Special Report: Cowboys or buffalo?

As published in the RANGE magazine Fall 2019 Edition

Critical Mass

The most ambitious and successful “rewilding” effort ever attempted faces stiffening opposition from Montana’s producer communities. Who will win? Well, it’s complicated…

Words and photos by Dave Skinner.

In 2012, RANGE published “Buffaloed,” covering attempts by both Indian tribes and a private nonprofit to acquire bison for eventual release as wild herds, freed to roam across millions of depopulated high-plains acres in Montana.

Seven years later, and over 30 years since Rutgers urban-studies academics Frank and Deborah Popper publicly sprang their “Buffalo Commons” proposal, where do matters stand? Will thousands of buffalo, which Congress recently designated America’s “national mammal,” soon thunder horizon to horizon across a new 3.5-million-acre “reserve”? Or more? Or not?

Critical Mass

In essence, this story is about “critical mass.” The Manhattan Project was basically a race to collect enough atoms to make a bomb and end World War Two. Without critical mass, all the work would be wasted. With it, total victory—well, at least for a while.

Here, across a giant, lumpy chunk of central and northeast Montana straddling the Breaks reach of the upper Missouri River, the American Prairie Foundation is trying to gather together a critical mass of land, money and buffalo.

Created in 2001 by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) as a “land trust partner,” American Prairie Foundation (dba Reserve, or APR) set a goal of raising $450 million over time, buying a half-million acres of private “base” properties associated with millions of acres of grazing rights on multiple-use Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, as well as some grandfathered grazing rights on the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge controlled by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), then combine the whole mess into a unified “reserve” of 3.5 million acres, as the American Prairie Reserve. On that reserve, as APR board member Susan Myers says in a promotional video, “someday we want to see a herd of 10,000 bison in our lifetimes.”

Will she? In the media, APR is already claiming victory, with an admiring Great Falls newspaper reporter relaying without comment APR’s narrative that its holdings, magically “[c]ombined with 1.1 million acres of CMR lands, the roughly 1.5 million acres assembled to date represents the largest area devoted to wildlife conservation in the Great Plains.”

However, as will be told here, that rosy foregone conclusion may be mistaken, for it seems another critical mass, this time in opposition to the reserve, is developing and growing.

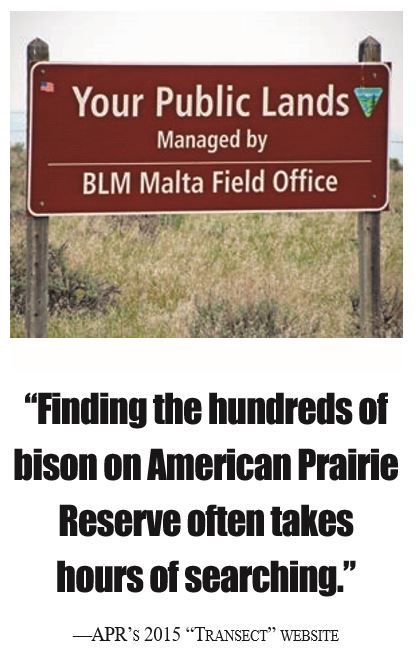

Bouncing down into the Judith River canyon, RANGE chauffeur and retired military officer Ron Poertner of Winifred snorts: “Who the heck do they think they are? What automatically entitles them to run buffalo in the monument and CMR? That’s still public land!”

The Capitalist Road

Besides audacity, the reserve is noteworthy for not being Green business as usual. Ever since Earth Day 1970 and the passage of environmental laws Congress passed in response, environmental groups have almost completely focused on using those laws to attack every sector of America’s economy, politically and in the courts. Forestry in the Northwest and the decline of coal are both examples of how the law has been worked.

However, and not surprisingly given the good philosophical fit of Marxist theory to Green command and control (i.e., Green New Deal), one attack strategy rarely considered, much less attempted, and only once successful, is the “capitalist road,” i.e., outbidding your rivals for the resource.

Well, one big capitalist did just that. In 1927, encouraged by his pal, Yellowstone Park’s superintendent, oil baron John D. Rockefeller Jr., set up a false-front entity in Wyoming’s Jackson Hole Valley—the Snake River Land Company. His idea was to secretly buy up working ranches, not to make a big ranch, but to turn all of it over to the Park Service to add to Grand Teton National Park. Word got out in 1930, to wide outrage, and Rockefeller’s scheme stalled. In 1943, after Rockefeller threatened to sell out, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes convinced Franklin Roosevelt to create a national monument (shades of Bruce Babbitt and Bill Clinton). In 1950, Rockefeller’s wish came true, while Wyoming wrangled exemption from the Antiquities Act. Granted, the land ended up a gift, but the Rockefellers could afford it, and gifts are deductible.

Today, instead of hoodwinking judges or buying politicians, American Prairie Reserve flies a flag of “free market principles,” handing over bags of cash provided by a shockingly small gaggle of Forbes 400 billionaires to pay for, and get, what it wants. Trouble is, nobody except perhaps APR’s donors knows precisely what that will be.

However, it is safe to say that APR intends to permanently eliminate production agriculture from a large landscape, in favor of “restoring” the full suite of native flora and fauna, including predators. APR public communications mention only a “reserve,” never overtly discussing whether the final product will be a privately supported reserve open to the public, donated to become a national park as with Rockefeller, or sold to the government at “free market” value to, yep, be a park.

In Grass Range, Mont., LeAnne Delaney notes: “We ranchers invest, too. APR’s backers are going to want some return on their investment, I just don’t know what. I think they will try to flip it to the federal government, take the cash, and target someplace else to save. We should know that before APR goes any further.”

Besides money, what about on the ground? State representative Dan Bartel (R-Lewistown) asks a question on many minds: “Let’s say APR gets 10,000 bison out there. What happens if the fences break? If the range is overgrazed? If the money dries up and the whole scheme fails? What happens with 10,000 buffalo? If APR falls apart, who will be responsible? The state of Montana? The counties? The feds?”

Whatever results from these “free-market” methods matters, because both success and failure will set a precedent, just like Rockefeller did in Jackson Hole. If the investors get a return, they may “reinvest” elsewhere in America. If APR falls apart, that’s another precedent.

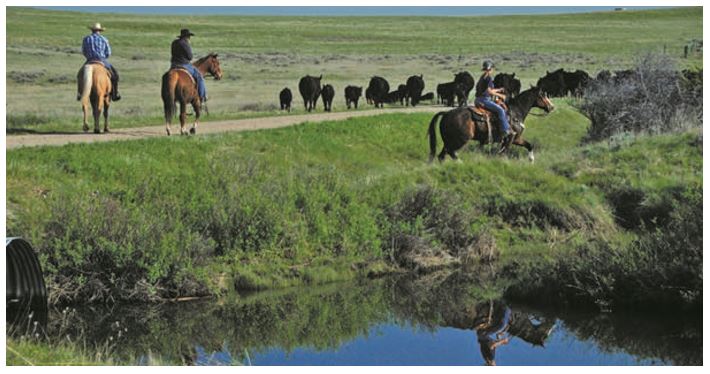

plus Ben, Vicki and Dustin Hofeldt.

Pulling the First Brick

In Lewistown, RANGE was welcomed into the offices of the Fergus County commissioners for a quick chat and to pick up copies of a bison-related ordinance the commissioners approved in 2016, plus other documentary gems.

As a whole, the commissioners are worried about a reserve, although the city government is on board. Commissioner Carl Seilstad, a Roy-area rancher, has long been involved with diversifying and growing the region’s economic base, but doesn’t view APR as a growth positive: “Whenever APR buys one of these ranches, the cattle come off, they don’t buy equipment. Businesses and government are both losing revenue.” Commissioner Ross Butcher adds, “As soon as you pull the first brick out, the whole house starts coming down.”

But which house is coming down? Butcher isn’t sure, but in the summer of 2018, APR bought the 13,000-square-foot Power Building in Lewistown, to serve as a “multimillion” National Discovery Center. Again, our friendly Great Falls reporter was happy to pass on APR’s claim that the center “will be on par with national park-run facilities.” National park, hmmm?

While “fund-raising is underway,” for now, the Power Building sits vacant. APR’s existing, dirty-windowed “center” sits mostly unstaffed and dark on Lewistown’s busiest corner. Based on what he sees every day downtown, and what he hears and reads in his office, to Butcher: “Obviously, economically APR is not viable. It can’t be a long-term self-sustaining operation.” Is he right?

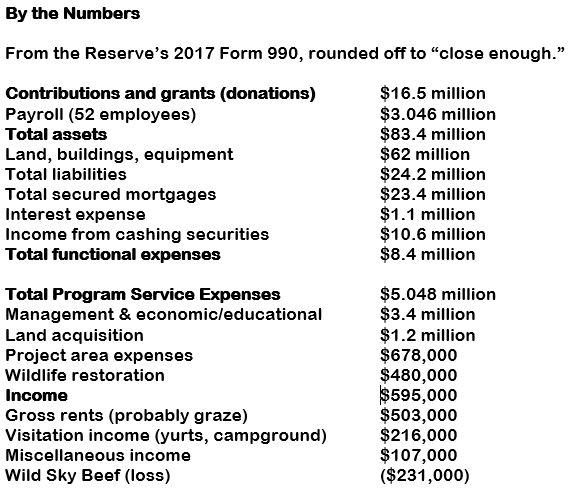

American Prairie Solyndra?

Only APR’s accountants know the full truth of American Prairie Reserve’s fiscal health, but as a nonprofit, APR must file tax returns that are mostly public record. Importantly, donor identification is kept safely hidden from prying peasants, especially journalists who can run a calculator and use Google.

But before we pry, some background. The late 1990s were a great time to be Green, with the Clinton administration in full mutual support. At the same time, the information revolution enabled the use of “big data” across “big landscapes,” especially data collected through “natural heritage” programs and organized with Geographic Information Systems. Large environmental groups like The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund harnessed this river of information to identify high-value habitats and then, of course, prioritize them in terms of “return” for conservation “investment.” In a nutshell, anything was possible, and Al Gore was gonna be president next!

One region full of conservation promise was, um, the Northern Great Plains ecoregion, what normal people call the shortgrass prairies from western Nebraska up to southern Alberta. Most promising?

Well, in 2000, The Nature Conservancy threw down first, buying the 40,000-acre Matador Ranch some 20 miles southwest of Malta from its stressed owners. Just a year later, WWF propped up American Prairie as its partner and agent. Remember the $450-million, half-million, three-point-five numbers? That was supposed to be a sideshow to the real plan! An epic 191-page think paper funded by WWF in 2004, “Ocean of Grass,” aspires to much, much more. From 178 million acres, half of two provinces and five states, “27 million acres… including two or more areas of several million acres each” would be carved out for “restoration” by 2020. A bit optimistic?

By themselves, American Prairie Reserve’s numbers look impressive. But in terms of meeting goals over time and getting to critical mass on budget, the numbers are awful. APR currently claims “28 transactions” completed, giving it control of about 94,500 acres of private ground and 311,000 acres of grazing lease rights. But those acres came at a high price. Ranch land goes for six times what it did prior to APR’s creation, and not all of that is the Bush-era “boom-bubble” or rich trophy-ranch buyers. For-profit ranchers are cut out of the market, unable to invest in the landscape they’ve lived in for generations.

APR also brags to the world its ranch buys enabled retirement of 63,777 acres of grandfathered “cattle grazing leases in the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge,” meaning the feds can “now restore the habitat primarily for wildlife use.” So, even if every acre “counts,” APR is still crawling an 80-year path to the finish.

What about the thundering herd of thousands of bison? In 2012, there were 286 buffs on 12 “transactions” totaling 121,000 acres (38,000 base). Today, there are about 800 bison on “American Prairie Reserve’s 32,000-acre parcel in the middle of the reserve,” eating base plus two allotments (converted 1-1 cow to bison in 2012) 40 miles of ruts from the nearest pavement any way one cares to get there. Sorry, but 800 is just eight percent of 10,000, a goal that looks at least a “lifetime” away.

Devilish Details

There are multiple websites that post “nonprofit” tax returns for public study: Guidestar, ProPublica, and the Foundation Center are examples. Guidestar provides three years of Form 990 returns for registered free users. Paid users can go much further back. But in all cases, keep in mind that there is a huge delay between the actual fiscal year and when new returns finally become public. APR’s latest available Form 990 covers FY 2017, ending December 31. It was posted on Guidestar in early 2019, a 14-month wait. (See “By the Numbers” on page 19.)

So, what about those numbers? The $62 million in assets are “land, buildings and equipment,” an $8 million over-year increase that closely matches the publicized asking price of the Two Crow ranch APR purchased in 2017. APR puts some “project area” and “restoration” money on the ground. But fund-raising costs way more: $2.32 million total, with $900,000 going in “other” fees for services, against $888,000 in-house salary ($258,000 to executives), benefits, and payroll tax.

The most striking part of APR’s numbers is the utter lack of income. Taking away donations leaves only $826,000 against $8.4 million in overhead. That’s the kind of numbers Silicon Valley start-ups post just before total meltdown, right?

Might APR be putting aside an operations endowment to sustain what looks like a permanent loser? Nope, even though in a 2013 interview, then-APR-board-member Audrey Rust was totally transparent with what she thought would only be read by a small, friendly audience, that of the far-left Lincoln Institute for Land Policy (LILP). She warned “plans are incomplete for the permanent private protection of [the reserve, and] raising the necessary endowment funds…has been slow.”

Rust was being nice. APR’s “endowment fund” for future needs, including operations, is microscopic. Its 2012 balance was $854,000, in 2017 $1.27 million, with all the balance growth from capital gains, not new contributions. And only 30 percent of that is permanent endowment. So it’s no wonder Rust also saw fit to remark, “APR staff and leadership are under great stress to meet their financial obligations.” Then, and certainly now.

Germans Love the West

Then there’s a line item called “transactions with related organizations,” usually buried in the page 40s of a typical return: Friends of the American Serengeti in Frankfurt, Germany, founded in 2011.

APR currently holds two of the seven positions on Friends’ board of directors. Those two seats are almost certainly held by APR board members Liliane and Helga Haub, members of a family which controls an international, multibillion-dollar retail empire, the Tengelmann Group, with family members in both America and Germany, some holding dual citizenship.

RANGE has tax returns for 2014 through 2017, showing the Germans contributed $102,279 in 2014, nothing in 2015, $1.087 million in 2016, and $995,291 in 2017. The final two years are close enough to an even million to consider the exchange rate made the difference. Germans can donate up to 20 percent of their pretax income, and in Germany the tax rate on incomes over 265,000 Euros ($299,420 U.S.) is a whacking 45 percent. So whoever donated those two million-dollar gifts got a $450,000 write-off. Very nice—or in German, sehr nett!

But Lewistown’s Anna Morris, a Montana farm girl turned ag-equipment sales representative, doesn’t think that’s nice at all. “It’s not average Americans we’re upset with. Not only are American billionaires attacking our American dreams, but foreign billionaires too?”

Dancing on the Head of a Pin

First, to be considered a public charity, and not just a zillionaire’s pet project, 501(c)(3) organizations are expected to get at least two-thirds of their funding from the “public” or the government. Public is loosely defined as a person (or “entity”) that forks over no more than two percent of total funding over a five-year period. For APR, that threshold, set over a five-year cycle, is $963,906, $193,000 yearly. That’s a darn rarefied public—and this tiny public of six-figure donors paid in fully $27.5 million, or 57 percent, of APR’s total income of $48.2 million.

APR staff has been aware of this for a long time. Audrey Rust stated to LILC that APR probably has “singular appeal to extremely wealthy individuals who, like the Rockefellers [Yep! Them!] decades ago, could create this reserve with their philanthropy alone.”

APR’s dependence on big donors has bounced it back and forth over the 33.3 percent “public charity” line, dropping to 28 percent public funding recently. When, in 2015-16, APR dropped below the automatic public charity line, but above the 10 percent line that automatically defines a private foundation, APR had to present “facts and circumstances” reports in order to keep public charity status (and the tax goodies). Both are illustrative. From 2016: “Since its inception in 2001, APR has received contributions from 2,592 people/entities.” There are 300 million Americans who have not contributed, and probably never will.

And, “Only five of our [2016] contributors qualified as major contributors in 2015.” Sure they did, but those five forked over scads of money.

But APR needs more. As Rust told the LILC, it faces “a pipeline problem” of a narrow donor base, “status is not associated with being a supporter [Ouch!],” and APR’s lofty $450 million goal “would need to attract a gift of $80 to $100 million at the top of the fund-raising pyramid.”

Fergus County commissioner and businessman Ross Butcher observes, “The large investors seem to have some sort of tax scheme figured out, where they’re making more off donations and write-offs up front.”

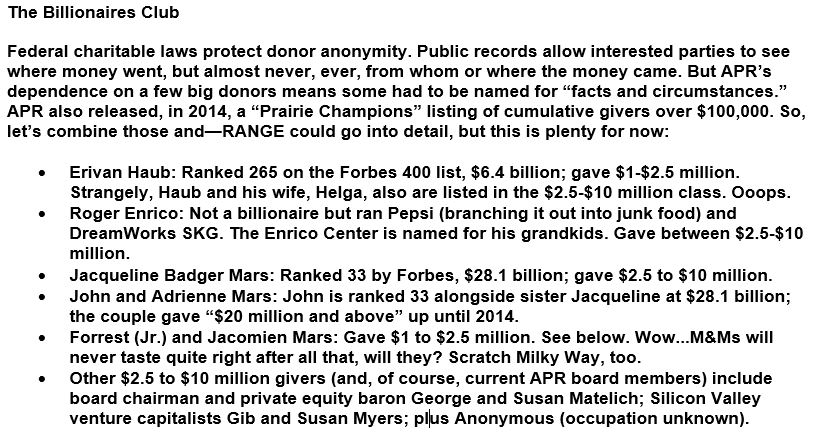

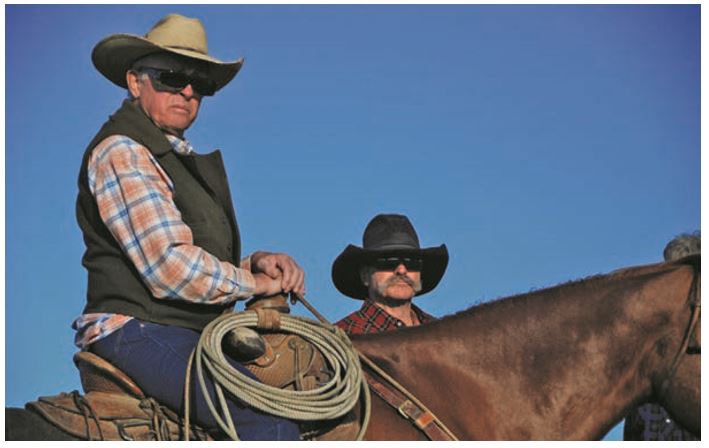

PHOTO CREDIT: ©Dave Skinner/RANGE

That Lifetime Thing

In short, just seven super-wealthy couples, three from just one tight-knit family, have carried American Prairie Reserve since the beginning. APR reveals another 13 people and entities, including the late Paul Allen (Microsoft), giving over a million each. But the beginning, as Winston Churchill explained, may be ending—the pipeline rusting out.

First, Roger Enrico died in 2016 at age 71, snorkeling at his Cayman Islands’ home.

Also gone, glowingly eulogized by APR president Sean Gerrity for not only the “series of financial gifts which helped us to acquire a great deal of new land and initiate many other big ideas, [but also] carefully tending the Uncle Ben’s rice” Gerrity ate, is Forrest Mars. Ranked 25th on the Forbes list, with a $22.9 billion nest egg when he died in 2016, part of his fortune went to daughter Victoria Mars (currently Forbes 272, $7 billion).

Then, according to Forbes, “[Erivan] Haub was with his wife, Helga [an APR board member], at his buffalo ranch in Wyoming at the time of his death” in March 2018. Shockingly, Haub’s eldest son, Karl-Erivan, then the CEO of Tengelmann, disappeared the next month during a big mountaineering race in Zermatt, Switzerland. He is presumed dead.

Hmmm. It isn’t clear how dedicated the heirs will be, but more will be known soon enough. Jaqueline Mars is 79. John Mars is 83.

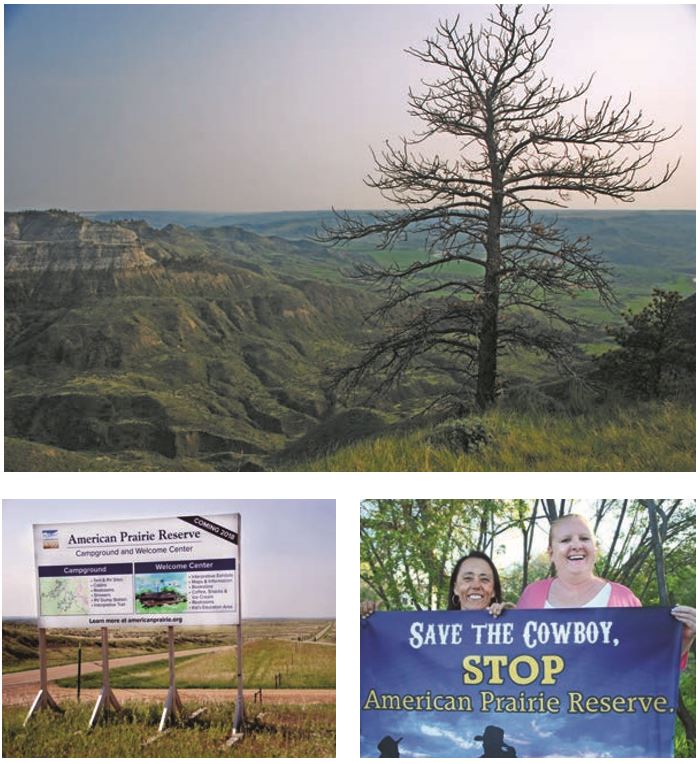

Where’s the Tourists?

Besides the scary things going on with American Prairie Reserve’s finances, there are indicators on the ground that APR’s core concept is fundamentally flawed. In order for its model to work, APR has to first spark imaginations, then keep the dream alive with tangible success, or “deliverables.” In other words, interest potential visitors (and donors), then blow their minds (and checkbooks open) upon arrival, again and again.

Built in 2013 with funding from Forrest Mars, and “open only to donors” until 2017, Kestrel Camp is a glamour camp—basically a five-star hotel set up in a cluster of seven yurts. Prospective customers can download a 20-page brochure (really!) but must contact APR directly for availability (donors have first call).

What does it cost? An otherwise-revealing 2016 Bloomberg Pursuits advance story reveals that two nights (minimum) are “$2,400 per person, including meals” with a Chez Panisse chef. For supper: “Sous vide rib-eye loin with golden yams in a horseradish crème and, for dessert, sponge cake with whipped ricotta, peaches, and edible marigolds and nasturtiums.”

Pursuit’s writer also mentions sampling a “transect,” a fully outfitted cross-country excursion “by foot and mountain bike” (and canoe), which explains APR’s “Transect” 2015 fund-raising loss noted above.

APR also offers Buffalo Camp, 50 dirt miles south of Malta, nearish to Enrico and Kestrel, 13 lucky sites at $10, or $15 with power. But realistically? Assuming all 2017 visitation ($216,000) was at the yurts for $1,200 a night, spread across the 180-day “May-October” season, that’s one per night, at best. Worse, Kestrel can handle eight to 10 visitors.

If everyone roughs it at Buffalo, that’s 21,600 total visitors, or $120 per night, not possible with 13 sites. Even if possible, not much of a “best case,” considering as Pursuits put it, APR is “working to put itself on the map with Yellowstone […Grand Teton…] and Glacier National Park.” Yellowstone alone gets four million visitors. Even on a 365-day season, that’s still 11,000 a day.

From his ranch two mountain ranges west of Kestrel Camp, Big Sandy Conservation District chairman Dana Darlington sees APR’s fundamental challenge clearly: “Competition. Ordinary Americans already have easy access to a good experience in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone, with buffalo, grizzlies and wolves right off the roadside.”

Yellowstone isn’t all. There’s a bison herd at Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota. In Montana, the Fort Belknap reservation proudly promotes its Snake Butte herd. Fort Peck is working on the same thing. The Blackfeet already display their tribal bison herd in pastures on both sides of U.S. 2 west of Browning, against the spectacular backdrop of, you guessed it, Glacier National Park.

By stark contrast, when it comes to APR’s 800 bison running 32,000 acres, a lonesome “Transect 2015” photo caption nails APR’s most-fundamental problem: “Finding the hundreds of bison on American Prairie Reserve often takes hours of searching.”

Has APR finally clued in to what everyone else knows, what every retailer understands as “location, location, location?” Seems so. Soon to open, a year late, is Mars Vista camp. Unlike all APR’s other excruciatingly remote locations, Vista sits right next to U.S. 191 at the tip-over down the hill to the Fred Robinson bridge across the Missouri, at a place famed as a hunting-season elk hidey-hole.

Plus, the same “location” motive might have driven the purchase of at least one of two major, attention-grabbing ranch buys APR made—PN and Two Crow.

Both are at least three dozen air miles distant from any other APR holdings, on the “wrong” south side of the Missouri, completely inappropriate in terms of “connecting” habitats for “function.” But, but, but—both Two Crow and especially the PN are scenic, with the acreage needed by a good-sized “show-off herd.” Best of all, the PN has nice roadside bottom pasture, closer to “civilization” along just one, “better” but still primitive secondary road—not 50 miles this-, that-, and what-away from what is already the back of nowhere.

Simply put, lacking a convenient “showcase” for its bison, APR can’t capture hearts, minds, and above all, dollars. Yet.

Where’s the Beef?

Partly to woo rightly skeptical producers and businesses, and also to capture forage value in the interim until buffalo take over, APR established Wild Sky Beef as a marketer of “green” niche beef products. Touted as “grass fed” and predator-friendly, with bonuses being paid for proof that preferred species inhabit Wild Sky partner land, apparently Wild Sky hopes to eventually “blur the boundaries of the reserve with surrounding agricultural lands.”

Trouble is, while Wild Sky lacks the 10-1 burn rate of APR, it’s still a skunk: Losses of $147,000 in 2015, $64,000 in 2016, and $231,000 (on sales of $2.6 million) in 2017—simply too small to have moved the market needle, fiscally support APR, or “blur” any boundaries.

Anna Morris points out the irony of a group trying to eliminate beef grazing while marketing Wild Sky Beef, then segues to another: “Everyone loves the romance of cowboys and the western landscape. The irony is, APR twists that romance, trying to eliminate real American cowboys and the heritage they represent from the very landscape people dream of when they think of the West!”

Where’s the Grass?

Another big red flag is flown by APR’s paltry “rents” income, which covers subleasing of BLM grazing lease rights attached to 18 allotments upon which bison are not yet allowed to graze. APR posted $503,000 of “gross rents” for 2017, which could cover grazing leases as well as base-property rentals. However, the number doesn’t seem to fit against other known data. In documents discussed further down, APR states for the record that it now controls 31,893 animal unit months on 18 Bureau of Land Management allotments, plus another 19,235 private-base AUMs and another 4,440 state lease AUMs, a total of 55,568 AUMs.

On that, APR plans to “stock” 4,360 “indigenous animals” year-round.

But, if APR was successfully renting out its BLM grass for cattle grazing at its current average asking price of $28.04, one would expect about $894,000 income all told.

If everything was rented at $28, that’s $1.43 million in expected income, leaving APR $900,000 a year short. Even factoring in the 800 bison eating 9,600 AUMs a year leaves 45,968 AUMs, worth $1.27 million at $28 a pop. But APR is only able to rent $503,000 worth. Why?

The Control Freaks

Dustin and Vicki Hofeldt were APR graze lessees when RANGE met them in 2012. They had bought a ranch in the Sun Prairie area and leased three years of grazing in the East Dry Fork allotment from APR, which had bought the Frye Ranch base property immediately to the north. East Dry Fork is three pastures totaling roughly 19,000 BLM acres, which in turn are all shared in common with the Jacobs Ranch to the south and east. While the Hofeldts were APR lessees, RANGE’s 2012 story shows they weren’t fans of free-roaming bison, rather, vocal opponents.

Dustin Hofeldt recalls that the first lease he signed was just a “straight, regular lease with standard conditions for three years, nothing special.” But as the Hofeldts became active against APR, eventually reserve manager Bryce Christensen warned: “We needed to watch what we said, or we would lose our lease. But we kept right on going.”

The Hofeldts wound up selling that ranch, which Vicki explains was “way out of our way” in relation to two ranches they now have at Landusky and Cleveland north of the Missouri. The Nature Conservancy bought it because “we weren’t going to sell it to APR.” And the Hofeldts no longer lease APR graze.

How about Lee and Perri Jacobs, who shared East Dry Fork with the Hofeldts? Are they interested? Perri gave RANGE a copy of an APR solicitation-for-proposals letter, which gives a short version of the stipulations.

Besides a requirement for $1 million in “public liability insurance,” there are 11 major conditions, two of which are “standard,” relating to experience and fiscal capacity. Seven others require, for example, “a history of supporting environmental conservation efforts.” But two are real doozies: “Ideal Lessees…(2) are willing to enter into the Wild Sky Rancher program; [and] (3) will publicly support American Prairie Reserve goals and programs.”

Does the program have takers? Well, nobody is bragging—one thing most ranchers keep until the end is pride. Another thing ranchers treasure is predictability. Leah La Tray, who co-owns the Paradise Ranch north of Lewistown, has seen the prospectus letter. Even if she could tolerate the extortionate fees and the mandate to volunteer for APR’s public relations team, La Tray isn’t interested because “the leases rented out are temporary, just a short-term arrangement nobody can rely on.”

Perhaps APR prefers to sit on these leases, let them fallow. Trouble is, BLM grazing leases carry an expectation of utilization, not dormancy. In short, “use it or lose it.” As an example, in the 43 CFR 4130 grazing regulations, subsection 4 (e) (1) allows temporary nonuse, but “only if the authorized office approves in advance and (ii) For no longer than one year at a time.”

While APR may hope nobody notices, it’s too late. Lisa Darlington has: “APR doesn’t seem to think they need to follow the same rules as Joe Public.” Anna Morris pointedly asks: “What’s going to happen to these allotments if APR can’t fill them with bison? You can’t use them to graze wildlife.” Grass Range Angus rancher Joe Delaney, who sold his Lazy 4J property in 2018 only to learn later his buyer had flipped to APR, had expected to graze that ranch in 2019 and had paid his lease fee. But reserve staff insisted he sign its new standard form, with “stipulation after stipulation. We even had to call them prior to being on the property.” Delaney had “had enough,” returning only in spring 2019 to gather his equipment. “Nobody had been there; there were no fresh tracks at all.”

RANGE bounced across the old Frye holdings, trying to get a look at the Dry Fork firsthand. There was no sign of recent livestock or human presence. RANGE later told the Hofeldts and Dustin responds: “I spent my entire life managing grass. This range has to be grazed to stay vibrant or it becomes stagnant; all the species they’re worried about start dying off. These guys…they don’t know what they’re doing.”

Breaking Away

Turns out, the reserve is assiduously working on its answer to Anna Morris’ question. In November 2017, the reserve submitted a 66-page proposal, amended from a January 2017 proposal, to fully convert 18 grazing allotments to year-round buffalo graze: “APR is seeking permission to: change the class of livestock from cattle to bison; allow for season-long grazing; fortify existing external boundary fences by replacing the second strand from the top with an electrified wire; and remove interior fences.”

Further, APR asked that all its private property holdings, plus associated state leases, be unitized with each BLM grazing right into one unfenced year-round pasture. Then, after the units are “stocked with indigenous animals” as fast as bison can breed, APR asked that all 18 be wrapped into one tidy permit.

What herd size will APR have if its proposal is approved: 4,361 head, expected to take 12 to 14 years at Yellowstone’s 14 percent growth rate. At that point, about 650 head would need to be removed or sold to maintain herd size. Big enough to impress donors? The public? APR certainly hopes so.

This sweeping request for changes on 375,000 multiple-use public acres scattered across over 100 miles west to east triggered the National Environmental Policy Act process (NEPA), but APR seeks only the lower level of review in an Environmental Assessment (EA), usually reserved for minor changes on smaller acreages that result in a so-called FONSI, or Finding of No Significant Impact, either to the environment, economy, or affected community.

Why? Full Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) cost more, cover more issues, and take longer. However, APR was able to change the livestock class on two allotments it had bought early on (not without protest, however), so why not on 18?

Announced to the public in April of 2018, the EA underwent two months of scoping (public comments on the issues needing study). In December of 2018, the scoping summary was released, with lots and lots of issues raised. Since then, BLM has been very quiet regarding APR’s proposal, with the last active news release posted February 2019. However, plenty of noise came from elsewhere, specifically the Montana Legislature. But before discussing the political battle ignited by the APR conversion proposal, it’s worth taking a closer look at two of the 18 subject allotments and why an EIS is necessary and proper.

Two Crow

The Two Crow ranch, listed for just under $8 million, became APR’s first buy in far northern Petroleum County in the summer of 2017. It included 5,000 private plus 41,000 leased acres 30 miles north of Winnett.

The Two Crow is not listed as being available for lease in 2019, hinting that APR hopes to put bison on it quickly. Neither, for that matter, is the PN, nor is Timber Creek, 18,000 deeded/131,000 public lease acres in the Larb Hills of Valley County. That buy, from the Page family, “more than doubled” APR’s holdings in 2012.

Terry Holst, retired from 30 years as a rangeland management specialist, always from BLM’s Lewistown field office, worked directly on Two Crow multiple times over his career. The net result for Holst is the creation of world-class, world-famed bighorn and elk populations, plus excellent beef production numbers. The bighorns began with an in-state transplant, becoming a “source herd” of hundreds, so good that auction winners of Montana’s six-figure “governor’s permit” often choose to fill their spendy tag in the Two Crow region.

Then, in the Clinton era, Holst and others worked with Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and affected ranch owners to engineer integrated rest-rotation grazing for the Two Crow. It worked, “very successful at reducing prickly pear and increasing native bunchgrasses and green needle grass,” Holst recalls. “A world-class elk herd runs out there now, for which it took me 20 years to get a permit, for Unit 410 in North Petroleum.” Holst has been on the Two Crow during archery season, seeing “up to 100 camps one weekend.”

Two Crow also means cattle. Leah La Tray points out past beef production off Two Crow: 2,000 yearlings for market each year during the six-month grazing window. “That’s at $1,800 per head, or $3.6 million at the fall sale that flows through our state and local economy, gone, while APR brags about its total input into our economy of what was it, $8.6 million over four years, $2.15 million a year for everything versus one allotment? Do the math!”

Back to wildlife. As a sportsman and professional who spent a career helping both wildlife and livestock co-prosper, Holst has two main concerns. Over the years, he recalls domestic bison from a nearby private ranch that used their freedom to visit Two Crow: “Buffalo can, and do, crossbreed with available cattle.” Furthermore, like elk, deer and even cattle, the fugitive “buffalo were always where the good water was. They’re no easier on riparian areas than cattle.”

The other concern comes from Holst’s professional understanding of “conservation biology” and its emphasis on “keystone predators.” He fears once the bison are “free roaming,” and therefore free breeding, bringing in carnivores to “regulate” things comes next. Holst expects that will “crash game herds, just like wolves crashed deer and elk in western Montana. I see all this as going backwards, not forward.”

Dry Forked

Some 30 air miles across the Missouri from Two Crow is Dry Fork, in south Phillips County. The 19,000-acre Dry Fork is also famous among a select few for its prairie dog hunting, reachable from the Dry Fork road between U.S. 191 and the Regina/Sun Prairie area to the east. Grazing is on three large pastures shared in common between APR’s old Frye Ranch base property (which the Hofeldt cattle used to graze) and the Jacobs Ranch.

RANGE visited with Perri Jacobs, while husband, Lee, was ranching. It’s worth noting that Perri has a master’s in public administration—or master paperwork arranger. She had plenty of paper to share with RANGE, plus her commentary. One paper was extra special…the reserve’s proposal to split Dry Fork, changing the AUM shares as well.

The current allocation is 1,590 AUMs for APR and 1,077 for Jacobs, across all three pastures with one getting full rest each year. The proposal? APR gets 1,792 AUMs and two pastures, Jacobs Ranch, 862 AUMs on one pasture. Got that? Yep, the Jacobs Ranch gives up 212 AUMs.

“APR never came to us prior to making their proposal in the EA,” Perri recalls. “I heard about the scoping process in the news and went online. I was outraged that they would do this without the courtesy of talking to us first.”

Toward the end of May 2018, the Jacobses, including Lee’s dad, Francis, finally met with APR and BLM staff about East Dry Fork. Nothing changed, including the part in the original proposal reading, “If Jacobs are unwilling to split the allotment, another alternative is to run APR indigenous animals in common with Jacob’s [sic] cattle on the entire allotment.”

What’s this “indigenous animals” thing? Yep, supposedly applicable through federal regulation 43 CFR section 4130.6-4 according to a BLM footnote in the scoping report issued December 2018. “There are lots of rules for grazing livestock, but nothing about those rules being intended for grazing ‘indigenous animals,’” Jacobs declares. “Show me the law that says you can do this. Not the policy, but the federal statute, the law!”

The regulation apparently allows “authorizing grazing use by privately owned or controlled indigenous animals…at the discretion of the authorized officer

consistent with multiple-use objectives…not to exceed 10 years.” Ah, discretion. Got it. And of course, the buffs will be happy to stay behind that new electric wire.

Good Neighbors

In sum, Perri Jacobs observes: “For all their talk about being such great neighbors, that’s not very neighborly.”

One “talk” example, from a May 2018 Tri-State Livestock News opinion article by Betty Holder, a retired Forest Service district ranger turned APR reserve manager: “American Prairie Reserve works hard to be on good terms with our ranching neighbors,” and a bit further down, “[APR] takes being a good neighbor very seriously.”

Besides a lack of manners, APR is short on “truthiness,” too. In March of 2016, rumors began to fly that the reserve was buying the historic PN Ranch at Judith Landing north of Lewistown in Fergus County. At 21,000 acres deeded/27,000 public graze, listed for $21 million, PN was certainly a big step onto new ground for APR, with what looks like a $14 million mortgage.

Reserve outreach staffer Hilary Parker told media the rumors were untrue, with “a lot of misinformation out there.” Two months later, the PN became APR property, raising a lot of new, unfriendly eyebrows.

Unwilling Seller

Since its start, the reserve has taken pains to remind the world it will “stitch together” the reserve “using private lands purchased from willing sellers.” That seems to have changed somewhat. In summer 2017, APR bought the Two Crow discussed above. For Grass Range Angus ranchers Joe and LeAnne Delaney, the Two Crow sale was “handwriting on the wall.” Delaney decided to put his nearby “Henry’s Place” operation (aka Lazy 4J) up for sale. But not to APR.

“APR was the first caller after listing. I said no,” Joe recalls. When a third-party LLC offer came knocking, “I had my lawyer check the LLC’s agent out, and he said there was absolutely nothing he could find” connecting the agent to APR. The sale closed at the end of May 2018.

In December 2018, Joe’s phone rang. It was Betty Holder at APR. “Betty said, ‘We bought the Lazy 4J property. We thought we should be the first to let you know.’ I just felt sick.”

Delaney never did learn who actually backed the LLC, and the confidentiality clause he signed prevents him, or anyone else, from ever knowing. But again, more eyebrows in new places were raised.

Game Changer

Many whom RANGE visited mentioned various tricks played by APR, but their overall main concern is APR’s apparent change in strategy. Prior to the PN, APR’s efforts primarily focused on “core” centered on the Sun Prairie in sparsely populated Valley and Phillips counties north of the river, far to the east.

The PN is at least 50 air miles west of any other significant reserve holding, on the “wrong” south bank of the Missouri River, as is Two Crow. Neither match prior strategy. Further, as Dana Darlington knows firsthand, the PN is rough breaks and steep: “It’s not typical country where you would run buffalo. You can’t fence it efficiently.”

Suddenly, what “happens in Valley/Phillips stays in Valley/Phillips” no longer applied. “When APR bought the PN, that finally woke people up in Fergus County,” remarks a slightly droll Dustin Hofeldt. “We’re happy to have them on the team.”

Like many producers all across Montana, Laura Boyce and her husband, Dan, had been aware and concerned about events to the east, but not active. “Part of the Montana neighbor ethic is to mind your own business and help only when asked.” Through the PN buy, APR suddenly became a practically next-door neighbor just to the north, on the same side of the Judith River as the Boyce ranch atop Bear Springs Bench in Fergus County. The next year, the Two Crow put Petroleum County on APR’s map.

Critical Mass, Again

Overall, the unexpected expansion of APR’s ownership endpoints catalyzed an expanded, multilayered opposition politically from the conservation district and county level all the way up to the state legislature, and also at the individual, private level.

The Conservation Districts

In 2013, the Montana Association of Conservation Districts resolved that it was “opposed to free-roaming wild buffalo or bison.” It also called for legislation that would ensure that any buffalo “corralled, fenced in, or transported is no longer considered free-roaming and/or wild” and further be “defined as domestic livestock and subject to Montana laws.”

On the local level since, individual districts have had voters approve ordinances which in essence expand the threats against which “protection of water and soil” resources are required for “wild, free-roaming or domestic bison grazing.”

First out of the gate was McCone County (seat Circle) in 2012, which is across the Missouri from the Fort Peck reservation, cornering on Valley County. Valley County was next, in 2014, with Fergus, Phillips, and even far-away Carter (seat Ekalaka) voting in 2016, with the average approval for all at 69 percent. There are more to come.

The Counties

The Fergus County commissioners provided RANGE a copy of its Resolution 3-2016, approved in April of 2016, while the PN sale was still “misinformation.” Under the resolution, all bison in Fergus are now “domestic livestock,” with commission authorization required “before any buffalo/bison, not considered livestock, can be translocated in Fergus County by any entity.” Valley and Phillips counties passed similar resolutions earlier.

Perri Jacobs points out it’s not just bison: “The commissioners of the affected counties are communicating much more on common issues that affect maintaining the rural economy and way of life.” But there may be even closer working relationships on the menu. While too preliminary to discuss, a team of consultants from Kansas have been traveling around, holding discussions on how the counties could take better advantage of federal statutes and have a stronger hand when dealing with the federal government.

The Legislature

The Montana Legislature meets every other winter for four months, so sessions are jam packed.

There were three major legislative items concerning bison policy in 2019’s session. One was House Bill 132, sponsored by Ken Holmlund (R-Miles City), defining a wild bison as one that “has never been” owned, “reduced to captivity” or taxed as livestock. Gov. Steve Bullock (D), a candidate for president, demanded that “has never been” be amended to “is,” but that was rejected by the Legislature. Veto.

Another was House Bill 332, sponsored by Rep. Joshua Kassmier (R-Fort Benton), which took the county authorization concept in Fergus’ 3-2016 up a notch, requiring statewide “authorization by county commissioners…before wild bison are released” into any county, and only after strict quarantine protocols have been followed. Veto.

The last, but not least, was House Joint Resolution 28, sponsored by Dan Bartel (R-Lewistown) and 26 others. HJ 28 passed with big legislative margins like the others. But the governor can’t veto resolutions, which in this case was a nonbinding yet clear “sense of the Legislature” message “urging” the Bureau of Land Management to “deny the grazing proposal by the American Prairie Reserve” for the 18 allotments discussed above.

RANGE was told multiple times along the way how, during legislative hearings on HJ 28, after admitting: “We are under no illusions about the controversy of our project,” APR’s lobbyist complained. “You don’t have to like us, you just have to respect our property rights.”

Sponsor Dan Bartel winces, pauses and responds, “The resolution language reads ‘250,000 acres of public property.’” He then clarifies: “I would never attack private property rights. These leases cover grazing on public lands where the affected public has a right to a say.”

In her turn, LeAnne Delaney is less diplomatic: “They can do whatever the heck they want on deeded lands. Build a 10-foot steel wall for all I care, it’s their land, period. But public lands? Whole different deal.”

Bartel concludes: “When you’re seeking to change the landscape as much as APR wants, well, BLM should either deny the proposal, or put together a proper EIS. Everyone, especially the public, deserves to know up front what APR’s end game is before the grazing is changed, the fences get ripped out, and there’s, what, 4,360 bison roaming around?”

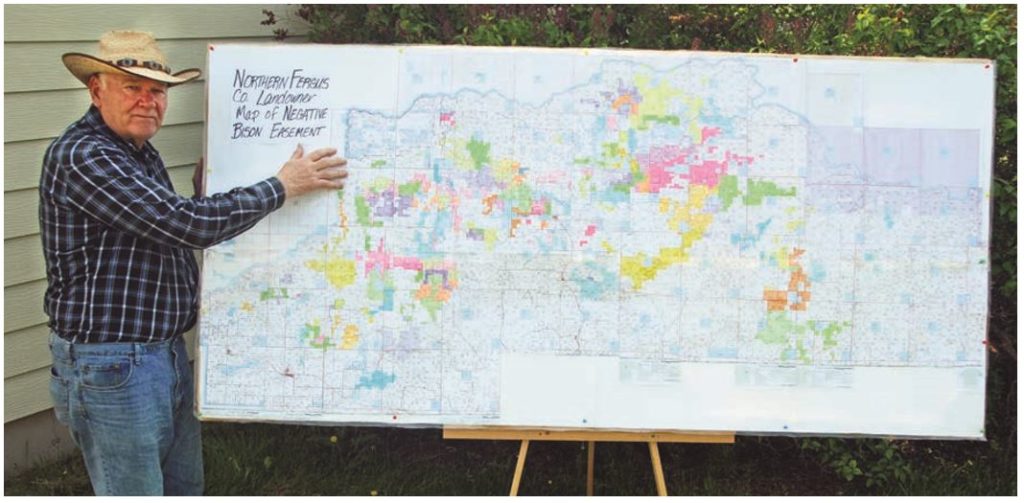

Proofing a Negative

Besides the legislative action, ranchers in Fergus County came up with a rather-direct, personal way to slow down APR. In late 2016, legal help was sought from law firms in Havre and Bozeman, and after consultations it was decided to record “negative easements” on the titles of private property if owners agreed. The easements prohibit the grazing of bison on recorded property.

Laura Boyce explains: “Zoning and/or covenants were not an option. Zoning requires a vote, and another vote can change everything. Covenants can be amended. We needed something that gave us the power to quickly do something for ourselves, among ourselves.”

While no money was involved in the easements, recording fees were two bucks a page, so separate recordings would be very expensive. But a master document would work. “We’re a community, sticking up for one another,” Laura explains, so it was decided that all the easements would go on one document. “No one could then be picked off singly. Further, all would have the same 20-year expiration/renewal date.”

How does that affect APR? Basically, the “time value” of money. No rational person would buy a new Cadillac if they couldn’t drive it for 20 years or had to let someone else drive it.

Why not 50, or permanent? “We’ve been around for generations, so we know families, circumstances and markets change. Twenty years means each generation stays involved, everyone acts together as a community.”

So, “by default,” Laura Boyce took the lead, arranging volunteer teams to do what was pure bureaucratic grunt paperwork. The most difficult part was the legal descriptions for each parcel. “One of us would be reading the legal description off the state cadastral site out loud, with another person typing it into the official document, another marking on a paper map, another proofing—and all of it had to be just right or it wasn’t legal,” she remembers.

In Fergus County, across the entire north half, 75 private ranch properties reaching across the upper arc of Fergus County west to east, 300,000 acres, have prohibitions against bison that run with the title. “If it hadn’t been for Laura taking this bull by the horns,” Ron Poertner states flatly, “it wouldn’t have gotten done. Period.”

Boyce sees the challenge now is for the other affected counties where APR is active (Petroleum, Choteau, Phillips and Valley) to organize and execute their own negative easements to protect themselves. “We’ve done it, we’re helping, they won’t have to reinvent the wheel. They’re now working on gathering the names and properties to be implemented by this winter [2019-20].”

There is some expectation the reserve will buy one of the easemented properties and immediately file a lawsuit to have all the restrictions thrown out, but that’s for when that day comes, if ever.

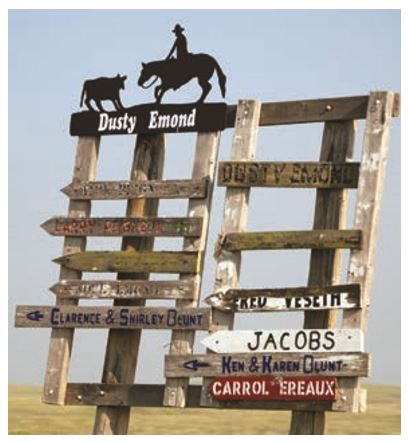

Signs of Resistance

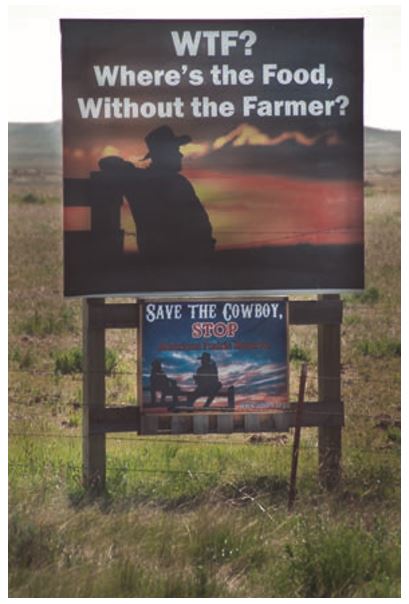

Finally, at the most individual level, there have always been signs of resistance to APR. As Bloomberg’s travel writer wrote in 2016: “Given the populist moment we’re in, it’s not surprising the reserve is controversial. ‘Don’t Buffalo Us’ signs stud a few roads leading in and out of reserve property.”

Since January, however, new signs have popped up everywhere in east-central Montana, reading: “Save The Cowboy. Stop American Prairie Reserve.” The banner campaign started small this winter, with one person’s donation check and one print shop. The simple slogan Save the Cowboy cuts to the chase, with undeniably broad appeal. Now, it’s a campaign under the umbrella of United Property Owners of Montana, which in turn is cooperating with all the involved existing pro-ranching groups. Under consideration is targeted fund-raising, for full-size billboards where available, as well as bringing back a version of the old Burma-Shave roadside jingles—four signs with Save the Cowboy at the end.

In any case, APR’s tour guides will need to get really good at making their few guests “Oh, look there!”—for hundreds of miles. They’ll also need to be taught really good answers for the inevitable question: “What do all these Save the Cowboy signs mean? I like cowboys!”

The Long Road Ahead

When RANGE hit the road for interviews, most everyone contacted along 1,500 miles expressed the sense that as long as American Prairie Reserve exists, it will be locked in a generational struggle against central Montana’s agricultural community.

“This is everybody’s fight, not just ranchers. There’s a growing realization that they don’t want any of us living out here at all,” observes Dana Darlington. “They want the Big Open, a Big Empty.”

Ron Poertner agrees: “When these guys are done, there probably won’t be a single building standing on the preserve.”

“I’m concerned for my community as a whole, because I understand the impacts on the economy APR could have if its vision becomes reality,” Leah La Tray explains. “I’m also really concerned for my kids. If we lose that much land from our economy, we’ll lose their future, not just mine. These businesses, these towns within the influence of the reserve could dry up faster than anyone can now guess.”

But APR is not a done deal by any objective measure. It is big, but nowhere near the “huge” it needs to be. Public documents show it falling short on all counts—acreage, funding, stocking, even niche sales. Reserve income only covers 10 percent of expenses, numbers normally posted when there’s a Silicon Valley tech meltdown. APR’s graze is fallow. Its facilities are either vacant, incomplete and/or behind schedule. Visitation and recruitment are insignificant, and those visitors who actually come have a heck of a time even finding bison. APR had to expensively rent Ken Burns to get donors to its previously bombing New York “galas.” (See “A Tremendous Honor,” page 22.)

On the other hand, counties and conservation districts are passing ordinances and resolutions to hinder APR at every opportunity. For the second time in as many sessions, the Montana Legislature passed bills that would have made it difficult, if not impossible, for any “free-roaming” herd to be established anywhere in Montana except on tribal lands. Only vetoes from term-limited governor and outlier Democratic presidential hopeful Steve Bullock “saved” APR.

Only if his party wins the open governorship will the vetoes continue. Hundreds of thousands of critical acres of private lands are already restricted against bison by negative easements, with perhaps millions more soon to follow.

What comes next? Who knows, but it will probably be pretty entertaining. “Sure, these billionaires can pour their money into their ‘legacy,’” LeAnne Delaney concedes. “But we pour our blood, tears, hearts and souls into ours. Really, which is more valuable?”

We’ll all find out, soon.

You may also like

-

Omnibus bill provision would “unleash” electronic tracking on nation’s cattle

-

Arizona rancher sues to stop million-acre national monument

-

Bob West: Facing the reality of wolves, Colorado ranchers need to be prepared

-

Protect The Harvest: The whole truth about Western ranching

-

Packing behemoth JBS aims to takeover world’s meat industry

Perhaps APR will take in a bunch of the government’s feral / wild horses.

The federal government might even Pay an outfit like APR to take wild horses in.

Seems like a match made in heaven .

APR will fail simply because it is a Supposed non profit.

We All Know that when the big money in apr formatted their tax play, they’re all claiming Conservation Easement and Likely at an Appraised Value.

Probably appraised at 4X the original money spent.

Anyway Montana will end up w a mess, the Feds will end up w apr Land….and down the road it will All be dissolved…some to the State and the Feds will keep some too.

Just be the future apr grazing and nature park. LoL.