Malheur Occupation and the federal lands transfer movement became connected in many peoples’ minds. In the distorted, label-rich media feeding frenzy, they were both characterized as “land grabs.” And in the process the transfer movement was dealt a significant blow that it has been attempting to recover from ever since.

One of the main reasons that happened is because neither Ammon Bundy on one side of the equation, nor the American Lands Council and others leading the land transfer movement, on the other side of the equation, appeared to be very well-prepared to control the media narrative coming out of the Malheur Occupation, which became very negative right from the get-go.

With the help of a more than willing Mainstream Media, Environmentalists seized the opportunity to run wild with the narrative to advance their agenda. According to Dave Skinner in a special report in Range magazine, “Simply put, the refuge occupiers didn’t have a clue how to fight a war of words on America’s media battlefield.” According to Skinner, “Prior to the standoff, Environmentalism Inc and other defenders of bad federal-lands policy were on the political defensive. But within hours of the Bundy Refuge takeover, professional Greens went on full-bore offense. Green cash and people poured into Harney County while home-office staff lit up the wires to news outlets nationwide.”

Obviously, neither the refuge occupiers, nor the completely separate players behind the land transfer movement were prepared to deal with the ensuing media firestorm. Fueled by a combination of their normal liberal agenda and biases, coupled with a narrative provided by environmental organizations like the Center for Biological Diversity, the Center for Western Priorities, and Western Watersheds, the mainstream media ran wild with the environmentalists’ narrative. A common theme advanced by all those groups was that the Koch Brothers were funding all of it – that the Koch Brothers were funding ALC, and that they had funded and staged the Malheur Occupation — every part and parcel of it was dictated by the Koch Brothers’ agenda. According to that narrative, the Koch Brothers were calling all the shots and funding everything, and everyone from Cliven Bundy to Ken Ivory to LaVoy Finicum were nothing more than hapless Koch Brothers pawns.

Obviously, neither the refuge occupiers, nor the completely separate players behind the land transfer movement were prepared to deal with the ensuing media firestorm. Fueled by a combination of their normal liberal agenda and biases, coupled with a narrative provided by environmental organizations like the Center for Biological Diversity, the Center for Western Priorities, and Western Watersheds, the mainstream media ran wild with the environmentalists’ narrative. A common theme advanced by all those groups was that the Koch Brothers were funding all of it – that the Koch Brothers were funding ALC, and that they had funded and staged the Malheur Occupation — every part and parcel of it was dictated by the Koch Brothers’ agenda. According to that narrative, the Koch Brothers were calling all the shots and funding everything, and everyone from Cliven Bundy to Ken Ivory to LaVoy Finicum were nothing more than hapless Koch Brothers pawns.

Fortuntately, despite all the distorted media spin, Ammon Bundy got his day in court and received vindication when he was fully acquitted by a federal jury in Portland. But it is unlikely that the federal land transfer movement will have any meaningful opportunity for such vindication.

A big part of the predatory media feeding frenzy that ensued and still continues is widespread use of a whole host of inflammatory labels (like “extremists,” “militants,” “domestic terrorists,” etc.), coupled with asserted guilt by association. One of the most telling and damaging examples of this was Oregon Senator Ron Wyden’s widely-reported statement that the Standoff was “a situation where the ‘virus’ was spreading,” and strong action needed to be taken.

A big part of the predatory media feeding frenzy that ensued and still continues is widespread use of a whole host of inflammatory labels (like “extremists,” “militants,” “domestic terrorists,” etc.), coupled with asserted guilt by association. One of the most telling and damaging examples of this was Oregon Senator Ron Wyden’s widely-reported statement that the Standoff was “a situation where the ‘virus’ was spreading,” and strong action needed to be taken.

Exactly, what the so-called “virus” was is debatable. Some say it was “extremism”. Others say it was “the truth.” Yet others say it was the so-called “militia.” But from my perspective, the real thing that was spreading that the likes of Senator Wyden were most concerned about is the principle underlying the major sticking point that we’re going to talk about. It is what I have come to refer to as a “Gospel.” What does “gospel” mean? According to the Greek translation, it means “Good News,” or “Good Message.” It’s what I call the Gospel — the Good News — of Property Rights.

“The proper function of government is not to grant rights, but to protect the unalienable, God-given rights of life, liberty, property, and pursuit of happiness.”

One thing is for sure, the entire situation, evolutions and atmosphere coming out of the Malheur Occupation caused a whole lot of new information to come out of the woodwork, and provided opportunities to find out where a whole bunch of people really stand on a variety of basic principles, including the sticking point we keep referring to — the concept of fundamental property rights. Although Senator Wyden is a liberal democrat from one of the most liberal states in the West, unfortunately, even so-called “conservative” politicians and policymakers in an ultra-conservative state the likes of Utah seem to drink the same Kool-aid when it comes to the issue of fundamental property rights. Although the Utah State Republican Platform expressly states: “The [proper] function of government is not to grant rights, but to protect the unalienable, God-given rights of life, liberty, property, and pursuit of happiness,” when it comes to actions speaking louder than words, it has become quite clear that very few Utah political leaders really mean what they say.

One thing is for sure, the entire situation, evolutions and atmosphere coming out of the Malheur Occupation caused a whole lot of new information to come out of the woodwork, and provided opportunities to find out where a whole bunch of people really stand on a variety of basic principles, including the sticking point we keep referring to — the concept of fundamental property rights. Although Senator Wyden is a liberal democrat from one of the most liberal states in the West, unfortunately, even so-called “conservative” politicians and policymakers in an ultra-conservative state the likes of Utah seem to drink the same Kool-aid when it comes to the issue of fundamental property rights. Although the Utah State Republican Platform expressly states: “The [proper] function of government is not to grant rights, but to protect the unalienable, God-given rights of life, liberty, property, and pursuit of happiness,” when it comes to actions speaking louder than words, it has become quite clear that very few Utah political leaders really mean what they say.

Unfortunately, some of the most telling information that has come out of the events of the past several years is that — in terms of actions speaking louder than words — most Utah political leaders do not believe in the concept of fundamental property rights — including private property interests in the split estates of the federal domain. This reality became crystal clear when the Utah State Legislature passed the Utah Public Lands Management Act which included no reference to “valid, prior  existing rights.” Despite the fact that the applicable ederal statutory clause is often completely ignored, even FLPMA — the Federal Lands Policy Management Act — expressly states that the Act itself is subject to all valid, prior-existing rights, which includes RS-2477 access rights, water rights, and grazing rights, all established by the same fundamental, guiding principles — prior appropriation and beneficial use. But unfortunately, instead of recognizing and embracing these fundamental principles, Tony Rampton, Utah’s Assistant Attorney General assigned to help champion these issues, acting under the direction of Kathleen Clarke, PLPCO and the CDC, acting in concert with the Utah Farm Bureau and other entities, have gone to great lengths to pour cold water on the whole concept of fundamental property rights espoused by the likes of Dr. Angus McIntosh and Dr. Michael Coffman. While on one hand Utah’s political leaders have shown a strong united front in support of a federal land transfer, and have made a strong show of united opposition to the Bears Ears National Monument, on the other hand they have shown an equal lack of support for the concept of fundamental property rights, including “grazing rights” on federal grazing allotments, and whether such rights would have any more recognition or respect under state management if federal lands were transferred to the states. In terms of basic, fundamental principles, this reality is a serious wake-up call.

existing rights.” Despite the fact that the applicable ederal statutory clause is often completely ignored, even FLPMA — the Federal Lands Policy Management Act — expressly states that the Act itself is subject to all valid, prior-existing rights, which includes RS-2477 access rights, water rights, and grazing rights, all established by the same fundamental, guiding principles — prior appropriation and beneficial use. But unfortunately, instead of recognizing and embracing these fundamental principles, Tony Rampton, Utah’s Assistant Attorney General assigned to help champion these issues, acting under the direction of Kathleen Clarke, PLPCO and the CDC, acting in concert with the Utah Farm Bureau and other entities, have gone to great lengths to pour cold water on the whole concept of fundamental property rights espoused by the likes of Dr. Angus McIntosh and Dr. Michael Coffman. While on one hand Utah’s political leaders have shown a strong united front in support of a federal land transfer, and have made a strong show of united opposition to the Bears Ears National Monument, on the other hand they have shown an equal lack of support for the concept of fundamental property rights, including “grazing rights” on federal grazing allotments, and whether such rights would have any more recognition or respect under state management if federal lands were transferred to the states. In terms of basic, fundamental principles, this reality is a serious wake-up call.

A year or so after these issues first started colliding in full force, I recently had a chance to spend a signficant amount of time with Piute County, Utah rancher, Stanton Gleave, discussing all of this with him, in preparation for a big feature story about the Gleave family which will be coming out in the Summer 2017 issue of Range magazine.

I’ve written about some of this before, but if you’re not familiar with the name Stanton Gleave, it’s a name you’ll want to remember and pay attention to. Gleave is a Utah rancher, who has been near the epicenter of all these issues – and especially the property rights issue – for years. He is one of few people, including ranchers, who really “gets” the concept of private property rights and how they apply in the so-called public lands debate.

I’ve written about some of this before, but if you’re not familiar with the name Stanton Gleave, it’s a name you’ll want to remember and pay attention to. Gleave is a Utah rancher, who has been near the epicenter of all these issues – and especially the property rights issue – for years. He is one of few people, including ranchers, who really “gets” the concept of private property rights and how they apply in the so-called public lands debate.

Gleave presides over a sprawling family cattle and sheep ranching operation headquartered in rural Piute County, Utah – which some have suggested (and perhaps even hoped) might become the location of the next stand-off between ranchers in the West and the Federal Government. Not that Stanton Gleave is courting a confrontation or standoff with the federal government or anyone else, but few people probably understand as well as he does just how close that came to happening.

But one difference between Stanton Gleave and counterparts like the Bundys and LaVoy Finicum, is that Gleave doesn’t have a Facebook page. He wasn’t calling anyone to arms. He hasn’t been evangelizing any personal message. He doesn’t text or Twitter. He doesn’t even have a smart phone. And he didn’t go anywhere near Harney County, Oregon. But as conflict between the federal government and Western ranchers heated up in 2016, a lot of people, from politicians and so-called “patriots” to the media, started paying close attention to Stanton Gleave, beating a path to his door, and and watching closely to see what he might do. And for good reason, because a fuse was awfully close to being lit.

Consequently, politicians and policymakers were actively seeking him out, to hear his views, and to try to curry his favor and support, and he was summoned to testify before a state legislative committee. Although Gleave has also given many interviews over the course of the past year to everyone from NPR, SL Trib, The Guardian, Vice, etc., in virtually every case, they put their own spin on what he says and seek to distort his views to fit their own agendas.

Consequently, politicians and policymakers were actively seeking him out, to hear his views, and to try to curry his favor and support, and he was summoned to testify before a state legislative committee. Although Gleave has also given many interviews over the course of the past year to everyone from NPR, SL Trib, The Guardian, Vice, etc., in virtually every case, they put their own spin on what he says and seek to distort his views to fit their own agendas.

The thing is, Stanton has been around the block enough to know that state management of public lands, alone, is no silver bullet solution. In our upcoming Range magazine story, we will discuss the Gleave family’s own experiences with hard-core government overreach, harassment, and heavy-handed tactics by state government too. But for now let it suffice to say that Stanton Gleave has a very broad and experienced perspective. Consequently, he’s not always sure which is worse, “one tyrant 2000 miles away, or 100 tryants 200 miles away” — especially if neither one of them have any respect for property rights. Although Gleave acknowledges that there have been vast improvements in the state’s approach over the course of the past 10 years or so, he was sorely disappointed with some aspects of the recently enacted Utah Public Lands Management Act, including its lack of recognition of valid, prior existing rights.

Just to remove all possible doubt about his position, Stanton Gleave completely and wholeheartedly subscribes to the theory that Western ranchers own “grazing rights” in federal grazing allotments. He completely and wholeheartedly believes that in exactly the same way Western ranchers acquired ownership of homesteads, and water rights, under federal statutes based on widely recognized natural law principles of prior appropriation and beneficial use, Western ranchers also acquire a private property interest in the split water and forage “estates” of federal grazing allotments.

Just to remove all possible doubt about his position, Stanton Gleave completely and wholeheartedly subscribes to the theory that Western ranchers own “grazing rights” in federal grazing allotments. He completely and wholeheartedly believes that in exactly the same way Western ranchers acquired ownership of homesteads, and water rights, under federal statutes based on widely recognized natural law principles of prior appropriation and beneficial use, Western ranchers also acquire a private property interest in the split water and forage “estates” of federal grazing allotments.

According to Gleave, “The state doesn’t seem to get it either. Among other things, they don’t understand that there’s not really all that much left to transfer. If they understood the property rights concept, they would understand that most of the split estate resources on federal land have already been long-since disposed of under previous Congressional Acts, and federal actions.”

Although Stanton Gleave has broad natural resource experience, including years working for Kaibab Forest Industries in Southern Utah, given his livestock ranching roots and occupation, he is referring first and foremost to livestock ranching. Based on his upbringing, and study of the subject over the years, Gleave firmly believes that ranchers have “rights” – private property interests in the forage and water rights on federal grazing allotments. Those rights are and were acquired the same way as water rights throughout the West, and based on exactly the same principles — prior appropriation and beneficial use.

Although Stanton Gleave has broad natural resource experience, including years working for Kaibab Forest Industries in Southern Utah, given his livestock ranching roots and occupation, he is referring first and foremost to livestock ranching. Based on his upbringing, and study of the subject over the years, Gleave firmly believes that ranchers have “rights” – private property interests in the forage and water rights on federal grazing allotments. Those rights are and were acquired the same way as water rights throughout the West, and based on exactly the same principles — prior appropriation and beneficial use.

As Stanton and I were visiting and driving around Gleaves’ Piute County ranching operation headquartered in Kingston, he said, “Here’s a good example of what I’m talking about. . . . You know, Piute and Otter Creek Reservoirs raise some great fish.” Holding out his hands to demonstrate, he said “These reservoirs will raise 25-36” fish. They raise some really nice fish. . . . So now we’ve got all these fishermen and recreationists who think we ought to leave all the water in the reservoirs for raising fish and water-skiing. . . . But who do you think built those storage reservoirs decades ago? It was farmers and irrigation companies and water conservancy districts, that built the reservoirs to store water in the winter to irrigate with in the summer. . . .  Now, based on all the pressure from the sportsmen and recreationists, what do you think would happen if we went out and dammed-up the Sevier River and started trying to use all that water just for raising fish and water skiing? Or, what do you think would happen if I tried to keep and use all that water here in Piute County? . . . I mean, this is where it comes from. It’s ‘our’ water, right? . . . . Well, let me tell you, if I did that, I’d be in big trouble, because people downstream on the Sevier River have a superior right to that water. They have a superior right that was acquired by prior appropriation and beneficial use. They are the ones who built these storage reservoirs. If I tried to dam-up the river and steal their water, people downstream on the river, from Sevier County to Delta would be here with picks, shovels, pitchforks, guns and lawyers, to protect and take back their water rights, because they are treated as Rights. . . . And exactly the same principles apply to the forage and water on federal grazing allotments. Ranchers have acquired a private property interest and a right to use that forage and water by prior appropriation and beneficial use. . . And those rights need to be recognized and respected.

Now, based on all the pressure from the sportsmen and recreationists, what do you think would happen if we went out and dammed-up the Sevier River and started trying to use all that water just for raising fish and water skiing? Or, what do you think would happen if I tried to keep and use all that water here in Piute County? . . . I mean, this is where it comes from. It’s ‘our’ water, right? . . . . Well, let me tell you, if I did that, I’d be in big trouble, because people downstream on the Sevier River have a superior right to that water. They have a superior right that was acquired by prior appropriation and beneficial use. They are the ones who built these storage reservoirs. If I tried to dam-up the river and steal their water, people downstream on the river, from Sevier County to Delta would be here with picks, shovels, pitchforks, guns and lawyers, to protect and take back their water rights, because they are treated as Rights. . . . And exactly the same principles apply to the forage and water on federal grazing allotments. Ranchers have acquired a private property interest and a right to use that forage and water by prior appropriation and beneficial use. . . And those rights need to be recognized and respected.

So Stanton Gleave has summed it up in a nutshell. The concept of rights seems to be a sticking point. Rights have always been a sticking point. Among other things, the original Federalist/Anti-federalist debate was about protection of fundamental rights. Although that debate has never really ended, it did not even subside until the Constitution was amended to include the “Bill of Rights.” And it is unlikely that this debate is going to subside until these rights are fully recognized either.

All the same principles apply to water, forage and grazing rights. Until there is a recognition that they are indeed rights, there is going to continue to be a conflict – whether it’s with the federal government, the state, or environmental groups. According to Stanton Gleave, these are rights that must be recognized and protected. They are the rights that six generations of Gleaves have built a livelihood around, and according to Stanton, “The only way I’ve gotten where I am is by being stubborn and bull-headed, and if there is one thing I’m going to be stubborn and bull-headed about it is grazing rights. If the state of Utah isn’t willing to recognize those rights, I have no more use for what they’re trying to do than I do the federal government’s failure to respect these rights. At least FLPMA gives superficial lip service to these rights by making the Act ‘subject to all valid, prior-existing rights.’ But I can tell you this, ‘they are rights that my family and I will continue to stand-up and fight for’.”

All the same principles apply to water, forage and grazing rights. Until there is a recognition that they are indeed rights, there is going to continue to be a conflict – whether it’s with the federal government, the state, or environmental groups. According to Stanton Gleave, these are rights that must be recognized and protected. They are the rights that six generations of Gleaves have built a livelihood around, and according to Stanton, “The only way I’ve gotten where I am is by being stubborn and bull-headed, and if there is one thing I’m going to be stubborn and bull-headed about it is grazing rights. If the state of Utah isn’t willing to recognize those rights, I have no more use for what they’re trying to do than I do the federal government’s failure to respect these rights. At least FLPMA gives superficial lip service to these rights by making the Act ‘subject to all valid, prior-existing rights.’ But I can tell you this, ‘they are rights that my family and I will continue to stand-up and fight for’.”

What else is there to say? We just need first 10, then 100, and then 1000 more Stanton Gleaves. At that point fundamental property rights is a concept that’s going to be pretty tough to continue to ignore.

Ken Ivory, such massive holdings violate the “Equal Footing Doctrine.” The late Elko County Nevada Commissioner, Grant Gerber, rode his horse all the way from the Pacific Ocean to Washington, D.C. to protest overreaching federal management, and died on the return trip as a result of injuries incurred en route. Current Elko, County Commissioner Demar Dahl and Utah State Legislator Mike Noel both argue the states could do a much better job managing the land and resources themselves. According to Attorney Fred Kelly Grant, insistence on coordination with state and local government would make a big difference.

Ken Ivory, such massive holdings violate the “Equal Footing Doctrine.” The late Elko County Nevada Commissioner, Grant Gerber, rode his horse all the way from the Pacific Ocean to Washington, D.C. to protest overreaching federal management, and died on the return trip as a result of injuries incurred en route. Current Elko, County Commissioner Demar Dahl and Utah State Legislator Mike Noel both argue the states could do a much better job managing the land and resources themselves. According to Attorney Fred Kelly Grant, insistence on coordination with state and local government would make a big difference.