Federal Land Settlement Policy in The Western United States With Emphasis on Federal Acquisition and Disposal of Land in The Malheur Lake Area of Harney County, Oregon

Federal Land Settlement Policy in The Western United States With Emphasis on Federal Acquisition and Disposal of Land in The Malheur Lake Area of Harney County, Oregon

Angus P McIntosh, PhD, Director Natural Resource Law & Policy Research, LAW USA Foundation

Michael S. Coffman, PhD, Environmental Perspectives Incorporated

September 11, 2016

Factual Background & Assumptions:

The current Malheur National Wildlife Refused is comprised of some 187,000+ acres of land, with very diverse ownership status and history. The original Refuge was set aside by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908, comprising just a small portion of the current claimed acreage. The Refuge has been vastly expanded since that time through a variety of means. United States v Otley, 127 F2d 988 (9th Cir 1942) makes it very clear that at the time that case was decided there were a wide variety of disputes regarding title to Refuge lands even as they existed at that time, including recognized adverse possession claims. This paper makes no attempt to examine all title issues applicable to the full acreage purportedly involved or included in the current refuge. The primary focus of this paper is on the Refuge headquarters and improvements located in the South half of Section 35, Township 26 South, Range 31, Willamette Meridian, and to some extent the adjoining Section 36, where the alleged adverse possession occupation occurred earlier this year. This paper recognizes factual and legal issues associated with title to both Section 35 and the adjoining Section 36, upon which some additional headquarters infrastructure, including a landing strip, is located, which property by Act of Congress should have been a state school section.

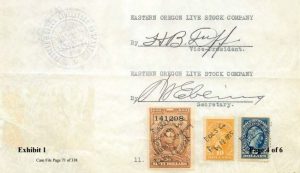

With respect to Section 35, however, according to the applicable chain of title, “the South East quarter of the South West quarter and the South half of the South East quarter of Section thirty-five in Township twenty-six South of Range thirty-one East of Willamette Meridian on Oregon” was conveyed the United States of America, Benjamin Harrison, President, to Charles Marion Harney, in a Land Patent dated September 1, 1890. (Book unk., Page 487). From that point until at least 1935, that land remained in private ownership  through a series of private property conveyances. The property was purportedly re-acquired by the United States Government via deed from the Eastern Oregon Live Stock Company, dated February 18, 1935. The area immediately north of the Refuge Headquarters (Township 26 South, Range 31 East (South of Malheur Lake), Willamette Meridian, Harney County, Oregon, section 35, lots 5 through 7 (part of Tract 19)), was reportedly purchased from Paul C. and Ruth Stewart as evidenced by Warranty Deed recorded November 27, 1940. It should be noted, however, that the copies of such deeds provided are not certified copies, and do not include clearly identifiable recording information, and; they are not self-authenticating documents. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that these documents are authentic. But for purposes of this paper, and applicable discussion and analysis, we assume that the documents are correct, and can be verified and authenticated.

through a series of private property conveyances. The property was purportedly re-acquired by the United States Government via deed from the Eastern Oregon Live Stock Company, dated February 18, 1935. The area immediately north of the Refuge Headquarters (Township 26 South, Range 31 East (South of Malheur Lake), Willamette Meridian, Harney County, Oregon, section 35, lots 5 through 7 (part of Tract 19)), was reportedly purchased from Paul C. and Ruth Stewart as evidenced by Warranty Deed recorded November 27, 1940. It should be noted, however, that the copies of such deeds provided are not certified copies, and do not include clearly identifiable recording information, and; they are not self-authenticating documents. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that these documents are authentic. But for purposes of this paper, and applicable discussion and analysis, we assume that the documents are correct, and can be verified and authenticated.

Analysis:

By way of general background, the principal reason for the dramatically different land settlement policy of Congress in the disposal of Western public lands (from the policy of limited acreage amounts followed in the East) was the dramatically different climate and terrain that exists West of the 100th Meridian. (California v United States, 438 US 645 (1978); United States v New Mexico, 438 US 696 (1978). Following the Mexican War, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848) and the Oregon-Northwest Treaty with Great Britain (1846) gave  the United States vast new lands for settlement. Under the Homestead Acts (12 Stat 392 as amended) a homesteader could acquire 160, 320, and eventually 640 acres of land. All the lands capable of supporting a farm or ranch family on these amounts were quickly settled and acquired under these limited acreage laws. The majority of the arid lands west of the 100th Meridian were settled and the public lands disposed of under the Desert Land Laws (19 Stat 377 as amended), related federal Water Rights and Easement Laws (14 Stat 253, 16 Stat 218, 29 Stat 484, 26 Stat 1095), and the Stock-Raising Homestead Laws (39 Stat 862 as amended). At the same time however, a significant amount of land in the West was already occupied and in the possession of Indian Tribes, former English citizens, and former Mexican citizens. Some of these people held perfected title documents from the former English and Mexican governments, some had inchoate titles, and some held only by the right of “possession” or “occupancy”. Congress and the Supreme Court had always recognized and respected “pioneer” rights of occupancy and possession and had always given a “preference” right to acquire the government’s legal title (or patent) to settlers in the actual occupancy and possession of the land.

the United States vast new lands for settlement. Under the Homestead Acts (12 Stat 392 as amended) a homesteader could acquire 160, 320, and eventually 640 acres of land. All the lands capable of supporting a farm or ranch family on these amounts were quickly settled and acquired under these limited acreage laws. The majority of the arid lands west of the 100th Meridian were settled and the public lands disposed of under the Desert Land Laws (19 Stat 377 as amended), related federal Water Rights and Easement Laws (14 Stat 253, 16 Stat 218, 29 Stat 484, 26 Stat 1095), and the Stock-Raising Homestead Laws (39 Stat 862 as amended). At the same time however, a significant amount of land in the West was already occupied and in the possession of Indian Tribes, former English citizens, and former Mexican citizens. Some of these people held perfected title documents from the former English and Mexican governments, some had inchoate titles, and some held only by the right of “possession” or “occupancy”. Congress and the Supreme Court had always recognized and respected “pioneer” rights of occupancy and possession and had always given a “preference” right to acquire the government’s legal title (or patent) to settlers in the actual occupancy and possession of the land.

There are many US Supreme Court decisions on the subject of how individuals acquire property rights of “possession”, “occupancy” or “use” through “settlement” and “improvement”. One Oregon case that specifically refers to these possessory rights as “pioneer rights” is Lamb v Davenport, 85 US 307 (1873). However, this concept of “possessory” property rights as an individual right (regardless of whether the individual was an Indian, Hispanic, Anglo, etc.) existed in the Western territories under the prior English, French or Mexican laws and customs (Sunol v Hepburn, 1 Cal. 254 (1850)). Regarding “stockraising” or “grazing” the US Supreme Court stated in Arguello v United States, 59 US 539 (1855), that a “cattle range” held in “possession” for 50 years (from prior to the Mexican cession to the US) was sufficient evidence of ownership. “Possessory” or “occupancy” rights of actual settlers typically have the sanction of State or Territorial legislation, or; local laws, customs and decisions of the courts; or “aboriginal title” or “possessory” or “occupancy” rights dating from a time prior to US acquisition through “treaty” (ie. Guadalupe-Hidalgo, 1848, or the Oregon-Northwest Treaty with Great Britain, 1846).

This same possessory or occupancy right of “actual settlers” gives the settler a “color of title” which has been referred to as the “preference” right. The preference is the preferred right to acquire the government’s “legal title” when the land occupied or in the possession and use of the pioneer is eventually opened to disposal. (See Frisbie v Whitney, 76 US 187 (1869)). This pioneer right of possession and preference gives the occupant the right to sell his improvements as well as his possessory right prior to acquiring the government’s “legal title”, and such ownership will “relate back” to the first pioneer’s date of settlement. This is important when establishing senior “water rights” and “land use rights” that predate later competing claims. The Supreme Court has held that this pioneer/possessory right or title is good against all the world, except the United States as the actual legal title owner. However, once the United States Congress by positive legislation recognizes, confirms, or sanctions a “use”, or grants a right or title, then it is no longer a mere preference or possession. Once recognized or granted by an Act of Congress, that right could not be defeated by an employee of the Executive Branch (i.e. Interior or Agriculture) who failed to perform their duty to survey and record the claim, (Shaw v Kellogg, 170 US 312 (1898), nor having been surveyed and recorded, could the grant be revoked by later administrative action Nobel v. Union River Logging R.R. Co., 147 US 165 (1893)).

Regarding stockraising by bona fide settlers on “public lands” prior to passage of the Grazing Act of March 3, 1875 (18 Stat 481), stockgrazing was merely at the sufferance or tacit consent “under an implied license” of Congress under a color of title based on State/Territorial “range” laws. While this “possessory/ preference” right was good against all others, it was not good against the United States as legal title owner until validated by, or properly initiated under, an Act of Congress (Frisbie v Whitney, 76 US 187 (1869) and The Yosemite Valley Case, 82 US 77 (1872)). However, after passage of the Grazing Act of 1875, Congress validated the right of settlers to “graze” cattle, horses and other stock animals (even to the point of “destroying grass and trees”), on any land open to settlement under the homestead, preemption, or mineral land laws. Of course it was often necessary to destroy trees in order to improve pasture, or to destroy grass in order to plant forage crops (Shiver v United States, 159 US 491 (1895); Stone v United States, 167 US 178 (1897)).

By the Act of July 26, 1866 (14 Stat 2530) Congress had already recognized, sanctioned and confirmed ranch settler’s stockwater rights (United States v New Mexico, 438 US 696 (1978)), and stocktrail (“highway”) right-of-ways (Curtin v Benson, 222 US 78 (1911)). Therefore, when land in the actual possession of a bona fide settler as a “range” was later incorporated into a federal military reservation, the ranch settler not only owned stockwater rights and stocktrail ROWs, but, had the “preference” right over all others to be “granted the privilege” to continue “grazing cattle, horses, sheep and other stock animals” following a determination that stockgrazing would not interfere with the military’s use of the reservation, (Act of 1884, 23 Stat 103). Here it is important to note that a Congressional “grant” could not be defeated by a bureaucrat’s failure to make a required determination (Shaw v Kellogg, supra). It must also be noted that a “privilege” is not a general “right” because it cannot be exercised by every citizen. A “privilege” is a “preferential right” that can only be exercised by a “preferred”, favored or exclusive class or group of citizens. In the case of the “grazing privilege” it could only be granted to the actual settlers in possession of the range who owned the water rights, range rights, easements, and improvements (forage, hay, fences, corrals, ditches, pipelines, wells, windmills, etc), (Atherton v Fowler, 96 US 513 (1877); Griffith v Godey, 131 US 89 (1885); United States v Krall, 174 US 385 (1899); Salina Stock Co. v Salina Creek Irr. Co., 163 US 109 (1896); (Wilson v Everett, 1891), Lonergan v Buford, 148 US 581 (1893); Swan Land & Cattle Co. v Frank, 148 US 603 (1893); Grayson v Lynch, 163 US 468 (1896); Ward v Sherman, 192 US 168 (1904); Bacon v Walker, 204 US 311 (1907); Bown v Walling, 204 US 320 (1907); Curtin v Benson, 222 US 78 (1911); Sellas v Kirk, 200 F2d 217 cert. denied 345 US 940 (1953); United State v New Mexico, 438 US 696 (1978)). Additionally, when the reservation was no longer needed for government purposes, any actual settler still in possession had the preference right to acquire legal title through the homestead laws or by purchase (Act of 1884, supra).

A short list of key decisions pertaining to this principle of “preference/possessory rights” related to “range” rights would be:

Arguello v US, 59 US 539 (1855), 50 yrs possession of a cattle range under color of title gives a title good as against the United States government.

Frisbie v Whitney, 76 US 187 (1869), Possession and improvement gives a settler a preference right to acquire title, which right land department officers are bound to protect.

Lamb v Davenport, 85 US 307 (1872), Possessory rights and improvements could be sold even before any act of Congress was passed allowing for disposal of that land.

Atherton v Fowler, 96 US 513 (1877), Possession of an enclosed range and improvement of the forage was sufficient to establish possession and defeat later homestead claimants even if the enclosed land far exceeded the amount allowed under the homestead laws. The first settler was entitled to compensation as owner of the forage cut and removed by a second fraudulent claimant even if the legal title to the underlying land was still in the US.

Hosmer v Wallace, 97 US 575 (1879), Where a settler was in possession or occupancy of thousands of acres as a stock ranch the land was segregated from appropriation by later settlers.

Griffith v Godey,113 US 89 (1885), A settler in possession of thousands of acres of a cattle range, controlled by his ownership of water rights in key springs and of a homestead was the owner of a property right in the range.

Wilson v. Everett, 139 US 616 (1891), An expansive cattle range on the Republican river and its tributaries covering portions of Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas was a possessory private property interest subject to recovery of damages.

Cameron v United States, 148 US 301 (1893), Possession and improvement of thousands of acres as a cattle range gave color of title or a claim that removed the land from the class of “public lands” and therefore the enclosure of such was not a violation of the Unlawful Occupancy Act of 1885.

Lonergan v. Buford, 148 US 581 (1893), An expansive cattle range together with all water rights, fences and improvements thereon covering portions of Utah and Idaho was possessory private property capable of sale and subject to contract enforcement.

Swan Land and Cattle Co. v Frank, 148 US 603 (1893), A large cattle range in Wyoming together with water rights, and improvements were possessory property rights subject to actions at law for recovery.

Catholic Bishop v Gibbon, 158 US 155 (1895), By treaty possessory rights of settlers in British Oregon shall be respected.

Grayson v Lynch, 163 US 468 (1896), A cattle range suitable for pasturage, watering, and raising cattle in New Mexico was a property right such that the owner could recover for damages caused by diseased cattle being driven across his range.

Tarpey v Madsen, 178 US 215 (1900), Possession implies improvement and settlement with intent to acquire title when land is opened for disposal, but cabins, corrals, improvements for hunting, trapping, etc also allowed.

Ward v Sherman, 192 U.S.168 (1904), A large cattle range, cattle then on the range, and the desert wells were all private property subject to sale and mortgage.

Bacon v Walker, 204 US 311 & Bown v Walling, 204 US 320 (1907)

Idaho range laws recognizing settler’s right to exclusively graze lands within two miles of their homestead did not infringe on United States’ underlying title.

St Paul M&M R Co v Donohue, 210 US 21 (1908), All public lands were opened to settlement and entry after 1880 and a settler’s improvements were sufficient notice of his claim to defeat later claimants.

Northern Pacific R Co v Trodick, 221 US 208 (1911), Until a local land office was established and a survey conducted the rights of settlers in possession of public lands could not be defeated by either subsequent withdrawal or grants to third parties.

Curtin v Benson, 222 US 78 (1911), Where a settler owned seven scattered parcels of land connected with 1866 Act right-of-ways, intermingled with 23,000 acres of range rights, before the United States included that land into a national park, the possessory range owner did not afterwards have to acquire a permit prior to using his property rights.

Under the Forest Reserve/Homestead Acts of 1891/1897 (26 Stat 1102/30 Stat 33) all land withdrawn as Forest Reserves that was occupied by “actual settlers” (possessory range rights), and was valuable for “agriculture” (stockraising), not only had “preference” rights attached to them, but also owned “property” in the form of easements, water rights, Right Of Ways, forage crops, timber use rights, and improvements that belonged to the bona fide settlers (Act of July 26, 1866 (14 Stat 253); Mining Act of 1872 (17 Stat 91); Livestock Reservoir Site Act, of 1897 (29 Stat 484), and cases cited above). The Act of 1880 (21 Stat 141) had opened all the land in the West to settlement, and had recognized that settlers’ improvements and possession were sufficient to put any later claimants on notice that the land was already occupied (Cox v Hart, 260 US 427 (1922). The Free Homestead Act of 1900 (31 Stat. 179) opened all agricultural public lands acquired by treaty to settlement and entry free of charge (except for filing fees).

In 1902 Congress enacted the Reclamation Act (32 Stat 388), which altered the policy of granting specific acreage amounts of Desert Land (i.e.160, 320, 640, etc.) and adopted the “Unit policy” which instead granted to a homestead entryman an “amount of land sufficient for the support of a family”. The same policy was followed when Congress enacted the Forest Homestead Act of June 11,1906 (34 Stat. 233, 35 Stat. 554) which included a “preference” right for actual settlers to enter any number of 160 acre tracts up to the amount of their actual settlement. In 1910, Congress authorized the granting of “allotments” to Indians “occupying, living on, or having improvements on” land within National Forests “more valuable for agricultural or grazing purposes than for timber” (36 Stat 863). In 1912 and 1913 Congress “directed and required” the Secretary of Agriculture to classify and open to entry and settlement all land within National Forests (37 Stat 287 & 842).

This was the law as it existed in 1912 when Congress amended the 1880 Act For Relief of Settlers (37 Stat. 267) and recognized a “preference right” of settlers to an “additional entry” under the “enlarged homestead provisions” of the Desert Land Laws to claim an amount of land to the extent of their occupancy and possession as long as their boundaries were plainly marked. By the end of 1914 all land in National Forests had been classified and designated as “grazing allotments”. The Desert Land Act Amendment of July 17, 1914 (38 Stat 509), and the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916 (39 Stat 862), were the culmination of the change in Congressional policy that created a split-estate that divided the surface agricultural and grazing values from the mineral estate and “merchantable timber”, (Kinney-Coastal Oil Co. v Kieffer, 277 US 488 (1928); and Watt v Western Nuclear Inc., 462 US 36 (1983)).

In 1916 (after 17 years of debate) Congress finally passed the only homestead Act specific to livestock production, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act. The intent of the SRHA was to make a permanent disposal of all the remaining approximately 600 million acres in the West “chiefly valuable for grazing and raising forage crops” (Stock-Raising Homesteads, 1916. House Rep. No.35. 64Th Cong., 1st Sess.). Section 10 of the SRHA provided for the withdrawal of 600 million acres under the 1910, Pickett Act for “classification” so the range could be surveyed, and allotted as “preferential” “additional entries” under Section 8 of the SRHA. Under the “unit policy” of the Reclamation law, once an entryman had paid the required fees, made the required improvement and cultivation, and the size of the unit was determined and the plat returned, the entryman had done all required and the equitable title was vested in the entryman (Irwin v. Wright, 258 US 215 (1922)). Amendments to the SRHA in 1919 required that stockraisers make an “additional entry” of all land “valuable for grazing and raising forage crops” within 20 miles of their original entry upon which they had improvements (41 Stat 287).

By an Act for the Relief of Settlers of March 4, 1923 (42 Stat 1445) Congress allowed settlers under previous homestead acts to convert their “original” or base property entries to either Desert Land (Enlarged) Homestead entries or to Stock-Raising Homestead Act entries in order to change their required “proofs” to $1.25/acre “improvements”. See also the Act of June 6, 1924 amending the SRHA (43 Stat 469). Both the Desert Land (Enlarged) Homestead Acts and the Stock-Raising Homestead Act also allowed “preferential” or “preference” right “additional entries” to the extent of the settler’s actual possession (where his boundaries were clearly marked), of an amount of land “sufficient for the support of a family”.

The Pickett Act (in conformance with Section 10 of the SRHA) and the Act of March 4, 1927 (44 Stat 1453) provided authority for the creation of Grazing Districts outside of National Forests, and the President began creating Grazing Districts in 1928. The Taylor Grazing Act (48 Stat 1269) provided for administration of Grazing Districts and provided a formalized process for establishing them. The TGA did not affect valid existing rights, and allowed for ranchers to complete their improvement requirements under section 8 of the SRHA. The TGA provided that the livestock numbers could not be reduced if the “grazing unit” was pledged as collateral for any loan. The TGA makes numerous references to “grazing rights”, “range”, “grazing privileges”, and ”preference rights”. The Act to Conserve and Develop Indian Lands and Resources of 1934 (48 Stat 984) also references valid rights, surface rights, and water rights of allotment owners. The Act also refers to “range units”, and “full utilization of the range”. The Act of June 26, 1936 amended the TGA and opened all Grazing Districts for disposal giving a preference right to permit holders (49 Stat 1976).

Beginning with the Act of March 3, 1933 (48 Stat 22), Congress enacted a series of statutes to buy failing, or abandoned farms (typically 160, or 320 acre homesteads), and then “resettle” them in “farm management units of a size sufficient for the support of a family” (Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act BJFTA July 22, 1937, 50 Stat 522). This was a continuation of the “Unit Policy” adopted by Congress beginning with Section 3 of the Reclamation Act of 1902 (32 Stat 388). The Act of March 3, 1933 (48 Stat 22) is the Act referred to in United States v Otley, 127 F2d 988 (9th Cir 1942), as the authority for the United States to acquire by condemnation the lands of the ranchers within the Malheur Bird Reserve. This was all in response to the Great Depression and Dust Bowl. This was an era of failing and abandoned farms, bankrupt counties due to no tax revenue, high unemployment, and failing banks due to defaulted farm and ranch loans. Congress passed a number of laws (48 Stat 22, 49 Stat 163, 49 Stat 1148, 49 Stat 2035, 50 Stat 8690) to create make-work conservation projects and buy up failed or abandoned farms in order to “resettle” the land under the Stock-Raising Homestead Act in conjunction with the BJFTA as “ranch units”, or to add the purchased lands to “Grazing Districts” established under the Taylor Grazing Act (48 Stat 1269). This land would no longer be plowed, but would be reclassified as “land chiefly valuable for grazing and raising forage crops”. Although Congress required that a minimum 3/4th interests in the minerals be retained by the United States, the whole idea behind these Acts was simply to “resettle” the surface estate or build conservation “projects”.

Congress wanted to make it clear there was no intention to acquire any jurisdiction over the land. So, it enacted the “Act to Waive Exclusive Jurisdiction” of June 29, 1936 (49 Stat 2035) : “That the acquisition by the United States of any real property heretofore or hereafter acquired for any resettlement project or any rural-rehabilitation project for resettlement purposes heretofore or hereafter constructed with funds allotted or transferred to the Resettlement Administration pursuant to the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act of 1935, or any other law, shall not be held to deprive any State or political subdivision thereof of its civil and criminal jurisdiction in and over such property, or to impair the civil rights under the local law of the tenants or inhabitants on such property; and insofar as any such jurisdiction has been taken away from any such State or subdivision, or any such rights have been impaired, jurisdiction over any such property is hereby ceded back to such State or subdivision.”

The classification, adjudication and surveying of “additional entry” grazing allotments was accomplished between 1923 and 1950. The Stock-Raising Homestead Act was the grant from Congress. Thus, the survey of the ranges into allotments, the recording of the maps, possession by stockgrazing for 3 out of 5 years, improvement of the additional entry to an amount equal to $1.25 per acre, and return of the maps to the ranchers in possession was all that was required by the statute, (see Sellas v Kirk, 200F.2d 217 cert. Denied 345 US 940 (1953).

Some people believe that the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976 somehow changed 130 years of Congressional grants and property rights. FLPMA itself contains 2 pages of “savings provisions” under Title VII intended to grandfather in place all prior existing rights. FLPMA specifically states “All actions by the Secretary [of Interior] concerned under this Act are subject to valid existing rights”. Congress the next year provided for the protection of ranchers’ property rights under the Surface Mining Reclamation Act of 1977. (91 Stat. 524, Sec. 714, 715 and 717). In 1983 the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Stock-Raising Homestead Act was intended to grant the surface estate to ranchers while retaining the mineral estate and ‘merchantable timber” to the United States (Watt v Western Nuclear, 462 US 36 (1983)). This had been the policy of Congress since the early 1900s, see also Kinney Coastal Oil v. Kieffer, 277 US 488 (1928). Also, see Stock-Raising Homesteads. 1916. House Rep. No. 35, 64th Cong., 1st Sess.

Conclusion:

Although Congress provided for the purchase of land to be included within Bird Sanctuaries by the Act of February 18, 1929 (45 Stat 1222), this could only be done with the consent of the State legislature (United States v New Mexico, supra). This is based on Article One, sec 8, cls 17 of the United States Constitution which states: “to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings…”

It should also be noted that the statute cited in United States v Otley, supra, as authority (48 Stat 22) for purchasing or renting land (Malhuer condemnation case) contained an exemption from an Attorney General’s opinion (Sec 355 R.S.) as per Article One sec 8 cls 17 for the specific reason that the government was only purchasing or renting the land temporarily for the purpose of “resettlement” or conservation projects. These acts were passed during the Depression/Dustbowl era and were never intended to create federal enclaves or assert any federal jurisdiction. Therefore, even if the purchase was legal there was clearly intent to dispose of the land and not to acquire any jurisdiction at all.

The land claimed to have been purchased by the United States from the prior owners (inclusive of Section 35) was acquired for “resettlement” or construction of conservation projects only. It was part of over 7,000 acres of land and 150,000 acre/ft. of water rights. It was included into the local Grazing District and adjudicated into Grazing Allotments in the 1940s. It was grazed and hayed as part of local “ranch units” for the next 40 years until the ranchers were purposely flooded out in the 1980s. They were forced to leave without compensation for their allotments, forage crops, improvements, stock-water rights, or the value of the land for grazing. Once those allotments were made they could not be reduced or changed (Sellas v Kirk, supra). Assuming the 1940s purchase of the land was legitimately done under 48 Stat 22, then the owners of those Allotments abandoned private property when they left in the 1980s. The surface limited fee Grazing Allotment being a completely separate estate from the United States mineral estate, those Allotments were then available for adverse possession. See (Kinney Coastal Oil v Kieffer, supra; Watt v Western Nuclear, supra). Since the United States cannot acquire property by adverse possession (Leo Sheep Co. v United States, 440 US 668 (1979)), then the surface fee Grazing Allotment could only be acquired by condemnation with consent of the State Legislature.

The 7,000 + acres of land and 150,000 acre/ft of water rights is an amount based on the Declaration of Charles Houghten, Regional Realty Officer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, dated September 9, 2016 the Refuge Headquarters (Township 26 South, Range 31 East (South of Malheur Lake), Willamette Meridian, Harney County, Oregon, section 35, lots 2 through 4, Sl/2 SEl/4 (part of Tract 46)). This land was purchased from the Eastern Oregon Land and Livestock Company on February 21, 1935. The area immediately north of the Refuge Headquarters (Township 26 South, Range 31 East (South of Malheur Lake), Willamette Meridian, Harney County, Oregon, section 35, lots 5 through 7 (part of Tract 19)), was purchased from Paul C. and Ruth Stewart via Warranty Deed recorded November 27, 1940.

Although these deeds appear to be registered in Harney County, certified copies have not been provided, and the documents are not self-authenticating. More importantly, there is no evidence in the record that the State of Oregon actually gave consent for these purchases as required by Article One, sec 8, cls 17 of the United States Constitution. Unless said consent is presented in evidence, the deeds are null and void and the lands are subject to adverse possession as if the transactions never occurred.

Finally, Congress waived any jurisdiction over the property by the Act of 1936, (40 Stat 2035) which states: “That the acquisition by the United States of any real property heretofore or hereafter acquired for any resettlement project or any rural-rehabilitation project for resettlement purposes heretofore or hereafter constructed with funds allotted or transferred to the Resettlement Administration pursuant to the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, or any other law, shall not be held to deprive any State or political subdivision thereof of its civil and criminal jurisdiction in and over such property, or to impair the civil rights under the local law of the tenants or inhabitants on such property; and insofar as any such jurisdiction has been taken away from any such State or subdivision, or any such rights have been impaired, jurisdiction over any such property is hereby ceded back to such State or subdivision.” It is clear that the Grazing Allotments were available for acquisition by adverse possession under state law and the District Court has no jurisdiction in this case.

You may also like

-

Arizona rancher sues to stop million-acre national monument

-

VDH: How to Destroy the American Legal System

-

Protect The Harvest: The whole truth about Western ranching

-

Colorado conservation group sues wildlife officials for skirting NEPA to get wolves into the state

-

Polis adds another radical activist to Colorado Parks & Wildlife Commission

true or fiction has all the national parks been turned over to the u.n. but the u.s. is still paying for upkeep and repairs for roads,etc????? i would like to have answers on this among other things. i am tired of all the secret deals ..

Debunked. Pwned. Jail time.

http://www.co.harney.or.us/PDF_Files/County%20Court/public%20land%20issues/Federal%20Ownership%20of%20Public%20Lands.pdf

You need to read both papers more carefully. They take apples and oranges approaches. Smith is in theory land talking in generalities. McIntosh & Coffman are talking applied theory, addressing specific title issues regarding a specific piece of proeprty under applicable Congressional Acts. Smith doesn’t even address what they’re talking about. Smith doesn’t debunk anything on this specific issue. She doesn’t even talk about this specific issue.

In 1988, I purchased 80 acres from BLM in Laughlin NV, under the Desert Land Entries Act of Congress. Over the decades, dirty harry & his BLM have been trying to transfer (extort) my land into certain corporations, adverse to my Title that I recorded with the Clark County Recorder on 9/20/1993. After years of fed courts dismissing jurisdiction to enforce my Title confirmation rights, my “valid & existing” Title rights are now in NV State Courts, against BWD corporations, where BLM or USA are not party because they no longer claim any interest in my Estate, after the USA granted BWD a “void” patent on my land, adverse to my 1st Title.

Can’t argue with the truth. Especially when it’s law. Superb.

Yes, I’m certain that the case will be thrown out because of this. And the Bundys will all be acquitted, because that’s clearly Heavenly Father’s will.

A Message for the Bundy’s and those that Stood in the Gap.

“Without Jurisdiction, The Charges Are Fiction!”

I have said this all along. side note:(Poor ‘Amanda Blankenship’, you lose)

God is good!

Lol touché