The drop in students — nearly 300 in the last 18 years — depicts a phenomenon that they say is dampening economic opportunity and fragmenting their community’s once robust family presence.

The drop in students — nearly 300 in the last 18 years — depicts a phenomenon that they say is dampening economic opportunity and fragmenting their community’s once robust family presence.

Leland Pollock, Garfield County Commission chairman, said the county’s struggles began with the creation of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in 1996, which he said designated 93 percent of the county as federal land and ultimately led to the demise of a once rich economy built from natural resource extraction industries.

Pollock said those restrictions have reduced most job opportunities to tourism, which only attracts seasonal workers and does not appeal to family men and women. That’s why families who have lived in Garfield County for generations are splitting as their children move away in search of more opportunity, he said.

“If you lose the school, you lose the community,” Pollock said, because no family would have any desire to move to a town without a school for their children.

He said if the district closes any school, it could be the final nudge to send one of its towns tumbling over the edge of decline, which is why Pollock believes it’s the commission’s top priority to keep all of the county’s schools open.

But Escalante High School has experienced a 67 percent decrease since 1996 and is now down to roughly 50 students.

Ben Dalton, superintendent of Garfield County School District, said the dwindling student numbers are hurting programs, and three of the county’s largest high schools — Panguitch, Bryce Valley and Escalante — are now functioning under a budget that would normally operate only one.

So, the County Commission has decided it’s time to draw attention to the rural communities’ struggles and “demand help” for a problem they say they “did not create.”

The resolution passed unanimously after two public meetings last week, where Pollock said commission members heard no objections from residents.

Along with declaring a state of emergency, the Garfield County Commission “demands restoration of responsible natural resource extraction programs that support family life and the public schools in Garfield County,” according to the resolution.

Pollock said the purpose of the declaration is to draw the attention of state and congressional leaders to help drive economic development and solve public land issues.

“Before you can fix anything, first you have to identify the problem,” Pollock said. “We’ve done that. Now we have to talk about solutions.”

The first step

The resolution called for Garfield County staff to schedule a meeting within the next 30 days with officials from the school district, U. S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, the governor’s office, members of the Utah Legislature and members of Utah’s congressional delegation.

Marty Carpenter, spokesman for Gov. Gary R. Herbert, issued a statement Monday after the commission declared the state of emergency.

“We recognize there are significant challenges in Garfield County, and we are working closely with county officials and educators in the area on alternative business and education support measures,” Carpenter said. “The administration will continue to focus on bringing quality jobs despite federal regulations that have stifled the economic growth in the area for years.”

Rep. Chris Stewart, R-Utah, said he plans to meet with the Garfield County Commission within the next week to discuss the congressional action.

He said it’s not yet clear exactly what that action will be, but he mentioned a need to make federal funding for rural school districts more reliable, especially for counties like Garfield, which only have about 3 percent of land that is not federally controlled.

“I appreciate what the leadership in Garfield County is doing, and I think it’s exactly the right approach,” Stewart said.

He called the state of emergency declaration a good first step, but nonetheless a start down a long road.

“This is a generational type of a fight,” Stewart said. “But this will help us with our arguments in Washington D.C. that federal government has too much power.”

Monument impacts

However, groups like the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance have pushed to keep public lands in federal hands to prevent environmental impact or development.

“Rural towns across America are losing population, regardless of whether they are surrounded by federal land or private land,” said alliance spokesman Mathew Gross. “It seems doubtful that the future of Garfield County lies in coal, which is an industry that has been shedding jobs across the country due to mechanization and falling demand.”

But Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, said he has talked with the County Commission about state funding to sponsor a study to take a critical look at how the national monument has impacted the community.

A previous study conducted by Headwaters Economics showed protected public lands like national parks can play a beneficial economic role for rural communities. According to the study, overall population and income per capita have increased in Garfield County since the monument’s creation, and 17 percent of the county’s per capita income is attributable to the protected lands.

But Escalante’s population has declined by about 500 since the late 1990s, and the Headwaters studies did not specifically look at family size or social impacts.

Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, said in a prepared statement Monday that data deeming the national monument as an economic boon for Garfield County is “questionable at best.”

“What Garfield County is saying is these types of monuments are the root of many unforeseen damages,” Bishop said. “It illustrates why (the Antiquities Act) desperately needs reform and should no longer be used by any president as a political weapon.”

‘Quiet resolve’

Pollock said Monday’s resolution was an “honest” call for help, not a political move to advance public lands debate.

“I urge everyone to get politics out of the way and look for solutions,” Pollock said. “We need to start working right now, and we can’t be in denial.”

He said the state of emergency has already helped the county gain traction; several state lawmakers, congressional representatives and officials from the Governor’s Office of Economic Development attended Monday’s meeting.

“I am confident the pieces are in place to make this happen,” Pollock said.

Brian Bremner, the county’s public lands coordinator, couldn’t say he has “high hopes,” but instead said he has a “quiet resolve” moving forward.

“I’m wiling to face the brutal fact that we face an uphill battle,” he said. “But I’m also willing to enter that battle knowing we can prevail if we work hard.”

See previous article: Does Garfield County Have a Future?

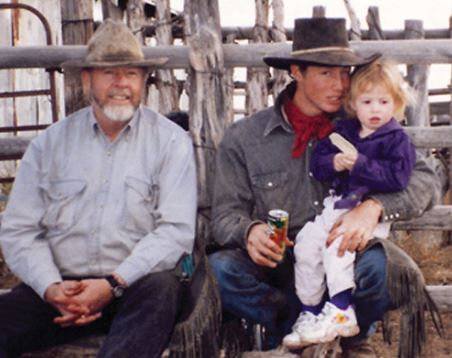

RANGE / RANGEFIRE — Spreading America’s Cowboy Spirit Beyond the Outback / Addressing Issues Facing the West

Some facts about Escalante: There are 50 govt jobs in Escalante and the number of school age kids associated with the families of those workers is 7. Each tourism job equals .2 school age children. The ranching, logging, and mining families the monument displaced had more like 2.3 kids per job. Monuments are death to a healthy community.