By RANGE contributor and freelance journalist Marjorie Haun

Retrospective: Frederick Don Snyder KIA Vietnam, May 17, 1970

May 1970

That day in May of 1970 rendered perfect spring weather. As the lawn sprinklers beat out their lively tick, and a cloudless sky domed above my head, I twirled breezily in our backyard, dodging the spray and not minding a bit when I tumbled into the water’s path. I dried out and went inside our family home on East 2nd South to relax with my family and some cousins who had come to visit. Midafternoon brought a knock at the door, and two austere men wearing dress blue Navy uniforms stepped into our small living room. Accompanying them were more of our close relatives. One man seemed particularly tall and dignified, someone of great importance. He removed his cap and walked slowly to my mother. Before he could speak, she threw both hands around her mouth to stifle a scream, then her body buckled under the weight of some tremendous blow. Dad was beside her, greatly distraught himself, and he tried to hold her upright. Through the moans and husky sobs crowding the air I couldn’t hear what the important man had to say, nor could I understand why my mother was crying. “What happened,” I called out, but no one heard me. I asked again, more loudly, “why is Mom crying?” One of my brothers, I don’t remember which one, answered me with agonizing poise, “Don’s been killed. Don’s dead.”

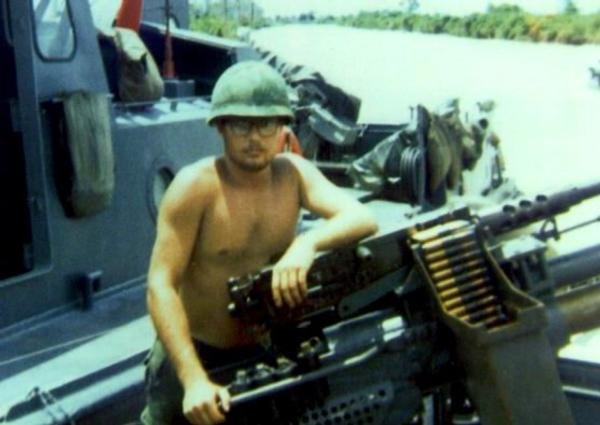

Days earlier, on May 16, as part of the Brown Water Navy, Don (Frederick Don Snyder) was on a swiftboat engaged in a three-boat troop invasion of the Dam Doi River in South Vietnam. During a patrol, while Don was at the machine gun atop his vessel, the boats came under rocket fire from Viet Cong concealed along the riverbanks. Don reacted immediately and began firing at the enemy positions. During the firefight, Don was hit by shrapnel which ripped through his chest, mortally wounding him. He was transported to the Third Surgical Hospital in Binh Thuy, and the following day was pronounced dead at the age of 22.

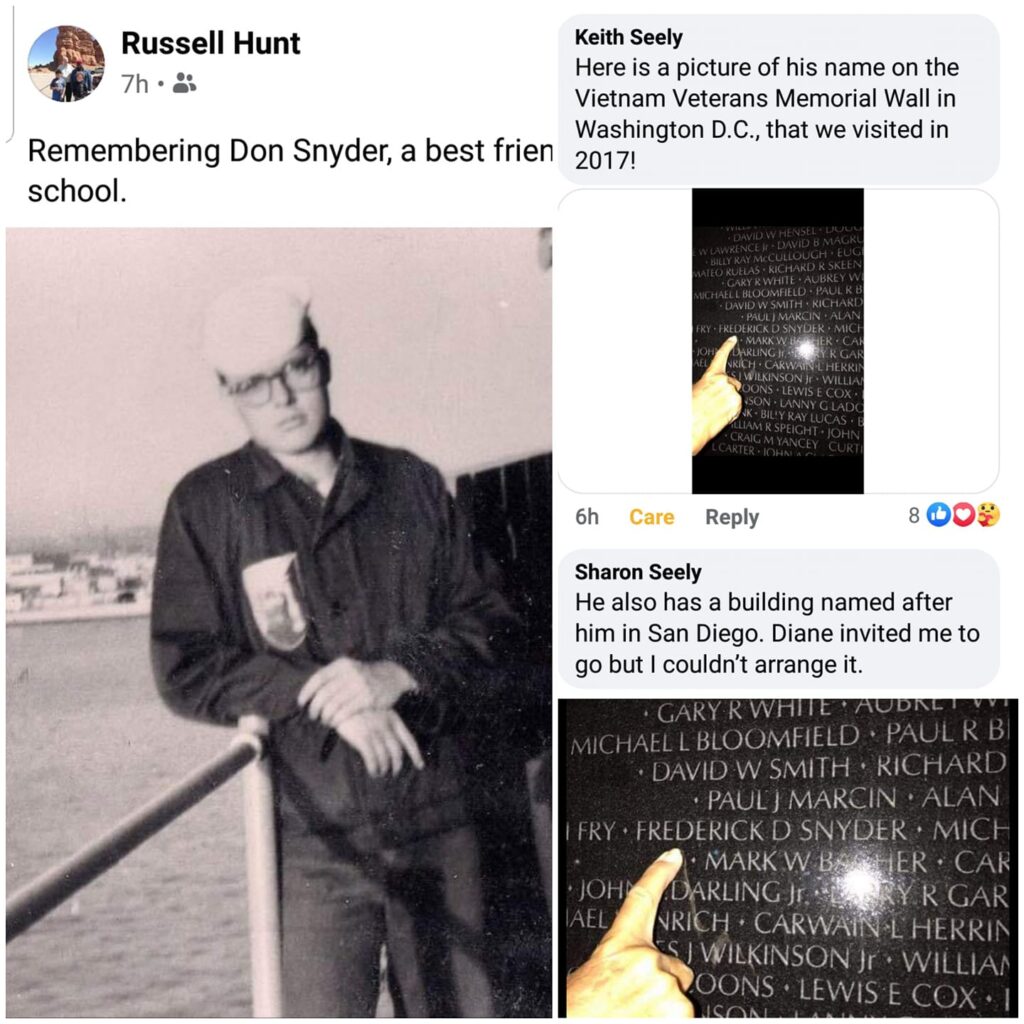

Fifty years ago, this month, the Times Independent ran Don’s obituary which read, in part: “Moab Naval serviceman, Frederick Don Snyder was killed in action in Vietnam…Son of Mr. And Mrs. Frederick R. Snyder, he was born March 6,1948 in Dragerton, Utah and was a 1966 graduate of Grand County High School. A Radarman 3rd Class, he was stationed with Coastal Div. 11 at An Thoi, Vietnam…Survivors include his parents, two sisters (Diane, Marjorie), four brothers, LeRoy, Douglas, Larry and Kevin, all of Moab.”

In exchange for his blood and his young life, the United States Navy awarded Frederick Don Snyder the Vietnam Campaign Medal, the Bronze Star with the V for Valor, the Purple Heart, and the Distinguished Service Medal. Just prior to his death, Don passed his Radarman 2nd Class test, and received a promotion posthumously.

March 1989

In February of 1989, my widowed mother, Shirley Elaine Snyder, received a letter from the Commanding Officer of the San Diego, California Naval Station informing her that Don’s name had been chosen “from a list of naval heroes who served and gave their lives for their country” to christen the station’s newest Bachelor’s Enlisted Quarters (BEQ). The Posthumous Citation awarded to Don states, “His efforts significantly contributed to the outstanding combat readiness of his craft. Coming under enemy fire on five occasions, he manned his weapon to return the attack with a highly accurate barrage of machine gun fire…His exemplary professionalism, devotion to duty and courage under fire were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

The brief Posthumous Citation omits the vital details of the story. In 2002, a man named Mike Ramsey who served with Don in the Brown Water Navy attended a Snyder Family Reunion in Paradox, Colorado. Mike told us that Don had volunteered for every dangerous mission that fell to the sailors in his division. Prior to Don’s last foray on the Dam Doi, Mike tried mightily to talk him out of taking the mission, but stubbornly he pushed out. What’s more, according to my brother Kevin, one of the casualty officers who came to our home in May of 1970 explained that Don had been manning the 50-caliber gun atop the lead boat that took the disabling rocket hit. The blast that sent shrapnel through Don’s chest also knocked him off the machine gun perch to the bottom of the ladder. In spite of his dire injuries, he crawled back up the ladder, remounted the 50-caliber gun and took out the enemy position, saving the men in his crew.

In Don’s memory and for his valor, Snyder Hall, a 12-story dormitory built to house nearly 900 enlisted personnel, was dedicated on what would have been his 41st birthday, March 6, 1989. The entrance of the BEQ is decorated with replicas of Don’s medals and Navy plaques.

The Pilgrimage

In late 2010, my oldest living brother, Leroy, received a call from a man named Peter Dekker who served on the USS Towers with Don from 1968 to 1970. The Towers, a guided-missile destroyer, was stationed off the coast of Vietnam as part of the New Jersey Battle Group. Peter, who made his home and life in New Hampshire, had wanted for many years to come and visit Don’s grave. Myself, my brother Leroy and his wife, Tina, arranged to meet up with Peter on January 30, 2011. When Peter entered Leroy’s house that day, his eyes immediately filled with tears and his first words were: “I’ve been needing to do this for 41 years.”

Peter at the time was in his early sixties, stout but fit, tanned with a full head of salt and pepper hair pulled back into a Jeffersonian ponytail, and an elegant goatee. He spoke with great emotion, recalling his years on the USS Towers with Don. He spoke of Don’s intellect and headstrong temperament. They were both radarmen, working in closed quarters and executing tasks that required focus and sensitivity. The most difficult recollection for Peter was when Don transferred from the relative safety of the ship to the Vietnamese mainland. Peter intimated that their Commanding Officer disliked Don and the friction between them had become intolerable. Perhaps in a moment of anger or frustration Don opted to go with the Brown Water sailors, and that became the irreconcilable moment for his friend. Peter stayed on the Towers, served out his term, returned home to his wife, raised a family and made a successful life as a horticultural designer in New Hampshire. Don left the safety of the open sea, took up the machine gun on a swiftboat, and returned home to Utah at the age of 22 in a flag-draped casket.

Peter and I still keep in touch. Each year on Veteran’s Day and Memorial Day he sends me a message, always with the encomium, “Your brother is not forgotten. Love, Peter.” Peter is retired now and flys general aviation as a hobby. He wants to fly out to Utah with his wife someday to visit. I hope he does.

Post Script

The poignancy of Don’s story is in the stolen years he should have spent as a man, a husband, a father, a son, a brother, a friend. The young should never die. Parents should never have to bury a child. But it is a swift boat that takes us down the river of life, and the young die, and parents too often say untimely goodbyes to their darling sons and daughters. Buildings, medals and recognitions are insufficient to heal wounds taken in war, but Don’s surviving siblings, nieces and nephews, and grandnieces and grandnephews, are grateful that he is not forgotten, and that he is loved. As for me, his little sister, I am grateful for his buddies, men such as Mike Ramsey and Peter Dekker, who like Don, marched headlong into a foreign war that made no sense and promised little other than humiliation upon the return home. To those men and women who served and fought and died during the Vietnam War, you are not forgotten. You are loved.

# # # # #

1 thought on “Brown Water and My Brother’s Blood”