Time to Bite the Bullet Again

by RANGE contributor

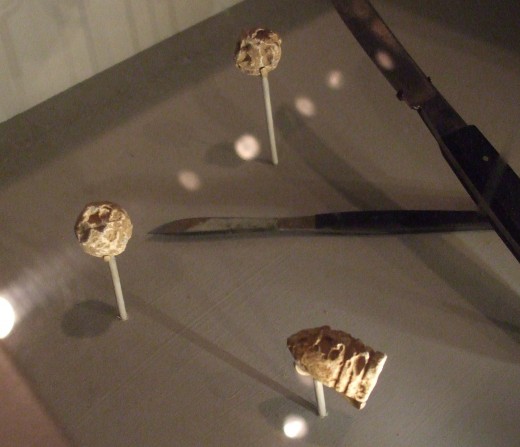

When we have to do something unpleasant, the common expression is “bite the bullet.” The phrase originated on Civil War battlefields when amputations often had to be done without anesthetics. To distract the patient from excruciating pain, he would be given a lead bullet to bite down on. Sticks or leather were common, too, but bullets were preferred because they were plentiful, and because lead’s malleability prevented breaking patients’ teeth.

Dr. Mohamed Fayed, a senior anesthesiologist at Detroit’s Henry Ford Hospital, explained a new study on the matter to the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ annual conference in Orlando, Florida. “Global warming is affecting our daily life more and more, and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions has become crucial,” he said. He lectured, “As anesthesiologists, we can contribute significantly to this cause by making little changes in our daily practice — such as lowering the flow of anesthetic gas — without affecting patient care.” Of course, no patient who has undergone surgery without anesthetics was invited to speak about whether such a decision might “affect patient care.”

Few of us would have a guessed that anesthesia would be the next target of climate activists, but Dr. Fayed pointed out, citing a 2010 study, “One hour of surgical anesthesia is equivalent to driving as many as 470 miles” in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. We all know the evils of driving our cars nowadays, so it certainly must reassure surgery patients to know they’re helping save the planet with a bit of temporary pain.

Even in the Civil War, the whole bullet-biting practice was barbaric because anesthesia had been invented several years earlier. Chloroform was administered to Queen Victoria during the birth of her seventh child, Prince Leopold, in 1853, thus popularizing the practice in obstetrics throughout Europe. Nor was the concept new even then – opium had been used as an anesthetic for centuries. Ancient Babylonians used henbane and hemlock to relieve toothaches 4000 years ago; the Chinese had practiced acupuncture as early as the Shang Dynasty; and cannabis vapors were used in India by 600 BC. Fourteenth-century Inca shamans chewed coca leaves mixed with ashes and cocaine and then spit into the wounds of patients.

The more modern approach, though, began in the early 1800s with the discovery of substances like nitrous oxide, morphine, chloroform, and especially ether. Dr. Crawford Long successfully demonstrated the use of ether on a surgical patient in 1842 and became known as the first anesthesiologist. They put him on a postage stamp in 1940, so important was his contribution to the comfort of generations of patients.

By the mid-1950s safer anesthetics like halothane began to replace ether, which is highly flammable, and chloroform, which is high addictive. Today the most common formulas include propofol, ketamine, thiopental, methohexital, etomidate, and a few other unpronounceable substances. Apparently, they are great for patients, but bad for the planet.

An article about this new study was published on the American Society of Anesthesiologists website and created an immediate Internet feeding frenzy. The headline read, “Reducing anesthetics during surgery reduces greenhouse gases without affecting patient care, study shows.” Clearly the publicity was embarrassing to the Society, because the article was removed within 48 hours after being exposed by the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow (CFACT). Several other medical news websites have also removed it.

Anesthesiologists’ entry into the global warming debate probably should not be a surprise. After all, Harvard Medical School already announced its intention to embed climate change into all aspects of the curriculum, and two years ago the American Cancer Society Journal bloviated about the “carbon footprint of cancer care.”

That article explained, “To date, no studies have estimated the carbon footprint of cancer care… The energy expenditure associated with operating cancer treatment facilities and medical devices, as well as the manufacturing, packaging, and shipment of devices and pharmaceuticals, contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions in cancer care.” If there have been no studies, then of course that entire statement is pure guesswork, or worse, an assertion motivated by a political agenda. As CFACT’s Marc Morano asked, if you needed cancer treatment, would you go to a cancer treatment center that worries about its carbon footprint, or one that worries about curing cancer?

The lead bullet metaphor is especially apt for the climate change debate. The conventional wisdom essentially holds that – no matter how much pain is inflicted on the economy by the war against reliable, affordable, and abundant energy sources – to save the planet we must all “bite the bullet” and pay whatever it costs.