Recent discussions and accusations about people labelled as “Constitutionalists” and “Radical Constitutionalists” have raised questions about just how much any of us really know about the U.S. Constitution, how we got it, and what it really means — especially at this point. This piece is the first in a series that will attempt to address some of those questions, and to discuss how constitutional principles apply to everyday life. We’re going to try to keep each installment short and simple.

Recent discussions and accusations about people labelled as “Constitutionalists” and “Radical Constitutionalists” have raised questions about just how much any of us really know about the U.S. Constitution, how we got it, and what it really means — especially at this point. This piece is the first in a series that will attempt to address some of those questions, and to discuss how constitutional principles apply to everyday life. We’re going to try to keep each installment short and simple.

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philidelphia from May to September of 1787. After four long months of sweltering heat and humidity—and even more heated debate and deliberation—the delegates at last approved a final draft of the new Constitution on September 17, 1787. It had not been an easy task. Diverse agendas, personality conflicts, and regional differences all played a part. But in the end, compromises were reached, scores were settled, and the ultimate debate boiled down to the fundamental differences between two political camps: the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists.

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philidelphia from May to September of 1787. After four long months of sweltering heat and humidity—and even more heated debate and deliberation—the delegates at last approved a final draft of the new Constitution on September 17, 1787. It had not been an easy task. Diverse agendas, personality conflicts, and regional differences all played a part. But in the end, compromises were reached, scores were settled, and the ultimate debate boiled down to the fundamental differences between two political camps: the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists.

Adoption of the draft constitution by the Philadelphia Convention was just the beginning, however. Before the new Constitution could take effect and become law, it had to be ratified by at least nine of the thirteen states. If it was not ratified by at least 9 of the states, it would have simply gone away and would not have taken effect. Any state that voted not to ratify the Constitution would not be part of the new union and would remain an independent sovereign nation. After the draft constitution was adopted by those at the constitutional convention, the Federalist versus Anti-Federalist debate intensified, and the real debate began among the people.

The Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate

The formal debate between these competing factions occurred largely in writing, through what have become referred to as the Federalist Papers, which were written anonymously by a number of the founding fathers under a variety of pen names, and published in the major papers in the colonies at the time.

The formal debate between these competing factions occurred largely in writing, through what have become referred to as the Federalist Papers, which were written anonymously by a number of the founding fathers under a variety of pen names, and published in the major papers in the colonies at the time.

At the time, ratification of the Constitution by the states was by no means certain. Indeed, many people at that time opposed the creation of a federal, or national, government that would have power over the states. These people were called Anti-Federalists. They included, primarily, members of the middle class who were less likely to be a part of the wealthy, aristocratic elite than were members of their opposition, who called themselves Federalists. Anti-Federalist leaders included some of our most revered Founding Fathers, including leading national figures during the Revolutionary War period. Other Anti-Federalists were local politicians who feared losing power should the Constitution be ratified.

Federalists, on the other hand, came primarily from the wealthy, aristocratic class of merchants and plantation owners. They favored a centralized federal government that would govern the states as one large, continental nation. They supported government intervention in economic affairs and the creation of a national banking system.

The Bill of Rights

Although the Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate addressed many issues, eventually it came to focus almost entirely on the concept of a Bill of Rights. The Federalists opposed a Bill of Rights, and the Anti-Federalists were strong proponents of the need for a Bill of Rights.

Although the Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate addressed many issues, eventually it came to focus almost entirely on the concept of a Bill of Rights. The Federalists opposed a Bill of Rights, and the Anti-Federalists were strong proponents of the need for a Bill of Rights.

The addition of a bill of rights to the Constitution was originally controversial because the Constitution, as written, did not specifically enumerate or protect the rights of the people. Rather, it listed the limited powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Some prominent Federalists argued that any such enumeration, once written down explicitly, could later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had. In response to this assertion, in so-called Anti-Federalist No. 84, “Brutus” argued that government unrestrained by such a bill could easily devolve into tyranny. Other supporters of the bill argued that a list of rights would not and should not be interpreted as exhaustive; that these rights were merely examples of important rights that people had, but that people had other rights as well. People in this school of thought were confident that the judiciary would interpret these rights in an expansive fashion.

The lack of a bill of rights proved to be a very thorny issue, and several states simply refused to ratify the new Constitution without it, which was on track to prevent ratification of the constitution by a sufficient number of states for it take effect and create the intended union. Consequently, before the ratification process was complete, the first Ten Amendments were added to the Constitution, and it is these amendments that have become known as the “Bill of Rights,” to specifically address and protect certain inalienable rights bestowed by the irrefutable laws of nature, and those rights have become an important part of the United States Constitution and its heritage of liberty.

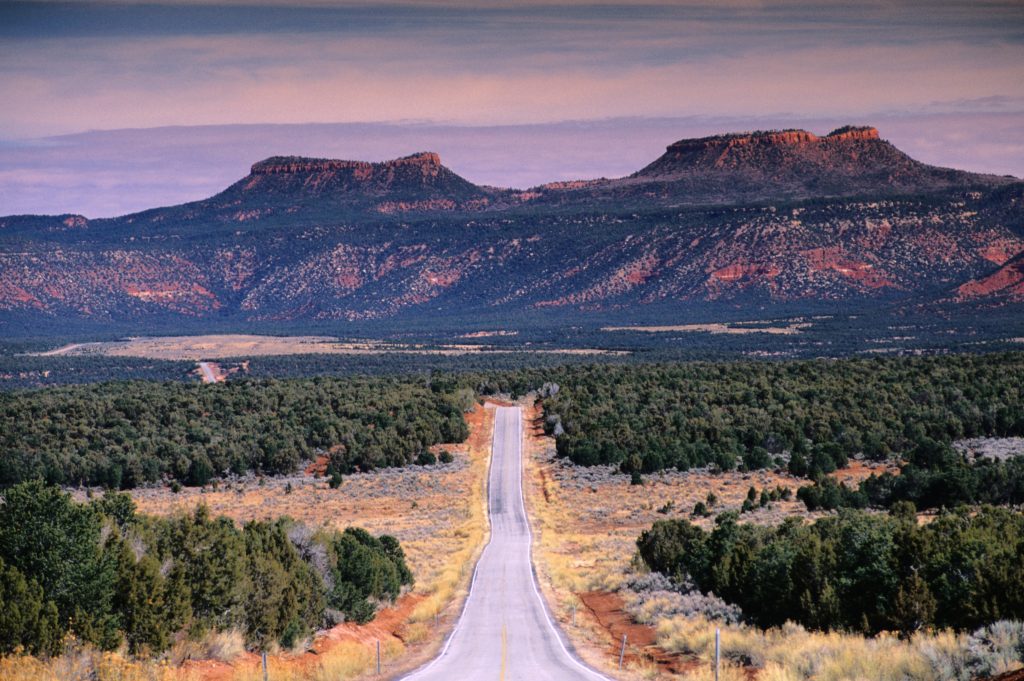

(Click on Image for a clearer view)

When, following the addition of the first Ten Amendments, Rhode Island voted to ratify the Constitution in 1790, it effectively decided the original Federalist/Anti-Federalist debate. The discussion lives on, however, and now, more than two hundred years later, we still face many of the same arguments that were contested then. The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution asserts that the states and the people reserve all powers not explicitly granted to the federal government. The Fourteenth Amendment, which was added after the Civil War, declares that no state can pass legislation infringing upon the constitutional rights of individuals, and that no individual can be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Conflicts between these two amendments make up much of the political policy debates that continue in our country today.

How does the Declaration of Independence fit into the whole scheme of things? We’ll discuss that in our next installment.

Notes of Interest: Jefferson, often classified as an anti-federalist was actuality in favor of the Constitution. He did support a bill of rights. The bill of rights were presented for consideration as amendments to the Constitution after the Constitution was ratified and the new government was put in place. In the first convening of the House of Representatives James Madison wrote and presented the Bill of Rights with the explanation that it changed nothing in the Constitution but were nothing more than explanation and clarification. Jefferson agreed but was of the opinion that these explanations and clarification were necessary in order to preserve the principles upon which they were based. Jefferson declared further that to understand the true meaning of the Constitution it must be interpreted in the understanding of those that supported it rather than by its detractors.

Good points. Several states voted to ratify the Constitution, subject to requests for specific alterations and amendments to it. In other words, their votes to ratify were contingent upon the adoption of additional amendments, ultimately including the first 10 amendments, which constitute the Bill of Rights. Those amendments were formally adopted, and later ratified, after the first United States Congress was convened. At least two of the states didn’t vote to ratify the Constitution until after the Bill of Rights had been added, and contingencies attached to several other states’ votes to ratify were not satisfied until the Bill of Rights was added.