This article by the late Dr. Michael S. Coffman was originally published in the Summer 2015 edition of RANGE magazine. Everyone at RANGE magazine, and our readers, sorely miss Dr. Coffman and his timeless insights and scientific reports. We hope you will enjoy this fascinating and enlightening article. ~Ed

Magna Carta

The 800-year road to freedom. Most of the historic documents dealt with the rights of private property. By Michael S. Coffman, Ph.D.

“Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”—Variously attributed to George Santayana or Edmund Burke

Most people are bored with history. Some history, however, controls our lives today. Eight hundred years ago the seed of freedom and prosperity began to take root in England. You’d never recognize it from the powerful set of principles that were eventually engrafted in the Constitution of the United States, but it was a unique beginning. It is considered to be the first constitution ever written in Europe.

Until 1215 the world was ruled by tribal chiefs, despots and kings who generally had undisputed power over everyone. However, when King John signed the Magna Carta at Runnymede, an agonizingly slow process was born that gave us the freedoms we have today.

Written entirely in Latin, the Magna Carta (“Great Charter”) was born after years of strife and civil war between the feudal nobility and King John in England. Just like so many kings before him, John abused his powers. Under the feudal system, the nobility had to provide the money and manpower for the king to raise armies to conquer land. Portions of France were already under English control and the nobility had to cover the costs of an army to protect and administer it.

In addition to barons providing the men for armies, kings historically consulted the barons before raising taxes. King John, not so much. He was forever demanding more taxes and men. In 1204, John lost the conquered land in northern France and immediately demanded even higher taxes without consulting the barons. At the same time he challenged the authority of Pope Innocent III, and in 1208 became the first sovereign to be excommunicated by the Catholic Church. All church services were also banned in England, raising the ire of all citizens. It wasn’t until 1214 that John relented and accepted the power of the Catholic Church.

After being defeated by France once again in 1213-14, John demanded “scutage” (money paid in lieu of military service) from the barons who had not joined him on the battlefield, much to the outrage of the nobility. Meanwhile, Stephen Langton, archbishop of Canterbury, successfully channeled baronial unrest to put increasing pressure on the king to make concessions.

King John finally agreed to the archbishop’s concessions, but when negotiations stalled in early 1215, civil war broke out and John’s longtime adversary, Baron Robert FitzWalter, gained control of London. Backed into a corner, King John yielded on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede beside the River Thames. He accepted the terms in a document called the Articles of the Barons. A final version written in Latin was issued four days later that would be renamed the Magna Carta.

The original Magna Carta in 1215, written in Latin. Although the document had many defects, further improvement allowed the common man to own property, which allowed England to develop a middle class and become the wealthiest nation on earth with a vast Empire. Photo: Public Domain

Of the 61 clauses or chapters in the Magna Carta, most dealt with property rights. Nine chapters played a central role when America’s Founders wrote the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. These ranged from the protection of the Church, to the right of petition, freedom from forced quartering of troops, unreasonable searches, trial by jury, cruel and unusual punishment, to the most important, due process of law and property rights.

For instance, Chapter 39 of the Magna Carta states: “No freeman shall be arrested, or detained in prison, or deprived of his freehold [property], or in any way molested; and we [the King] will not set forth against him, nor send against him, unless by the lawful judgment of his peers by the law of the land.” Habeas corpus, rule of law, freedom from search and seizure, trial by jury, legally protected private property rights in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights all come from that chapter.

King John apparently could not accept defeat and reneged on several key provisions. Three months after he signed it, civil war once again broke out. Following the death of John in 1216, the advisors of his successor, nine-year-old Henry III, reissued the Magna Carta. It was reissued again in 1217 and 1225 with modifications.

In the 1225 revision, Chapter 39 of the 1215 version of the Magna Carta became Chapter 29: “No freeman shall be taken, or imprisoned, or be disseised of his freehold [old English for depriving a person of his property] or liberties, or free customs, or be outlawed, or exiled or any otherwise destroyed; nor will we [the King] pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either justice or right.”

As Chapter 29 of the 1225 Magna Carta shows, the various revisions and updates to the Magna Carta served to strengthen the rights of individuals, especially their private property rights.

From 1225 to 1690

The rights guaranteed in the Magna Carta were threatened in the early 1600s when King Charles I broke up Parliament and ruled England on his own. His decrees denied Englishmen due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines.

In response, Parliament wrote the Petition of Right in 1628. Like John in 1215 when he accepted the Magna Carta, in 1628 Charles I initially accepted the Petition of Right. He had to in order to continue the brutal 30 Years’ War that devastated Europe.

The Petition of Right imposed restrictions on the king’s ability to levy abusive taxes, forced billeting of soldiers, imprisonment without cause, and the use of martial law. Also like John, Charles I soon broke his word and resumed his authoritative rule. As with John, civil war broke out, ending with the beheading of Charles I in 1649. The nobility’s property rights were not to be trifled with. Charles I was succeeded by Charles II, who ruled until his death in 1685.

The Habeas Corpus Act was passed by Parliament in 1679 as the Magna Carta evolved. Both the Petition of Right and the Habeas Corpus Act were based on Clause 39 of the original Magna Carta: “no free man shall be…imprisoned or disseised…except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” They were also based on Clause 40 which states: “to no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.” Like the Magna Carta, both documents played a central role in the writing of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

There was one more major bump in the English road to liberty. By 1685, King James succeeded his brother Charles II when Charles died. James was a Catholic and began invoking laws favorable to Catholics, ignoring the Protestant Parliament. When James positioned a part of his large army near London, Parliament feared it might be a prelude to James claiming all power for himself, just as his father Charles I had done.

King James’ daughter, Mary, fortuitously happened to be a Protestant. She was also in line for the throne, once removed by her much younger brother. She had previously married William of Orange, a Protestant prince in the Netherlands. Parliament invited William of Orange to invade England. Called the Glorious Revolution, William had the Protestant English citizenry on his side and easily won the war in 1689. Parliament invited William and Mary to become king and queen. They accepted, albeit with certain restraints called the English Bill of Rights—which made sure that the monarchy could never again do what James had done. If the king or queen wanted to raise taxes or keep a standing army, they had to get the permission of Parliament. Not surprisingly, the English Bill of Rights was based upon the now much revised Magna Carta. It contained important provisions by which the monarchy lost any absolute powers it may have retained in the 1215 Magna Carta. With it, England became a “constitutional monarchy” in which the monarch was the official head of state but the real power was in the elected Parliament.

Again, the English Bill of Rights played a central role in creating the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. That is especially true of the separation of powers. America’s Founders were acutely aware that if there was any opportunity for the king to take power from the legislative branch, sooner or later he will make the attempt. It is human nature. That led the Founders to create the tripartite system upon which the Constitution rests: legislative, executive and judicial.

Three Influential Philosophers

Initially the provisions of the Magna Carta were only granted to the nobility. Of its 63 clauses, many were concerned with the various property rights of barons and other powerful citizens. The common citizen still had no voice in government and had no property rights. That changed in the late 1500s when Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) wrote that all men should have the right to own legally protected property.

It was Sir Edward who wrote and then presented the Petition of Right passed by Parliament to Charles I in 1628. Sir Edward then established an independent judiciary in England that reinforced the basis of three equal branches defined in the U.S. Constitution.

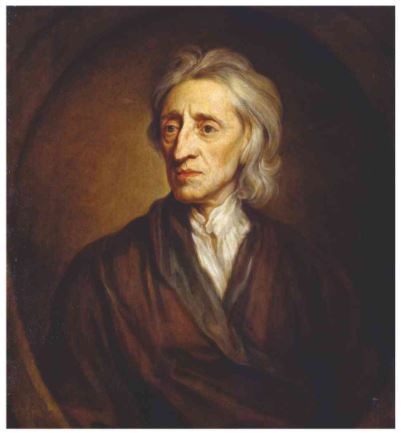

John Locke (1632-1704) followed on the heels of Sir Edward Coke. Locke studied medicine at Oxford where he received a bachelor of medicine in 1674. He was also a philosopher and prolific writer and laid much of the groundwork for the Enlightenment. He made central contributions to the development of scientific empiricism and true liberalism (not to be confused with the hijacked concept by “leftism” in today’s American politics). Locke’s greatest contribution was to build a more thorough rationale for private property rights and government from the foundation of the Magna Carta.

Locke’s “Two Treatises of Government” was initially ignored in England but eventually provided the foundational thinking of the American Founding Fathers. His theory of limited government by the consent of the governed and nature’s law of “life, liberty and estate” deeply influenced the American Founders and played a central role in the framing of our founding documents—especially the Declaration of Independence.

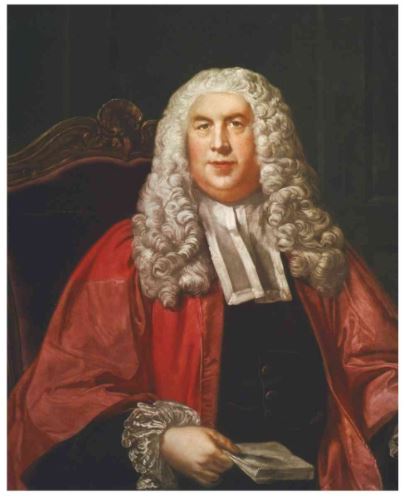

While “Two Treatises of Government” provided the foundational principles of the United States, it was Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780) who provided the foundation of American law. Like Sir Edward, Sir William was a prolific writer, a member of Parliament and jurist, eventually becoming a judge. While all three philosophers were extensively cited by our Founding Fathers, it is Sir William Blackstone and his “Commentaries on the Laws of England” that revolutionized English and American law.

Sir William’s longest volume was the “Right of Things,” which dealt with property rights. In it, he emphatically stated: “The third absolute right, inherent in every Englishman, is that of property: which consists in the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of all his acquisitions, without any control or diminution, save only by the laws of the land. The laws of England are therefore, in point of honor and justice, extremely watchful in ascertaining and protecting this right.” Sir William based his legal theories on the Magna Carta as refined by Sir Edward Coke, John Locke and other lesser known British philosophers of the day.

Sir William’s “Commentaries” provided the legal backbone to most of our founding documents in general, and the U.S. Constitution specifically, so much so that they rank second only to the Bible as a literary and intellectual influence on the history of American institutions. More importantly, for well over a hundred years the U.S. Supreme Court depended heavily upon Sir William’s “Commentaries” in deciding constitutional law. That changed as 20th century progressives attained positions of power within the judiciary system and moved away from Sir William’s civil liberty foundation to a much more socialist view of law.

Property Rights

It is staggering how the public education system in America has revised history so much that Americans no longer even recognize the names of Coke, Locke and Blackstone, let alone that their writings form the basis of our liberties. Worse, most Americans think property rights are not all that important, when in fact they are the most important right we have. There is a reason for this.

Bernard Siegan, distinguished professor at the University of San Diego Law School, did an exhaustive review of history and law from the Magna Carta through recent history. In his book, “Property Rights: From the Magna Carta to the Fourteenth Amendment,” Siegan takes the reader step-by-step through history in one of the best documented analyses of our legal roots in modern times. He exhaustively reviewed key state, federal and Supreme Court decisions during the first 80 years of the United States. His detailed review proves progressive commentators apparently “overlooked” a mountain of case law that shows that the protection of private property rights was central to almost every decision made by the various courts during those first 80 years. More than that, he found that there was a “remarkable consistency between the rulings of state and federal judges. Virtually all [court decisions] supported the requirement of just compensation to validate a nonconsensual government acquisition or occupation of private property.”

These U.S. court decisions cited Sir Edward Coke, John Locke and Sir William Blackstone. Our Founding Fathers made it crystal clear that well-protected property rights are the foundation to life, liberty and the creation of wealth. James Madison was so convinced of the importance of property rights that he wrote: “Government is instituted to protect property of every sort; as well as that which lies in the various rights of individuals…this being the end of government, that alone is a just government, which impartially secures, to every man, whatever is his own.”

The importance of private property rights was a central tenet freely and often discussed amongst all the citizenry. Alex de Tocqueville, the French scholar and political commentator, traveled through America studying its culture and law from 1831-1832. He confirmed: “In no other country in the world is the love of property keener or more alert than in the United States, and nowhere else does the majority display less inclination toward doctrines which in any way threaten the way property is owned.”

The Loss of Property Rights

So how did U.S. law get so perverted that the government can now dictate to private citizens how they use their property? Our government replaced the real history revealed by Siegan with socialist revisionism in school textbooks and alleged “scholarly works.” Progressive revisionism has been standard for nearly 100 years. Progressivism is based in emotionalism, and school textbooks and media almost always focus on how common use of property (like other people’s paychecks) benefits all people.

As we’ve described in numerous RANGE articles over the past years (see footnote), the EPA is one of the worst offenders. It is attempting to control all property rights through a host of draconian regulations that are supported by little to no science: the war on coal(1), expansion of water jurisdiction(2), global warming(3), green energy(4), Agenda 21(5), and rampant corruption(6). All destroy private property rights and state sovereignty by centralizing control in Washington, D.C.

It would be wise to heed the warning of Thomas Jefferson in 1821: “When all government, domestic and foreign, in little as in great things, shall be drawn to Washington as the center of all power, it will render powerless the checks provided of one government on another and will become as venal and oppressive as the government from which we separated.”

Jefferson was not a prophet. He merely understood human nature and how it would corrupt the intent of the Constitution over time. Ask yourself: What constitutional provision authorizes asset forfeiture, even when the person has not been charged with a crime? Where in the Constitution does it allow a federal agency to usurp jurisdiction over nearly every drop of water in the United States? What constitutional provision allows President Obama to trash the Constitution and make law never passed by Congress? Where in the Constitution does it state that the government can force us to purchase insurance? The list goes on and on.

All power is now being drawn to Washington. Worse, all power is being drawn to one branch of government—the executive. It is a replay of King John and King James trashing the Magna Carta and taking all power to themselves. President Obama and progressives in general (Republicans and Democrats) are attempting a federal takeover on an unprecedented scale by neutering state sovereignty, Congress and the Constitution.

When English kings John and James rejected the Magna Carta and Parliament, civil war resulted. Is that where America is headed? Will Americans continue to watch their sports or play their electronic games—oblivious to what this president and his supporters are doing to make Congress and our Constitution redundant?

Why do we continue to support politicians who defend the criminal activities of big government? It doesn’t matter if a politician is illegally doing something you may want. The illegal action establishes precedent and weakens everyone’s civil rights. It is time to recall, impeach or even charge with treason those politicians and judges who make a mockery of the rule of law that provides the liberty that was purchased by blood of our forefathers and Englishmen before them.

Dr. Coffman was president of Environmental Perspectives Incorporated (epi-us.com) and CEO of Sovereignty International in Bangor, Maine (sovereignty.net). He had over 40 years of university teaching, research and consulting experience in forestry and environmental sciences. His newest book is an updated version of “Radical Islam in the House” and is getting rave reviews.

See the print version of Dr. Coffman’s “Magna Carta” on rangedex.com by clicking HERE

You may also like

-

Arizona rancher sues to stop million-acre national monument

-

VDH: How to Destroy the American Legal System

-

Colorado conservation group sues wildlife officials for skirting NEPA to get wolves into the state

-

Polis adds another radical activist to Colorado Parks & Wildlife Commission

-

Public Land Expansion Syndrome in the West

“It is time to recall, impeach or even charge with treason those politicians and judges who make a mockery of the rule of law that provides the liberty that was purchased by blood of our forefathers”.

Great article!!

Thank you