Note: If you haven’t read the piece — Making Rain Where the Sun Shines – the Making of a Country Lawyer — you might want to read it before this piece.

In every law firm, every office, every town, no matter how big or small, there are interesting politics, reactions and interactions between personality chemistries. Overall, Kanab seemed to have at least its fair share of such chemical reactions. In the small Kane County legal community, as already alluded to, there was a long-standing blood feud between Tim Stankey and Marsha “Shay” Alexander.

In every law firm, every office, every town, no matter how big or small, there are interesting politics, reactions and interactions between personality chemistries. Overall, Kanab seemed to have at least its fair share of such chemical reactions. In the small Kane County legal community, as already alluded to, there was a long-standing blood feud between Tim Stankey and Marsha “Shay” Alexander.

Shay Alexander had been the Kane County Public Defender at times, so there had apparently been plenty of call for interaction between her and Stankey over the years, and she still had the Kanab City Public Defender contract when I arrived in Kanab. Although I never really did learn or understand the exact origin of the bad blood between them, Alexander and Stankey were essentially mortal enemies.

Based on the escalating contention between them, Stankey had apparently filed a bar complaint against Alexander based on some kind of trust account impropriety, having to do with how funds from a settlement were handled. I don’t know how serious the impropriety was, but if there is one thing state bar associations take very seriously, it is trust account handling and accounting. In any event, Stankey’s complaint ultimately led to a bar investigation and temporary suspension of Shay Alexander’s license to practice law. In the meantime, She and her sister wives started publishing a small weekly rag called the Big Water Times (with it’s catchy subtitle “the best little paper by a dam site,” referring to its proximity to the Glen Canyon Dam, just outside Page, Arizona), in which they absolutely crucified Stankey on a regular basis. The Times’ regular attacks on Stankey, as well as Kane County Commissioners Al Pompum and Garth Madsen provided some of the most popular and entertaining reading in all of Southern Utah. All other local papers paled by comparison.

Because Shay Alexander had the Kanab City public defender contract at the time of her suspension, however, until they found a new public defender, the Kanab City Council asked if I would be willing to fill-in on a temporary basis, and handle any cases involving indigent defendants, that would have otherwise been assigned to her. Because I felt some ethical obligation to help out in that regardt, and had been similarly appointed in several cases in district court, I agreed to stand in on a temporary basis until a more permanent arrangement could be made.

These cases were in the Kanab City Justice Court, before the honorable Patrick “PC” Chapman. Although I had already developed concerns about most lay justice court judges in general; and although Judge Chapman was a friend of Maggie Rawlins; I had developed serious, specific concerns and reservations about Judge Chapman.

Now, just to clarify, like many lay justice court judges in Utah (but unlike Judge Paula Hamblin, the Kane County Justice Court Judge), Judge Chapman had never been a lawyer, never been to law school, had very minimal legal training, and exactly what his qualifications were to be a judge, I’d never quite been able to figure out — and how he got the job I’ll never know.

One of the things that struck me quite odd about Judge Chapman was that a considerable number of fairly unsavory characters just seemed to gravitate to, and hang-out around his office. They would typically be defendants, who had appeared in his court on criminal charges, along with all their family and friends. As a general rule, in addition to any fines or pecuniary penalties he might impose, he would typically also put them on bench probation, requiring them to report personally to him on a regular basis. When they went to report, he would listen to them, be friendly, empathize, commiserate, be-friend them, and before you knew it, they and their friends and family would be flocking to his office just to visit, or ask for free legal “advice” – talk about a good way to maintain impartiality.

One of the things that struck me quite odd about Judge Chapman was that a considerable number of fairly unsavory characters just seemed to gravitate to, and hang-out around his office. They would typically be defendants, who had appeared in his court on criminal charges, along with all their family and friends. As a general rule, in addition to any fines or pecuniary penalties he might impose, he would typically also put them on bench probation, requiring them to report personally to him on a regular basis. When they went to report, he would listen to them, be friendly, empathize, commiserate, be-friend them, and before you knew it, they and their friends and family would be flocking to his office just to visit, or ask for free legal “advice” – talk about a good way to maintain impartiality.

Instead of being a typical magistrate, Judge Chapman was more like an amateur, unlicensed lawyer in a legal aid office, probation officer and guidance counselor all rolled into one. I used to say that he was the most oft-quoted, wannabe attorney in town, and the state bar ought to investigate him for unauthorized practice of law — from his judicial chambers no less.

But, regardless of what I thought, word spread; the defendants told their friends, and they told their friends. All of which made Judge Chapman quite popular. Maybe it was just professional jealousy, but for a while, it got to the point that any time a legal issue or question would arise, people — especially a certain element — would run to Judge Chapman for advice. He didn’t seem to have any reservation about sharing his opinion, as if it were the gospel, on just about any matter of legal consequence, whether he had a clue what he was talking about, or not.

For quite a while, Maggie Rawlins became one of Judge Chapman’s would-be clients. Maggie would go see Judge Chapman about everything from problems she was having with the BLM, to how she could go about legally doing away with her neighbor, Cliff Mayhew. Then she’d come tell me what Judge Chapman had told her, and see what I thought of his advice. I guess she was just making sure she had a second opinion. Most of the time I would just roll my eyes and tell her that I thought Judge Chapman ought to try to focus on being a judge, instead of trying to be an uneducated, unlicensed, inexperienced free legal know-it-all. As a general rule, to me, his advice usually seemed rather ill-founded, and way over his head.

Moreover, based on this pattern, one of my biggest concerns was that the concept of judicial decorum simply didn’t apply to Judge Chapman. Rather than hold himself above or apart from the general populous and the people who appeared before him and/or attempting to command any degree of respect, like most judges do, Judge Chapman was more than willing to treat just about everyone, but particularly convicted defendants on probation, like bosom buddies. When people came away from his office, describing his advice, it was never “Judge Chapman says this” or “Judge Chapman said that,” it was always “PC says this” and “PC says that.” Obviously, most defendants who appeared in his court came to feel like they were on a first name basis with the judge. When defendants in his court were describing the necessity of going to see him pursuant to their bench probation, it was never “I’ve got to go see the judge” or “Judge Chapman.” It was always “I’ve got to go see PC.”

You’d think all of this would bode well for a criminal defense attorney appearing in his court, but it didn’t. Like most lay justice court judges, Judge Chapman was quite defensive about attorneys, and seemed to have a strong dislike for attorneys generally, especially criminal defense attorneys, and would obviously have much preferred to do his job without them. When it came to criminal defendants, he always seemed to want to convict them first, apparently to add them to his circle of friends.

When I was trying cases in Judge Chapman’s court, it soon became obvious to me that he seemed to believe every word that crossed a police officer’s lips, and during a trial he acted as if the prosecutor was leading him around by the nose. This might have had something to do with the fact that his office and the city police office were right next to each other. Plus, that’s where Darrel Snow, the city attorney, usually hung out when he was in town. So obviously, in addition to all being on the same pay roll, they all kind of hung out together, and ate cake and ice cream for each other’s birthdays. So, it probably shouldn’t have been any major surprise when, in court, Judge Chapman would grant virtually every prosecution objection, and rule according to every argument or assertion made by the prosecution, as if directed from above. Consequently, as a general rule, working in his court as a criminal defense attorney was a very frustrating experience.

Nonetheless, I agreed to help out and handle the indigent defense cases until they could get a new public defender appointed. Because most of the cases in the Kanab City Justice Court involved minor matters like traffic violations, I only had two cases assigned before they appointed a new public defender, but they both left their marks.

Nonetheless, I agreed to help out and handle the indigent defense cases until they could get a new public defender appointed. Because most of the cases in the Kanab City Justice Court involved minor matters like traffic violations, I only had two cases assigned before they appointed a new public defender, but they both left their marks.

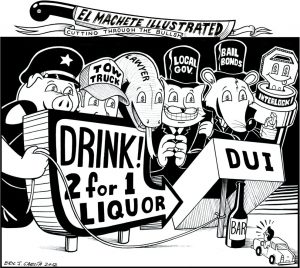

The first case involved a DUI charge against an old cowboy by the name of Ted Lindenhof. Ted was a good old ranch cowboy. The kind that there are increasingly few of, especially in this part of the country; the kind that just kind of drift around, working on one ranch for awhile, then moving on to work on another. It is increasingly difficult for those kind of cowboys to find good work, and most people these days seem to need more security than that kind of life offers.

Ted’s sole physical possessions consisted of his outfit (saddle, chaps, spurs and horse gear); his clothing, bedroll, and an older model Dodge van. He had the van set up pretty well, with a bed, a small heater, water tank, fridge, stove, etc., so that he could just live in it if and when he needed to, between jobs. Ted was old enough that he was drawing social security. Between his social security, and the cowboy wages he could draw, along with some room and board, here and there, he got along pretty well. Perhaps more importantly, he enjoyed it, and he was free as the wind.

When I met him, Ted had been cowboying in Wyoming for the summer, and as the seasons changed and it started getting colder, he had decided to drift south to Arizona, to look for a job, and spend the winter. With his social security, he could actually survive and get by just living in his van, if he had to, but he sure didn’t want to have to spend a cold, windy Wyoming winter that way. So he was passing through Kane County, on his way south to Arizona.

Like a lot of good old cowboys, Ted didn’t mind a having a drink now and then, and had bought himself a bottle to help keep him company as he was driving south. He figured he’d drive as far as he could get, then just pull over and spend the night. But by the time he crossed into Kane County and hit Long Valley, he had pretty much emptied the bottle, and had a fairly suspicious driving pattern. Several people had noticed his erratic driving, and reported it to the Kane County Sheriff’s dispatch. By the time they tracked Ted down and caught up with him, he was almost to Kanab.

A Kanab City police officer stopped Ted just as he was coming into town.

“Good evening sir, how’re you doing this evening?” the officer asked, as he stuck his head in the window and was virtually overcome with the smell of alcohol.

“Jussssfine. How’r’you occiferrr?”

“Oh, well, I’m doing just fine too. Do have any idea why I stopped you?”

“Well, noddd, nod really. Ah thing everrr’think worgs, and ah know ah wasssn’ speeding.”

“Have you had anything to drink?”

“Me? Driinng? What mayges you thing ah’ve had anathink to dring?”

“Oh, I was just wondering, first by the way you were driving; second by your breath and the way you’re talking, and third by the smell of alcohol in your vehicle. . . . Would you mind stepping out and doing a few simple field sobriety tests for me?

“You mean tougje my finger with my nossse?” Ted said. “I can tougje my finger with my nose,” and started reaching for his nose.

“Why don’t I have you get out to do it; I’d like to have you step right over here and take a little walk for me.”

So Ted stumbled out, and like the good sport that he was, tried to perform the officer’s field sobriety tests.

“Well, Mr. Lindenhof, what would you think about taking a little ride with me in my patrol car over to the sheriff’s office? I’d like you to take another test. We’ll lock up your vehicle so everything will be nice and secure until we get back.”

For his winning score of 1.9, more than twice the legal limit of .8, on the Intoxilyzer, Ted Lindenhof won free room and board in the county jail — until he could bail out.

Because Ted was apprehended in town, his case was within the jurisdiction of the Kanab City Justice Court, where he was charged with DUI (second offense), open container, expired registration, and no insurance. He appeared before Judge Chapman for an initial appearance, and he assigned the case to me, because he found Lindenhof to be indigent.

Because Ted was apprehended in town, his case was within the jurisdiction of the Kanab City Justice Court, where he was charged with DUI (second offense), open container, expired registration, and no insurance. He appeared before Judge Chapman for an initial appearance, and he assigned the case to me, because he found Lindenhof to be indigent.

I went to visit Ted at the jail, and we hit it off right away. I kind of told Ted what was going on, what he was charged with, explained his rights, and outlined some options. The DUI second offense made the charges pretty serious.

Ted told me his situation.

“Well, I was plannin’ on winterin’ down ‘round Yuma,” he said. “Down where it’s warmer, so’s if I can’t find a job, I could just live in m’ van, ‘n get by fairly comfortable on m’ social security, til Spring.”

“So I guess we better see if we can get you out of here, and on your way then.” I responded. “Could you come back for a trial if you need to?”

“What’s it gonna take t’ get me outa here?

“It’s just a matter of bailing out. It’s a $2200 cash bond, or you could probably get a bail bondsman to bail you out for about $300.”

“What ‘bout m’ van? There’s no point a me gettin’ out, if I’m agonna be afoot.”

“Yeah, you’ll have to pay the towing and impound fee to get that out. Then it looks like they’ve got you charged with expired registration and no insurance, so you’ll have to take care of all that too.”

“How much’ll it all be?”

“Oh, I don’t know, probably around $100 for towing and impound, and I’d guess probably around another hundred and fifty or so to get your outfit legal, if there’s nothing that needs to be fixed.”

“So that’d be around $550, at least, just t’ get me outta here ‘n on the road again, huh?”

“That’s what it looks like.”

“Well, I’ve only got a couple, say three hundred dollars, t’ m’ name. I guess I could hawk m’ saddle ‘n outfit, but I kinda hate t’ do that.”

“Yeah, I’d hate to see you do that too.”

“Ya know, t’ be perfectly honest,” Ted said, “this place just ain’t all that bad. I kinda hate t’ be locked up like this ‘n’all, but at least it’s warm; the grub’s good, even better’n I expected, and certainly better’n m’own cookin’. There’s a TV, ‘n people ‘round t’ visit with. I can even go outside ‘n exercise ‘n get a little fresh air everday, if I want to. It’s really not that bad. What’d’ya think the chance’d be of just kinda stayin’ on an’ winterin’ right here?”

“Ya know, t’ be perfectly honest,” Ted said, “this place just ain’t all that bad. I kinda hate t’ be locked up like this ‘n’all, but at least it’s warm; the grub’s good, even better’n I expected, and certainly better’n m’own cookin’. There’s a TV, ‘n people ‘round t’ visit with. I can even go outside ‘n exercise ‘n get a little fresh air everday, if I want to. It’s really not that bad. What’d’ya think the chance’d be of just kinda stayin’ on an’ winterin’ right here?”

“Well, I don’t know, I’d never thought of that. I’m usually trying to get people out of jail, not keep them in. I guess I could try to continue and delay things as much as possible, and try to buy you a couple months in here. Are you sure that’s what you want to do?”

“Well, it’s at least ’s good ’s any other prospects I’ve got right now. M’ livin’ expenses would be nexta nuthin’ and I could save up some social security t’ get m’ van goin’ agin, ‘n be ready t’ go come Spring.”

“Let’s see, it’s November 29th; how long you figuring on trying to stay in here?”

“Well, if I could leastways make it into February, ‘long toward March, I oughta be in pretty good shape. I guess a whole lot’d depend on how long it’d take me t’ save up what I’d need t’ get m’ van out, ‘n see what th’ weather’s doin’ b’ then.”

“Yeah, and one problem is that your van continues to accrue impound fees at the rate of about $5.00 a day. So it’s going to cost at least $150 a month, just to let it sit there. And that’s on top of what you already owe.”

Because Lindenhof was incarcerated, his case received expedited preference for trial. When the Court called to try to schedule the trial, I thought up and concocted every possible scheduling conflict I could possibly think of to get it put off until December 23rd.

Of all the various kinds of cases handled by the Kanab City Justice Court, it seemed like only the alcohol-related ones were generally serious enough to justify appointment of a public defender. So the other appointment I received about the same time was the defense of Larry Begay and Jim Manymules on DUI  charges. I could tell by their names and the Kaibeto, Arizona address on the charging documents that they must be Navajos from the reservation, which can create some real interesting communication and other legal challenges. To help me track them down, I assigned Nan and Marshal Ike Ballard the task of helping me locate them and establish communication. Ike was the Fredonia Town Marshal, a good friend of mine, and had been quite effective in tracking down people on the reservation for service of process in collection cases. I was always amazed at Nan’s connections, who she knew, and her ability to make just about anything happen, so I figured between the two of them, they’d track down our clients.

charges. I could tell by their names and the Kaibeto, Arizona address on the charging documents that they must be Navajos from the reservation, which can create some real interesting communication and other legal challenges. To help me track them down, I assigned Nan and Marshal Ike Ballard the task of helping me locate them and establish communication. Ike was the Fredonia Town Marshal, a good friend of mine, and had been quite effective in tracking down people on the reservation for service of process in collection cases. I was always amazed at Nan’s connections, who she knew, and her ability to make just about anything happen, so I figured between the two of them, they’d track down our clients.

After putting out a few feelers, they came back with the news that when they were around, these particular Navajos worked for Jens Sherman, a Fredonia rancher, but according to Jens, he didn’t really need them much during the winter, so this time of year they would often be gone for months, and then just show up again in the Spring. The long and the short of it was that he didn’t really know how to get a hold of them. But in my one and only subsequent run-in with Jens, he let me know in no uncertain terms that I better take care of his Navajos and keep them out of jail.

According to the police report, there had been three people in the car. Jim Manymules, Larry Begay, who was Jim’s step-son, and Ruth Manymules who was Jim’s wife and Larry’s mother. They had come flying into town in a Ford half-ton pick-up, with Big Jim behind the wheel, as personally witnessed by at least one off-duty officer as he saw them pass. They skidded into the Frost-Top Drive-Inn parking lot, and didn’t shut the truck down in time to avoid bouncing its front tires up over the cement parking barriers, and almost right on through the building. It took some doing for them to finally get the pickup lifted up and pushed back over the cement barriers, into the parking lot. By the time that was done, several officers had arrived to see if they could lend a hand, and check their sobriety.

According to the police report, there had been three people in the car. Jim Manymules, Larry Begay, who was Jim’s step-son, and Ruth Manymules who was Jim’s wife and Larry’s mother. They had come flying into town in a Ford half-ton pick-up, with Big Jim behind the wheel, as personally witnessed by at least one off-duty officer as he saw them pass. They skidded into the Frost-Top Drive-Inn parking lot, and didn’t shut the truck down in time to avoid bouncing its front tires up over the cement parking barriers, and almost right on through the building. It took some doing for them to finally get the pickup lifted up and pushed back over the cement barriers, into the parking lot. By the time that was done, several officers had arrived to see if they could lend a hand, and check their sobriety.

According to Judge Chapman, if I could ever get them back to court, we’d have a trial. Otherwise, he said he intended to proceed in “absentia,” and try them based on the evidence available. I told him to give me some time; that based on the information I’d gotten, we might be able to track them down and get them back to town along toward Spring.

You may also like

-

Between Fences and Firearms, Part 2 — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Between Fences and Firearms — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Cow Lawyer — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Real People for Clients — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod

-

Making Rain Where the Sun Shines — the Making of a Country Lawyer — Range Wars & Legal Tales — by Mancos MacLeod