The 2020 sheep shearing season turned out to be quite an adventure – more for some than others.

Background

Although I come from a sheep ranching family, and have been quite active in the sheep industry myself for the past 10 years or so, it wasn’t until just the past year that I really immersed myself in some of the most critical big picture issues facing the Western sheep industry, including crucial labor issues, including the serious shearer shortage, as well as the impending Western sheep operation succession/perpetuation crisis — and the corresponding opportunities.

Pinch Points in Western Sheep Production

Sheep ranching is a labor-intensive enterprise. It always has been. It requires a lot of manual labor. There are several major pinch points in the production cycle but one of the biggest is shearing. Most sheep have to be sheared at least once a year, and if wool ewes aren’t shorn before they begin to lamb, it can be a disaster.

One of the single biggest challenges for the western sheep industry in general, and especially the shearing business, is access to competent labor. “Finding mainstream Americans who are willing to herd, let alone shear, sheep is virtually impossible,” says one sheep shearing contractor.

Hard Work

To call shearing sheep “hard work” is an understatement. The actual work of shearing and removing wool from sheep is one of the most taxing and physically demanding occupations in the world – even if you’re in superb physical condition, and know what you’re doing. Running the clippers is the easy part. Once they learn the skill, shearers should be capable of shearing at least 100 head a day. Many can shear 150 head a day, and really good shearers can shear 200+ a day. Wrestling and manhandling big stout, uncooperative range ewes, and bending over for hours on end can really take the starch out of you. And shearing bigger, stronger rams is even harder. But learning to get the sheep to relax is one of the keys. Guys who really know what they’re doing can make it look easy. Still, the energy required for the work consumes over 6000 calories a day, and gallons of water.

Finding Help

There are not very many average Americans, including a lot of good healthy young guys, who are willing to even consider working this hard. According to that same shearing contractor, “We’re just too spoiled in this country. And not just this country, but in all these developed countries.” Consequently, to make it all work, most western shearing contractors have no choice but to depend on experienced and competent foreign shearing crews, primarily from South America, operating under H2A seasonal labor visas, under which the shearers work as independent contractors.

What’s at Stake

In terms of the big picture and American sheep industry demographics, it has been said that while 80% of sheep producers may live east of the Mississippi, 80% of the sheep in this country are produced west of the Mississippi, with many produced on fewer and increasingly scattered ranches in the West — generally far removed from East and West Coast urban centers where 90+% of lambs are consumed, almost entirely by urban ethnic populations, with a high percentage of that consumption coinciding with their religious holidays. The vast majority of the millions of pounds of lamb required to meet overall consumer demand for lamb meat in this country and beyond are produced in the form of 100+ lb Rambouillet/Columbia/Suffolk crossbred wool lambs produced in the West each year. I am speaking in generalities of course, recognizing that there are exceptions to every rule.

In terms of basic production model, a large percentage of these sheep move with the seasons, as part of Western open range sheep operations. They harvest the best forage on high mountain pastures in the summer, and winter on remote deserts, often putting marginal land and resources to productive beneficial use – land and resources that would otherwise have little productive beneficial use. They are produced under the watchful eye of full-time shepherds (referred to as “sheepherders” in the West) who live with the sheep 24/7.

Recent years have really tested the mettle of the short-handed labor and sheep-shearing infrastructure of the Intermountain West, where about 25% of total U.S. sheep numbers are produced, and sheared by a smaller and smaller handful of large-scale mobile shearing contractors, who operate in a limited amount of time to get all the sheep shorn before they start to lamb. With several Intermountain shearing contractors having recently gone out of business, and several others talking about going that direction, a general consensus has developed that the already acute shearer shortage is apparently only going to get worse.

Although there may be isolated exceptions to the rule, at this point, the Western sheep industry as a whole is completely dependent upon foreign labor from undeveloped countries, both for herding and for shearing. . . . because sheep have to be tended, and the wool has to be removed at least once a year, ideally before ewes begin to lamb. And if we run out of labor, the whole industry will essentially be out of business.

Objectives

As a result of all these realizations, I began to recognize the genuine need that exists, and started doing some serious due diligence in the latter half of 2019. Among other things, I visited with a number of sheep ranchers, sheep shearing contractors, and wool buyer, Will Griggs, who is in a unique position to seemingly bridge essentially all sectors of the sheep industry in the Intermountain West. One of the things Griggs brought to my attention was the serious state of Western sheep operation perpetuation, especially in some areas, where, among some seriously aging multi-generational sheep operators, there do not appear to be any family members in the younger generation(s) demonstrating any interest in taking over and perpetuating the operations. In light of the fact that I was already working with Stockman Grass Farmer (SGF) publication on the impending agricultural succession/perpetuation dilemma, I found this very interesting.

In the Fall of 2019, I also spent some time working with Fairchild Shearing, from Buhl, Idaho, on their Fall shearing rounds, and had a chance to visit with a number of Idaho sheep ranchers, and witness first-hand what Griggs had been talking about. Based on my experience working with Fairchilds, I did come away hopeful that, despite the lateness in the season, it might still be possible to jump through all the H2A hoops, and assemble a crew of Uruguayan shearers for 2020. So I began getting ducks in a row and started working on trying to navigate the H2A minefield.

For shearing contractors, however, there are several serious challenges, inherent conflicts, and which-comes-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg scenarios in the H2A process. The first is that you have to have signed work agreements with all the sheep ranchers before you can even attempt to bring in a shearing crew. But what sheep rancher in his/her right might would sign a work agreement unless/until they knew you could in fact get a crew and be able to shear? And what responsible shearing contractor would want to have sheep ranchers commit, and depend on them to get the job done if they didn’t even know yet whether or not they would be able to get a crew? It’s a genuine Catch-22. So, when things didn’t start falling together within a reasonable time frame to instill confidence that I could get the H2A process to work in 2020, I started looking other directions.

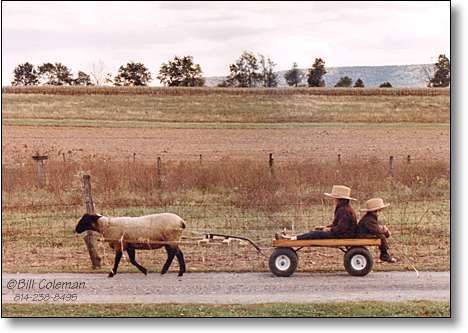

The Amish Direction

As I started exploring other directions that would not be as hampered by the time constraints, expense, and stifling over-regulation of the H2A visa program, I wondered where a person might look in this country to find a population of production-oriented people, with a genuine interest in agriculture, real work ethic, and a demonstrated interest in manual labor? Among other things, I relied on several decades of personal experience and background, to point me toward the Amish.

One of the first things I wanted to figure out was if there were any areas in the United States where the Amish might have started to seriously embrace sheep production. I figured that if there were such places, sheep industry support infrastructure, including shearing, etc., would have to evolve to meet the corresponding need(s). My due diligence led me to Eastern Ohio, and a group of retired Ag extension agents, including Daryl Clark and Don Brown, who had essentially spent their careers working as liaisons to the Amish community.

With the help of many people, and after making multiple trips to Ohio Amish country, running ads in horse & buggy oriented papers, including both The Budget and the Busy Beaver of Ohio, ultimately I was able to recruit a group of adventurous souls who were willing to come West and try their hand at both shearing and wool handling for the 2020 shearing season. I do want to note, however, that despite all the advertising, etc., phone calls, and personal visits to Amish families in Ohio, if I had not physically been at the monthly Mt. Hope horse sale in January, and had not asserted myself to approach and strike-up a conversation with a group of young Amish men talking around a fire in a barrel, I would not have made the contacts that eventually and ultimately led to the relationships that resulted in the core group of the shearing crew we put together, most of whom were related and/or worked together on the same concrete crew. Amazingly, within just over a month from that first contact, and with any serious concerns about the Corona Virus outbreak still months away, they were headed West to shear sheep . Out of respect for the privacy of the good souls who took the leap of faith to come West and give it all a try, in terms of summarizing that whole experience, I am going to speak primarily in generalities, without identifying them by name.

In preparation for that adventure, I sponsored a one-day sheep shearing class in Holmes County, to give some of the shearing recruits an opportunity to get their feet wet under the able instruction of Travis Johnson, a very promising young sheep farmer/ shearer, who had sheared in Australia last fall, and did a great job instructing the class.

Our Work

Because I was not able to recruit quite as many Amish shearers as I had hoped, with the help of Lars Woolsey, I ended up farming-out the primary group of shearers to Marty Stubbs, a beginning shearing contractor, who was looking for a crew, while I agreed to spend most of the shearing season managing a larger Peruvian shearing crew, supported by an Amish family who agreed to work with me, handling the wool and operating the wool press for the Peruvian shearing crew.

In the entire group of Amish shearers, there was only one who had any experience shearing sheep prior to attending our sheep shearing class, and his experience stood him in good stead and he was able to really hit the ground running. Predictably, the other shearers got a little slower start. Shearing sheep is really hard work.

Once they realized just how hard it really was, the first day or two they seriously considered and discussed the possibility of just quitting and heading home. But there is an old saying “when the going gets tough, the tough get going.” Obviously, a “legging up” period, to have a chance to kind of get in shape is important. And the elevation can really make a difference. When suddenly going from less than 1000’ elevation in Ohio, to 5000+’ in the mountain valleys of Southern Utah, without a reasonable opportunity for acclimation, it can be much harder to breathe, especially when engaging in strenuous physical exertion.

All our Amish friends experienced the effects of the higher elevation. But that was one of the most critical differences between these Amish shearers and normal mainstream Americans, most of whom would have thrown in the towel the first day, probably before noon: when the going got tough, these guys didn’t quit. They hung in there and stuck it out, in some cases going from zero to 120+ sheep/day in just a month’s time – which is quite a feat. Through their diligence and perseverance, they picked it up amazingly well, and learned to shear remarkably clean – much to the appreciation of the sheep ranchers they sheared for.

In addition to shearing, we also had Amish wool handlers for both crews. For the Amish shearing crew, one of their wives did a great job processing the fleeces and running the wool press. For the Peruvian crew I had a whole Amish family, including husband, wife and four children, helping handle the wool. The husband became a very capable and proficient wool press operator. Right at first, with the elevation change, etc., he too seriously wondered if he was up to the task, and may have seriously considered quitting, but he didn’t. Instead, he picked up the pace, stepped up to the plate, and learned how to hustle, and how to turn out a very impressive wool bale.

Although his wife had her hands full wrangling their four young children, and at times cooking for the whole crew, she also really eased our work load when she helped carry fleeces. We really appreciated and missed her when she was otherwise pre-occupied.

A lot of people have questioned my sanity for taking on the responsibility of a whole family, including four young children, on the shearing trail. For almost two months I was with them almost 24/7, as we moved around shearing for dozens of sheep ranchers in Utah and Colorado. Among all the other blessings I derived from that whole experience, though, one of the greatest was the opportunity it to observe, very up close and personal, over a significant period of time, and under some very challenging circumstances, genuine marital teamwork, and probably the best parenting skills I have ever seen in my entire life.

Kids will be kids. And although we pushed these kids to the very limit, their parents took it all in stride, and nurtured their young family through it all with dignity and grace. In the process, I was treated to a truly advanced course in marital harmony, parenting and nurturing. For that reason, alone, despite the challenges, it was a true delight.

Insights

I found my work with the Amish to be genuinely refreshing, and uplifting. One of the most impressive things about the Amish folks I worked with was their steadfast production orientation.

In contrast to mainstream American society which has become almost completely consumption oriented, it was truly impressive and a big breath of fresh air to work with people who were more interested in and concerned about what they could produce rather than what they could consume. And the women I worked with were just as production-oriented as the men, and may have carried a disproportionately heavier share of the load in terms of making things happen. As one of them told me, there is an old Amish saying to the effect that, “A man’s work is from sun to sun, but a woman’s work is never done.”

The husband and wife I worked with were the epitome of marital unity and teamwork. Rarely in my life have I witnessed a couple who were more devoted to their relationship and their family. Despite everything the young Amish wife/mother had on her plate, from wrangling kids, to handling wool, and cooking for her family as well as the crew at times, she was never heard to murmur or complain. It has been said that the more secure a person is at the core, the more insecurity they can handle at the edges. During a time of multiple challenges, including everything from long cross country travel to continual upheaval and great temporal insecurity, both because of our continual travel, the circumstances of our work, and the Corona Virus Outbreak, this husband/wife team were the epitome of inner security.

Moreover, across the board, all the Amish men and women I worked with were very straight-up, straight-forward, and remarkably willing, eager to please, and positive in their attitudes and outlook. In my dealings with them, there was a total absence of all the games, manipulation and drama that often accompany dealings with mainstream Americans. Consequently, compared to dealing with “English” (mainstream Americans), dealing with them was like a breath of fresh air. Their open, honest communications, positive attitudes, and steady reliability were truly impressive. They were a genuine credit to their families, communities, and upbringings.

But the reality is, the whole venture did end sooner than I had planned. Although they slogged through the height of the Corona Virus Outbreak, as time passed, and restrictions became more stringent, including in their home state of Ohio, they became more and more concerned about their ability to travel and get home, and rejoin their families and communities, which is their tried and tested safe haven. Consequently, earlier than anticipated, I ended up loading them on a train bound for home.

With my shearing season cut short by their early departure, for perhaps the first time in my life I experienced true depression after they left, and I had to return to the realities of dealing mostly with high-drama, consumption-oriented “English” folks. I will have to say that it was a big let-down, and I experienced genuine depression as I transitioned back to my otherwise very fortunate and highly enviable life on the ranch – especially in late April and early May when our place along the banks of Corn Creek, outside of Kanosh, Utah, is about as good as it gets. In my view, there were two primary reasons for the big let-down.

The first reason was simply crash-landing back to the realities associated with the inevitable general difference of attitude and life approach between the Amish and mainstream Americans. Another even bigger reason was recognition of the vast difference between the concept of “community” as the Amish experience it, versus how we, as mainstream Americans, do.

What I have learned from my experience is that unlike most mainstream American communities, Amish communities have a much stronger foundation in basic shared values. As opposed, for example, to the otherwise seemingly idealistic little rural community where I live — which has evolved to the point that despite its rural location, at this point the vast majority of residents now probably lean more towards consumption-orientation and more urban values — members of

Amish communities are virtually all production-oriented, with strong rural/agricultural values, and a much stronger sense of unity and shared Christian purpose.

Ever since I became fascinated with the Amish decades ago, I have known and developed some understanding of their ultra-strong sense of community, and corresponding social support network. During this undertaking, however, including both in my multiple travels to Ohio, as well the prime opportunity I had while we worked and lived together, to both observe, hear about, and experience some of the realities of their keen sense of family and community, the importance of all that became much clearer to me. In my final conversations with my Amish friends before they headed home, we had the opportunity to discuss some of this, and talk about why any long-term experience for them in the West would have to address their vital need to be part of a like-minded community – which means that any vision for a long-term experience and/or relationship would need to acknowledge and thoroughly address that reality.

Recognition, Credit & Gratitude

As mentioned previously, although there were many people, too numerous to mention, who aided and helped this whole undertaking along the way, I do want to recognize and express gratitude to some specific people who made major contributions to the whole endeavor. First of all, a sincere thanks to the good, hearty Amish souls (who will continue to remain nameless here), including men, women and children, who ventured West to shear sheep, handle wool, and get a taste of the Western sheep industry. They are modern pioneers, and true credits to their families, communities, and upbringings.

I also want to thank Lars & Merin Woolsey, without whom the whole operation could not have happened. And thanks to a number of folks in Ohio, including Don Brown, Daryl Clark, Willis & Cathy Miller, Travis Johnson, Duane Raber, and David & Tonya Campbell, for their significant contributions in my travels and recruiting efforts.

Stan & Bev Kelsch Family and Dan & Janna Neville deserve thanks for rolling out the red carpet for our Amish friends here in Utah to help provide initial temporary accommodations, fellowship, support, and longer-term accommodations. And big thanks to Caleb Hatton for an inconvenient, late-night rescue and other back-up support.

Ultimately, however, the whole experiment/undertaking would not have worked the way it did if Marty Stubbs had not been fully committed to shear about 10,000 sheep, but didn’t have a crew, and was in serious need of a shearing crew to get it done. So serious thanks to Marty for sharing in the whole adventure and providing opportunities for our Amish friends to work, learn, and develop fundamental skills. And sincere thanks to the whole Scott Stubbs family for allowing their entire sheep herd to be used as guinea pigs in the learning process. I also want to acknowledge and thank Craig & Scott Jones, Tony Gonzales, and their families for letting us share their farm while we were working in Iron County, and my sister JoAnn Wickel for hosting our stay while we were working in Sanpete County. Finally, I also want to thank all the good people along the way, including a long list of sheep ranchers and their families, employees and helpers, who provided encouragement, support, and many top notch meals as we worked with them to get their sheep sheared and wool handled this year. I hope to continue to foster all of those relationships.

Final Food for Thought

As alluded to in my accompanying May 2020 SGF article, on one hand, I genuinely believe that the current realities of the Western sheep/wool industry and the realities of Amish culture and society present a golden opportunity for a potential win/win match-up between the two. On the other hand, although it is clear that the Amish will continue to survive and thrive (and have done so for centuries) without the Western Sheep Industry, at this point, even at this time of need, as the Western sheep industry is postured for and anxiously awaiting government financial assistance, regardless of short-term Band-aids, recognizing that for at least the foreseeable future it is going to continue to still require all available labor resources, including Peruvians, Mexicans, and Uruguayans, to keep the Western sheep industry going, I am not entirely convinced that the Western sheep/wool industries, which are genuinely experiencing some real challenges right now, will ultimately be able to survive without the Amish, and a healthy injection of Amish labor, innovation, capital investment, and frugality.

Even after receipt of any sort of government assistance that may occur, there will still be a great need for sheepherders, sheep shearers, wool handlers, lambers, hunters/trappers (to help control predators), and perhaps even most importantly, the greatest need will be for fresh new blood, new vision, and prospects for new generations and families of dedicated, production-oriented sheep ranchers, with a deep and abiding love for agriculture, who are capable of not only navigating the current minefield, but also capable of helping to take the Western sheep/wool industry into the future. Given current industry demographics, there is a genuine need for fresh, young blood and ownership in the industry. From my perspective, the generally low-tech, sustainable, centuries-old basic production model of the Western sheep industry would appear to be a natural fit for the Amish. Unfortunately, up to this point, the two have not yet had much introduction and/or opportunity to become well acquainted. But hopefully that can change, and the opportunities that exist can be thoroughly explored, including wide-open areas in the West that still offer plenty of room for expansion and growth.

You may also like

-

Protect The Harvest: The whole truth about Western ranching

-

Hero guardian dog that killed 8 coyotes nominated for Farm Dog of the Year award

-

Nevada tries illegal means to force sheep rancher of his lands

-

Bighorn sheep are the next weapon in anti-grazing zealots’ arsenal

-

“Net Zero” and the American beef industry cannot co-exist

Wonderful article fills my soul. I grew up in rural Iowa that was an intact community and life revolved around the church, school, and the farm. My family settled there in the late 1800’s as land became available and moved from Illinois on the train and purchased land from the railroads. My Aunt who passed years ago remembered when there were no roads across the Tall Grass Prairies. As hybrid corn arrived and the consolidation of agriculture, mechanization where you could grow thousands of acres the farm communities contracted and people like myself found opportunities beyond a town of two thousand that once was isolated. Everyone worked hard and my memories are of the huge gardens and the work of planting but canning and food preservation and meals that had plates of meat of every kind pork, chicken. beef and wild game. The town I knew is now a food desert and the consumption of fast and processed food. Centralized control has destroyed quality and nutrient value of food along with the destruction of a community and its values that were held by the majority. The Amish we need to celebrate for continuity and values and a positive sign that will save the sheep industry.